A Road Trip to the Mighty Eighth Museum

Commemorating the sacrifices of U.S. airmen from World War II to today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/df/24df41c3-47ee-4e73-8142-cbb2deeb6caa/city_of_savannah.jpg)

From the highway, the tall, window-scarce building seems unfit for anything but boring office space until just behind it you see the B-47 baking in the Georgia summer sun. During World War II, the story of the Eighth Air Force—better known as “The Mighty Eighth,” and made famous by the bravery of thousands of airmen flying the flak- and fighter-infested skies over Germany in B-17s and B-24s—would begin right here in Savannah with minimal equipment and no clear mission. Yet.

The National Museum of the Mighty Eighth Air Force honors the January 1942 standup of the storied unit at nearby Hunter Army Airfield. The Eighth wouldn’t stay long—its headquarters would be relocated to England the following month to partner with England’s Bomber Command in the burgeoning air war over Europe. By war’s end, the humble beginnings of the Eighth would culminate in a juggernaut of 350,000 men and women, and 3,000 aircraft.

The museum’s lobby is adorned with squadron flags and busts of Air Force elite, including General Jimmy Doolittle, hero of the 1942 raid on Tokyo, and later commander of the Eighth, and General Ira C. Eaker, the Eighth’s second in command, charged with moving it to England. After getting my bearings, I hurry off to the first exhibit. I was struck by the eerie silence of the galleries, which made the sight of a National Socialist German Worker’s Party (SDAP) banner, which was hung from buildings around Germany and in countries under the boot heel of the Reich during World War II, all the more disconcerting. A long display case, filled with a timeline of the Nazi party, as well as German armbands, bayonets, uniforms, and side arms, tells the bloody story of the Nazis, while the sounds of propaganda films play softly in the background. Visitors can inspect every stitch, ribbon, and ripped seam on original Luftwaffe and RAF uniforms.

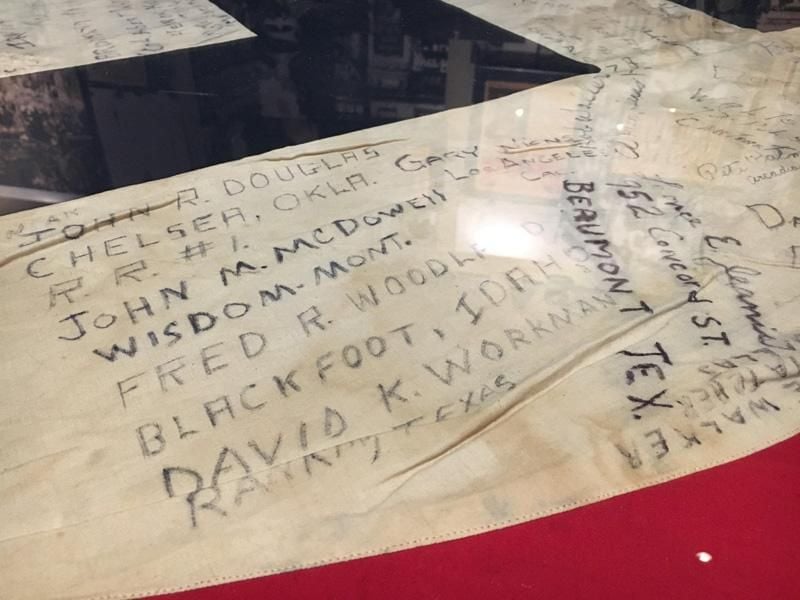

One noteworthy exhibit is a tail section cut from a Messerschmitt Bf 109 shot down over England on August 31, 1940, by First Lieutenant Denys Gilliams. Most remarkable to me was how well preserved the tail section was after surviving a crash more than 70 years ago. I could see every brush stroke and manufacturing detail as if it had rolled off the production line yesterday. In the next section of the museum, a small part of a room has been dedicated to a looped film about the Battle of Britain and a small exhibit about the December 7, 1941 Pearl Harbor attacks. The exhibit includes a bayonet from an Arisaka rifle and a Japanese flag carried by a fallen Japanese soldier. The flag had been signed by the soldier’s family members and friends before he went to war. Nearby, a piece of the USS Arizona sits within a small plexiglass box.

Propped against a replica Nissen hut is a large dull metal wing. On Christmas Eve 1944, Charles W. Haskett, one of the gunners of the Boeing B-17 Lindy Lou, and nine other crewmen set course for Babenhausen Airfield deep into Germany. Over Liege, Belgium, the men and aircraft of the 487th Bomb Group came under attack by scores of German aircraft. The Lindy Lou was ultimately downed by multiple cannon bursts from Focke-Wulf 190s and Bf 109s and most of the crew were captured, except for Haskett, who escaped. Some 50 years later, Haskett learned of a B-17 wing section on display in Belgium near where his aircraft had plummeted to earth, and was able to confirm it was the right wing from his beloved Lindy Lou. (The farmer, in whose field it landed, was using it as the roof for a colony of honey bees.) During a trip to Belgium during which Haskett was welcomed as a hero by the locals, the farmer and his family gave the wing to Haskett. With the assistance of a military museum in Belgium, he donated it to the Mighty Eighth Museum in November 2001.

Near Haskett’s beloved wing is a large interactive map using B-17 models (with my scale-modelers eye I picked out the B-17 models as 1:48 scale), detailing every operation on any airstrip across England at any given time by 1943. Finally, you’re led into the unmistakable epicenter of the museum. Standing in front of me was a B-17G model (identified by the characteristic chin turret) presented in the livery of the 5,000 B-17 to be processed through nearby Hunter Army Airfield, which served as a deployment processing center for men and aircraft during the war even after the Eighth left. I would later learn it is the only restored B-17 in the world with fully operational turrets, and I just happened to miss the final testing of the turret systems by a few days. Walking around the Fortress you can see the level of detail and tireless work that’s been put into the aircraft, and the oil drips on the floor from its Wright R-1820s make it seem like it’s ready for a mission. Years of work have been put into restoring the airframe; the tail section came from a crash in Alaska, and the upper Sperry turret came from Ohio, where the previous owner was using it as a flower pot.

A section of the museum has been dedicated specifically to stories of the capture and escape of downed Allied airmen during the European campaign. Along with a blanket covered in various military patches, collected and stitched by a G.I. as a POW in Germany, more and more flight jackets and equipment begin to appear. Beside the torn Nazi flag and shattered Mauser 98k, an even larger NDSAP flag than the one near the entrance can be seen in a display case, signed by hundreds of Allied pilots freed from Stalag Luft VIIIA. Near the end of the museum is a colorful display of jackets, clothing, patches and other various memorabilia from the Eighth, all donated by former Air Corps veterans.

After a stroll through the garden overlooking Interstate I-95, and a walk around the regal B-47 beckoning people from the highway, I reluctantly made my way back towards the entrance. It was time to get back in the car for the rest of the journey—all the while alert for new gems tucked off the beaten path.