A Rough Ride

The Captain assured the passengers that everything was under control, but I’m sure some of them thought this was the end. I would have.

![]() Turbulence will make any airplane ride less enjoyable. Usually it’s just a minor annoyance and of little concern to frequent flyers. But when the severity increases, even seasoned travelers can become white-knuckle passengers.

Turbulence will make any airplane ride less enjoyable. Usually it’s just a minor annoyance and of little concern to frequent flyers. But when the severity increases, even seasoned travelers can become white-knuckle passengers.

When we describe turbulence in a PIREP (Pilot Report), we use four levels of severity: light, moderate, severe and extreme. Chapter 7 of the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) has a table that precisely defines these levels (including the slight difference between “turbulence” and “chop” for reporting purposes). Reading the definitions, you realize that most turbulence you’ve encountered has been light or moderate. The definition for severe turbulence includes the sentence: “Aircraft may be momentarily out of control.” Extreme turbulence is defined as “turbulence in which the aircraft is violently tossed about and is practically impossible to control. It may cause structural damage.” That’s getting pretty serious, and it’s unlikely you’d encounter severe or extreme turbulence in clear air. It’s within a mature thunderstorm cell where they become more likely, and that’s why we avoid those storms like the plague.

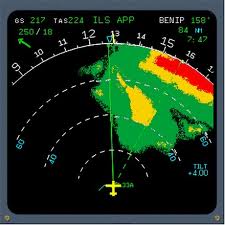

I well remember my worst ride and my only encounter with extreme turbulence: a night flight on November 11, 1995, Dulles to Albany in a British Aerospace J-32, a 19-seat turboprop that was built like a tank. Right after takeoff from Runway 19L, Dulles Departure control gave us a right-hand turn to 330° and a climb to 7,000 feet. As I rolled out of the turn, our weather radar became filled with red (red=severe, probably a level 4 or 5 cell). At first both of us on the flight deck questioned what we were seeing, and wondered if we had a faulty radar. Surely the controller wouldn’t direct us right into a cell.

But then all hell broke loose. Our altitude was changing +/- 1500 feet and the airspeed fluctuated wildly, going from stickshaker (stall) to Vmo (max operating speed, the red line) and back several times. You really don’t want to be operating above the red line. Beyond this speed the manufacturer does not guarantee that the plane will stay in one piece.

When we approached Vmo, I would try to reduce the speed by gently raising the nose and also reducing the power; when we approached stall, I lowered the nose to maintain airspeed. To avoid overstressing the wings and tail, I tried to be as gentle as I could with these control inputs, to keep the g-load at a minimum.

Throughout all this, the plane was shaking so violently that I finally told Tom, the Captain on this flight, “you have the power” while I used both hands on the control wheel. I couldn’t read the instruments, and could only keep a vague sense of our pitch and bank attitude from the artificial horizon. I remember very well my thoughts at the time: (1) Don’t go inverted and (2) I hope it doesn’t get worse. The extreme turbulence lasted probably less than three minutes (though it seemed much longer), and for the next 45 minutes we were in continuous moderate and occasionally severe turbulence. Tom made a few PAs to the passengers in an effort to assure them that everything was under control, but I’m sure some of them thought this was the end. I would have, if I had been in back. Sitting up front, we at least had the benefit of knowing what was going on, and had some (albeit small) feeling of control.

We assessed the situation once we knew we were out of the worst of it, and found that the plane wouldn’t pressurize — which made us wonder just how much the aircraft’s pressure vessel had been compromised. This meant that we couldn’t go above 10,000 feet, and our first inclination was to return to Dulles. But the airport had closed as soon as the weather hit them, minutes after we took off. To return would mean penetrating that same storm again, which was out of the question. We looked into other divert airports, but nothing sounded good in the weather reports. State College, Pennsylvania, was nearby, but a Continental Express plane had just made a go-around there, reporting gusts to 50 knots during the approach.

So, after conferring with our dispatcher, we continued on to Albany . The turbulence abated north of Binghamton. When we shut down at Albany, the passengers didn’t move, and many of them had that 1000-yard stare. We both came into the cabin to talk to anyone who cared to vent or ask questions. After the passengers had gone, we made an entry in the logbook about the pressurization and the encounter with extreme turbulence. That write-up would require an inspection of the airframe before the plane was returned to service the next day.

Once we got to the hotel for our layover, we were both so keyed up we knew we wouldn’t be able to sleep for a while. Though I’m not much of a drinker, I probably could have used one that night. But our layover was less than 12 hours, so we settled for a pizza and couple of soft drinks, and sat in Tom’s room discussing how we had gotten in this situation and what we could have done differently. We came to the realization that no retelling of this event could adequately convey the feeling of being in an airplane that was nearly uncontrollable. You can believe that I will never knowingly penetrate a red cell. Deviate 200 miles to the west? No problem.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Steve-Satre-headshot.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Steve-Satre-headshot.jpg)