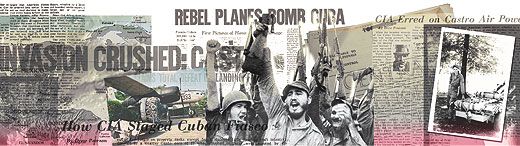

Above and Beyond

Mission: Cuba. Status: Top secret.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Above_and_Beyond_Mission_Cuba_FLASH.jpg)

In early 1961, after I had been out of the Air National Guard for five years, I heard that Brigadier General George Reid Doster, commander of the 117th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing at Birmingham Municipal Airport in Alabama, was looking for me.

When I met with him, he laid it on pretty thick. “We have a very important classified mission I’d like you to consider,” he said. “That’s all I can tell you, other than that you can be of great service to your country.” I would attend a series of meetings with other people contacted for this hush-hush mission. Most of the personnel being interviewed were from the Hayes Aircraft Corporation in Birmingham, where I was working at the time; the rest were active Guardsmen.

Back then, few technicians were familiar with the old Douglas B-26 Invader bomber; fewer still were qualified in its maintenance and electronics, as I was. General Doster asked me to make a decision right then and there. Because I knew most of the guys, I figured I was in good company. I took the job.

Some 40 of us were brought on. We used first names only. I was given a picture of a woman and two kids to go in my billfold—I had no idea who they were—along with other documents that would create a fake identity.

At first we were given just a few vague details about our mission. At each step, a candidate remained only if he continued to sign more secrecy documents. I became pretty sure that we were dealing with the CIA, but this was never acknowledged. We were told how we would be paid and that we could tell no one—not a soul—or we would be prosecuted for revealing classified information.

Finally I learned the truth, and why the Guard needed aircraft technicians: We would be training Cuban exiles to fly B-26s for an invasion of Cuba, with the goal of triggering a revolution to overthrow communist dictator Fidel Castro. Since Castro had B-26s in his air force, the theory went, the Cuban population would think that their own military was revolting against Castro and would join the uprising.

After a week of briefings and paperwork, we reported to Eglin Air Force Base near Pensacola, Florida. We left Eglin at midnight in a Douglas C-54 with blacked-out windows, flying 50 feet above the water for a very long time. We still did not know where we were going.

The next morning we landed on a dusty airstrip. This was our base. There was nothing there except the runway. It turned out to be Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua. I was told that the ground troops for the invasion were being trained in Guatemala while we trained B-26 crews here.

At one time we had as many as 18 B-26s, but the count varied, since airplanes came and went. Where they came from I don’t know. I just did my job, keeping the aircraft operable.

We spent a week or so practicing and preparing, then launched our first bombing mission on the morning of April 15. Eight B-26s, piloted by Cubans we had trained, were tasked to destroy all of Castro’s aircraft on the ground as well as runways and other critical targets. They were then expected to provide close air support to the invasion force. Each aircraft had bomb-release capability and eight .50-caliber nose-mounted machine guns but lacked gun turrets.

We worked all night readying airplanes. When I finished my work and left the flightline, the pilots were just starting their engines. I headed for the shower tent to wash off the grime.

Halfway through my shower a guy came running up, looking for me. “One of the bombers is waiting at the end of the runway and wants you to check their radio now!” he said.

I wrapped a towel around my waist and with shower clogs on my feet rushed out to the runway, where I expected to see a B-26 with its engines shut down. But both propellers were churning. The crew was worried that if they cut the engines, they might not get them restarted, and would I please try to fix their radio?

Due to the canopy arrangement and the proximity of the propellers, the B-26 was a difficult aircraft to climb into and out of—worse if you had to bail out. I wish someone had had a camera that day to take a picture of an idiot—wearing only a towel and shower clogs—climbing up to the cockpit with propeller blades spinning mere inches from his head.

I squirmed into the cockpit and had a look at the radio equipment. The Cuban crew was very tense, probably scared. A submachine gun lay at their feet. I found a loose cannon plug. Once I reconnected it, I asked them to try their radio. It worked, and I managed to get back on the ground without losing my towel or breaking my neck.

After the first bomb run, Washington sent word to stand down until further notice. The lull lasted three days, then another bomb run was attempted. By then Castro had managed to get a Hawker Sea Fury fighter-bomber and an armed T-33 jet trainer airborne. Our B-26s had no chance against them. It was a turkey shoot.

When we resumed the bombing missions, most of the Cuban pilots were shot down. Morale was very low; the Cuban pilots said they would not go back unless Americans flew with them. We learned about the situation at a meeting of all U.S. personnel at Puerto Cabezas and were asked if there was anyone willing to volunteer.

As far as I can recall, eight American advisors stepped up. I wasn’t one of them. As a crew chief, I could offer only moral support and another pair of eyes. I couldn’t see myself sitting there getting shot at with no way to retaliate. But it was not an easy decision. If I had been offered a mounted machine gun, I might have volunteered. But the only guns on our B-26s were in the nose, and those were controlled by the pilot.

The pilots and crew volunteers were people I had worked with at Hayes Aircraft, except for Joe Shannon. In earlier days I had flown with two of them: Riley Shamburger and Pete Ray, whom I considered a friend.

On April 19, we launched six B-26s, four of them piloted by U.S. crews. Wade Gray was flying with Shamburger and was the first American to go down, in the water. The B-26 piloted by Pete Ray and Leo Baker was the second, going down on land. Both airmen survived but were shot by Castro’s soldiers. Only Shannon returned in one piece. The Cuban exiles were unable to sustain the beachhead at the Bay of Pigs and surrendered to Castro’s forces.

The Bay of Pigs invasion failed because the air armada wasn’t used effectively. The plan required air superiority. We were supposed to bomb our targets continuously to prevent Castro from having anything to fly—and even if some of his aircraft survived, his runways were supposed to be so damaged that the aircraft wouldn’t be able to take off.

At Puerto Cabezas, we started to close things down. We had to turn in our Colt .45 automatic pistols, but we could keep the other items we’d been issued. Our baggage was searched at departure.

We returned to Florida in much the same manner we arrived, on a C-54. But the transport’s windows weren’t blacked out and it flew at a much higher altitude. We were reminded that the operation and our involvement in it were still top secret. We were to use the cover stories originally given us and had the name of a person with the Air Guard to contact in case we thought we were being watched or noticed something unusual. Otherwise, we were told to keep quiet and go on with our regular routines.

While I was in Puerto Cabezas, a Cuban technician I had been training came to my tent and told me he did not know my real name but he was going to tell me his, and if I was ever in Miami, I should contact him. “I want to give you something,” he told me. “It’s all I have to give.” He presented me with a brand-new G.I. winter coat. I told him how much I admired him and would gladly accept it.

Today, 50 years after the Bay of Pigs, I still have the coat. I could never tell him who I was—we had been warned that Castro might try to track us down if our real names were ever known. That Cuban technician was a real hero. I wish I knew what happened to him. At least he knew I cared.

James Storie as told to Allan T. Duffin