A Note From Ho Chi Minh

In 1968, in the midst of war, Apollo 8 offered a glimmer of hope and humanity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/9b/d49bc97e-1beb-4220-b232-9abaffb0d9fd/as8-14-2383_f75.jpg)

The Apollo 8 flight of December 1968, the first voyage to lunar orbit, was a close second to the Apollo 11 moon landing in terms of its societal impact — one of those rare moments in history where humanity looked outward together and seemed united.

One of my favorite Apollo 8 stories is this anecdote from the novelist William Styron, writing in the foreword to the 1988 book The View From Space:

It was an icy Connecticut evening in a house filled with noisy festivity. My host — a teacher of renown whom I greatly esteem — has a mind of generous curiosity and of eclectic concern, but is a man with a blind spot, at least at that time; he had found the space program a technocratic scam, overblown, financially extravagant, and basically a bore. As close as we always had been we rarely spoke of the astronauts and their flights. I had trouble that evening making him interrupt the party so that we could turn on the television set and follow the progress of the Apollo module as it began its circuit around the moon. Suddenly, there before us was that stark sphere, the craters, the jagged shadows that one knew to be chaotic mounds of rubble, the glistening white landscape projected against a backdrop of unfathomable darkness. The murmur and laughter of the party diminished and died, and we watched in silence while William Anders spoke the words from Genesis:

In the beginning God created

the Heaven and the Earth,

And the Earth was without

form, and void…Ceremonial words tend to sound hollow and inappropriate, generally because they are predictable, touched by the stale hand of prearrangement. But these words, spoken at one of history’s truly heroic ceremonials, seemed entirely appropriate, and I remember that a chill coursed down my back and an odd sigh went through the gathering like a tremor or a wind. Then how was it possible to be more deeply affected, to discover a pitch of eloquence more grand than those incantatory lines? Simple. Listen to Frank Borman, whose cheery valedictory brought home the reality, nearly lost in the sheer awesomeness of the occasion, that we were witnessing the exploits not of some crew of demigods or archangels, but of mortally fleshed men like those of us gathered around a winter’s fire: “Goodbye, good night. Merry Christmas. God bless all of you, all of you on the good earth.”

I glanced at my host, the mistrusting and scornful teacher, and saw on his face an emotion that was depthless and inexpressible.

Last week I heard another Apollo 8 story, just as powerful. It was told by Betty Sue Flowers, an emeritus professor at the University of Texas and former director of the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library, during a National Research Council panel discussion on the future of human spaceflight (more about that meeting in a future post). Flowers, whose academic specialty is the study of mythology, has told the story before (here at an Apollo 8 reunion in 2009). She also included it in an essay in the 2012 book The Transforming Leader, in which she describes her favorite object in the LBJ library.

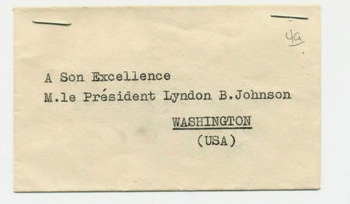

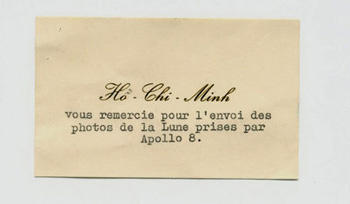

I am haunted by a little piece of paper in the library archives — a note from Ho Chi Minh, leader of North Vietnam, with whom we were at war. It had been sent indirectly, through France. The note simply thanked President Johnson for a picture of the earth rising over the moon — Earthrise, it was called. The picture had been taken in December 1968 by the Apollo 8 astronauts, the first humans to escape earth’s gravitational field, and the first to see the dark side of the moon. As one of his last acts as president, Johnson had sent Earthrise to all the world’s leaders — even to those, such as Fidel Castro and Ho Chi Minh, with whom we had no diplomatic relations. From the transformational perspective of the earth as seen from space, all of us, even our enemies, travel together.