A Meteorite From the Moon

In 1982, the idea that a chunk of rock could be hurled from the moon to Earth by a lunar impact was considered pretty far out. For one thing, wouldn’t such a massive, high-energy explosion destroy the evidence by turning the excavated rocks to glass? Besides, meteorites were well known to come from…

In 1982, the idea that a chunk of rock could be hurled from the moon to Earth by a lunar impact was considered pretty far out. For one thing, wouldn't such a massive, high-energy explosion destroy the evidence by turning the excavated rocks to glass? Besides, meteorites were well known to come from small bodies like asteroids.

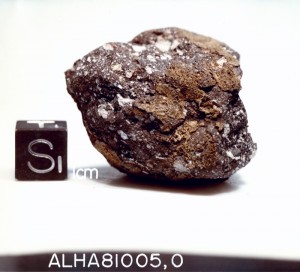

On January 18 of that year, a pair of geologists hunting for meteorites on the icy ground in Antarctica's Allan Hills region came across a greenish-tan sample they tagged as ALHA81005. It was the last stone they found that day before returning to camp—in fact, the last one of 373 specimens collected during the 1981-82 field season.

Back in the lab at NASA's Johnson Space Center, scientists immediately recognized the rock as unusual. When a thin section was sent to the Smithsonian's Brian Mason, an internationally known expert on lunar geochemistry, he commented in a scientific bulletin: "Some of the clasts resemble the anorthositic clasts described from lunar rocks." Mason, who died last week at the age of 92, was the first to make a connection between a meteorite found on Earth and the samples returned by the Apollo astronauts a decade earlier.

Later analysis confirmed Mason's suspicion. The types of glass particles in the meteorite matched those in lunar rocks exactly, as did the ratios of iron and manganese. Impact experts even came up with an explanation for how ALHA81005 got here in one piece. It turns out that rocks lying close to the moon's surface would be spared the worst shock effects in an impact. In fact, the lunar meteorite was no more damaged than other rocks Apollo astronauts had picked off the ground, even though it blasted off the moon at a speed exceeding 1.5 miles per second (lunar escape velocity).

When scientists presented these and other results at a conference more than a year later, "No one in the large crowd even stood to object to the provocative claim," according to Science magazine. "The psychological barrier to the idea that meteorites can originate on large bodies had been broken."