A New Time-to-Climb Record

A Yak 3U gets to 10,000 feet in 125 seconds.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Time-to-Climb-SteadFast-FLASH.jpg)

Will Whiteside has big plans for his Yak-3U racer SteadFast, and most involve setting world records. He and his team bagged the first record last October when he flew the Yak at 416 mph over a three-kilometer course (airspacemag.com/fastyak), beating a replica Hughes H-1 racer that had held the record since 2002. Today Whiteside is shooting for the records in time to climb to 3,000 and 6,000 meters—approximately 10,000 and 20,000 feet. His team has had an early breakfast a couple miles from the airport at the Kaffe Mocha and Grill, where they gather on appointed mornings, always in the same corner. Now they’ve assembled at Santa Rosa’s Charles M. Schulz-Sonoma County Airport (it’s named after the “Peanuts” cartoonist) in California, where SteadFast is hangared.

Whiteside, 41, flew for an airline for a while and now pilots for two Sonoma-area families who each own a half share in a very civilized turboprop twin. But he caught the racing bug early. First it was motorcycles, then, in 2005 at the national air races in Reno, Nevada, he started competing in a small sportplane, a Glasair III. The following year, Whiteside began racing the Yak—in the Unlimited class, for aircraft weighing more than 4,500 pounds. The class is dominated by World War II-era warbirds, and, although Whiteside has continued to lead the SteadFast racing team, since 2008, he’s been flying a heavier and faster Unlimited, the P-51 Mustang Voodoo, owned by California businessman Bob Button. In Voodoo, Whiteside was stalking Unlimited Gold, but the Mustang probably won’t make an appearance this September. Button has it up for sale. Last year, an accident causing 11 fatalities put the entire event at risk, but it looks like the Reno races will go ahead this year, and, if everything goes according to Whiteside’s plans, he’ll be there with the Yak and a fistful of world records.

This particular Yak came from Eddie Andreini, another Californian who flies Yaks and other warbirds in airshows. It’s been completely rebuilt, as all the crew members explain with some pride. When it was assembled in Romania in 2005 by Avioane, ostensibly as a trainer, it became the last factory-built propeller-driven Russian aircraft with a history as a fighter, according to Whiteside. And also, to hear this team tell it, one of the worst built.

Chris Seppler is a tall, lanky guy with an easy grin, a mane of silver hair, and a matching Vandyke who joined the crew after meeting Whiteside at the Santa Rosa hangar a couple of years ago. “The airplane was a mess,” Seppler says. “The wings had been assembled badly and were completely out of alignment, so they were completely rebuilt, the brakes modernized [at the factory, from pneumatic to hydraulic], and a new canopy installed. It’s like a completely different airplane.”

The team also added an injection system that shoots a 50-50 methanol-and-water mix into the cylinders when the engine is running at high power settings. Designed by engineer Pete Law, the anti-detonation injection, or ADI, system prevents the fuel-air mixture in each cylinder from detonating before the spark plug ignites it. If that were to happen, there would be a huge spike of heat and a sound known as engine knock, and after too much of that, the engine would fail.

Whiteside estimates that the ADI system gives him 300 or more additional horsepower. Without an ADI system cooling the cylinders, the engine would rely more heavily on fuel for cooling, and the team would have to run 20 percent more fuel in the fuel-air mix. More fuel in the mix impairs engine performance; leaning the mixture improves it, but leaves the engine vulnerable to excess heat. And that’s what the ADI system corrects: The methanol burns up, and the water vaporizes, taking heat with it.

Getting an airplane in shape to chase a world record is different from tuning one to race around a course at close to 500 mph, but Whiteside is driven to do both for the same reason. “The team is number one—by far,” he says. “Just to be able to have all these different personalities come out. Each one has his own specialty. We have introverts and extroverts, and [my role is] just to keep it going in a direction and try to keep everybody happy.”

There’s no apparent hierarchy in this team, but one man is The Man: Whiteside. If he says he wants something taken care of, he means you, the nearest crew member—Take care of it—and you do. And every member of the crew seems to know all the tasks it takes to support an aircraft at this level, so the final effect is like watching a defensive backfield shift to adjust during a football game.

The first chore of this late-February morning, as the doors slide away and the hangar yawns open, is an absolute imperative for record attempts: to weigh the airplane precisely with a calibrated and certified set of scales. Pilots can compete for recognition by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) and its U.S. representative, the National Aeronautic Association, in 23 weight classes, ranging from under 300 kilograms (about 600 pounds) to over 500,000 kilograms. Whiteside is aiming at two: He can do this because the Yak’s empty weight, about 5,300 pounds (2,400 kilograms), puts it astride a boundary between two weight classes: the first, aircraft weighing 1,750 to 3,000 kilograms, and the second, 3,000 to 6,000 kilograms. Fill all the tanks and maybe even add some ballast, and they can meet the requirement to weigh 50 pounds more than the minimum weight in the heavier category.

The team has a set of digital scales designed to be placed under an airplane’s landing gear tires—two under the mains and a third for the tailwheel. To get the Yak’s three wheels up and centered on the platforms, the team attaches the airplane’s towing fixture to a heavy pickup truck. The trick is to know where to place the scales so that when the truck moves the airplane, all three wheels will roll the same distance and arrive at the right spot at the same time. So out come measuring tapes as the crew members spot the small square platforms and ramps. They don’t get it on the first try, and it takes a couple of back-and-forths before the airplane is in position.

Hovering over the scales is NAA observer Brian Utley, a former IBM exec and an accomplished observer who will use a GPS-based data-collection system to monitor the aircraft during the attempt. On the roof of his rental car is a housing with a dome atop it that comprises the antenna for the telemetry from sensors installed aboard SteadFast. Utley, who looks like he could play a family doctor on TV, is as genial as he is meticulous about his work, and he photographs the scale’s readout to form part of the record paperwork. He’s decked out in his official neon-green observer’s tunic with “NAA” embroidered on it.

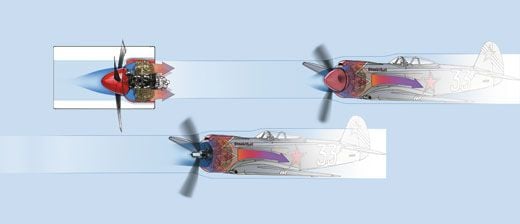

Among the many mods made to give SteadFast a higher top speed was a large spinner that nearly covers the airplane’s cowl where cooling air enters to absorb the heat from the fins surrounding the 14 cylinders of the Pratt & Whitney R-2000. The gap between spinner and cowl is less than an inch. Where did they get the spinner? From a Douglas A-26 Invader, a twin-engine light bomber, which rolled out a few years before the Yak-3, and is a much bigger airplane. The advantage it conferred in cooling the engine of the racing airplane turns into a disadvantage in a climb, so the spinner has been removed (see “Two Schools for Cool.”)

Now it’s late morning and there’s nothing left to do but fly. The noisy electric fuel pump grinds away, and some gas splashes onto the ramp. With the battery cart plugged in, the starter engages, and the prop struggles through a dozen revolutions with only one chuff and a puff of white smoke. The R-2000 finally catches and fires. Whiteside lets it warm up for a few minutes, then adds just enough power to break friction and get rolling toward Runway 32. The Yak waddles along on its wide main gear, its nose tilted up.

He runs his pre-takeoff checklist out on an apron adjacent to the runway, then taxis into position. The instant it starts its roll, Utley starts his clock. Whiteside accelerates gently until he has enough aerodynamic rudder force to manage the engine’s torque and the asymmetric thrust from the up-tilted propeller. In not much more than 15 seconds, he’s airborne and tucking the wheels up. He won’t pull up to his climb speed until the airspeed indicator pointer hits 160 knots, then he’s gone, clawing 1,000 feet upward every 10 or 11 seconds.

Although the time-to-climb record is a sporting affair today, in its execution it is remindful of Royal Air Force missions during World War II, when German formations crossed the English Channel to bomb strategic targets. Britain’s Hurricanes and Spitfires could wait on the ground for warning of an impending raid, then scramble and climb like their tails were on fire. High-octane fuel combined with engine power made that defensive tactic possible. On the other front, the Yak-3 was valued for its lightness, maneuverability, and sweet handling, and though its operational history on the eastern front against the Luftwaffe was predominantly at lower altitudes, it could out-fly—and out-climb—anything the Germans threw up against it.

The original Russian-built fighter entered service with a liquid-cooled V-12 engine, a Klimov, which is similar in layout to the U.S. Allison. Some Yak-3s have in recent years been manufactured to meet orders from warbird buyers in Germany, Australia, and the United States, who value the replicas, which are powered by Allisons.

After about 15 minutes, here comes the Yak on downwind, really moving. It rolls into a steep bank and Whiteside pulls up in a victory climb—though he doesn’t know the results yet. A few minutes later, with the aircraft chocked and the crew examining the remarkably clean belly—hardly any oil down there; a bolt-tightening session in the engine room paid off—a somber Brian Utley whispers something Whiteside was not expecting. A computer chip was missing from the airplane’s system; part of the data was not collected.

Some guys might have exploded in frustration, but not Whiteside. He’s just grinning. Well I guess that just means I get to go do this again! And that’s what happens. The volunteer crew turns to, adds fuel—plus some oxygen this time; it’s a requirement above 14,000 feet—and replenishes the ADI fluid. In the meantime, because part of the flight will be in controlled airspace above Flight Level 180, or 18,000 feet, Whiteside has to file a flight plan with air traffic control. There’s a lot going on at once, but this time, the routine of getting the airplane up onto the scales goes quickly and smoothly and by mid-afternoon, SteadFast is ready to take off again—this time with the computer chip in place.

On the following day, friends, family, and sponsors are invited to be present while the Yak makes a repeat run at the 3,000-meter record at an even lighter weight. On his previous flights, Whiteside had handily shredded the 3,000-meter record on the way up to 6,000 meters. Without the additional fuel needed to reach 6,000, he can gain a few seconds. He knows the airplane can do better, and it does.

Air temperature and other variables can affect climb rate, so no two flights are the same. Yesterday, Whiteside recorded a time of 2:24 to 3,000 meters in weight category D, beating the existing record of 3:33 set in 1978 (by a Piper Navajo, a cabin-class twin), then continued on up to 6,000 meters, hitting that mark in 5:15. After that, his team loaded up the airplane with fuel, fluids, and some extra heavy stuff from around the hangar for the same profile in category E. Whiteside passed 3,000 meters in 2:30 and hit the 6,000-meter mark at 5:47.

This morning he hit 3,000 meters in 2:05, a full minute and 28 seconds better than the record set in 1978.

The team seems to thrive on a shared purpose that Whiteside works hard to foster. His goal is “to direct this group of guys to the finish line and to do it really well.” He adds: “We’ve had our highs and lows, but we’ve built that trust over the past six years.” He cites the difficulties they had with the engine’s carburetor, as this R-2000 engine came from a de Havilland of Canada DHC-6 Caribou. The air inlet above the Yak’s cowl was designed originally for fighter speed in the high 300-mph range, but the Caribou cruises at about 180 mph, and this was a colossal mismatch that cost them a lot of time when they couldn’t race.

They’re still working on improvements to the airplane and engineering a new impeller for the supercharger. Whiteside has become a record-book hound, and he’s sniffed out a whole list that the Yak can break with its wheels down. In addition to the time-to-climb records, in late April, Whiteside grabbed four more (all awaiting FAI approval): the three-kilometer and 100-kilometer speed records in weight subcategory E and the 15-kilometer speed record in both D and E.

Going after that three-kilometer record puts SteadFast in direct competition with one of the most famous aircraft at the air races. Rare Bear, the powerful Grumman Bearcat that has won three Unlimited Golds since 2002, set the bar at 528.33 mph in 1989 in a category no longer used. This summer, the Bear will take another run at the record in weight subcategory E. Whiteside says, “Bring it on.” He believes that competition for records among the big Reno racers will help publicize the sport.

A former NAA president, Malvern Gross, likened his organization to the U.S. Olympic Committee because of its role in promoting competition and recognizing achievement. Being the best in the world may be its own reward, but it’s even more satisfying when it comes with a medal, or an inscription in a record book where names like Charles Lindbergh and John Glenn are written.

George C. Larson has been writing about aviation since 1972. The former editor of Air & Space/Smithsonian, he’s got a serious jones for large reciprocating engines.