Above & Beyond: Mantz Versus the Volcano

Filming for Cinerama with a fearless flyer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Above_Beyond_0811_1_MAIN.jpg)

The Cinerama pictures, which debuted in the 1950s, were huge WIDE! WIDE! screen experiential travelogues that plunged the audience into exhilarating realism by casting combined 35-mm images on a giant curved screen. The magic came from three interlocked cameras with a single rotating shutter, mounted in the nose of a B-25 Mitchell bomber flown at treetop level by Paul Mantz, who was on the Cinerama payroll.

In 1955, I was in India as assistant director on one of two crews shooting Seven Wonders of the World. Mantz and his airplane, the second crew, were in Rome when urgent wires from Hollywood directed us to rendezvous in Africa, in the Burundi town called Usumbura (Bujumbura since 1962), at the head of Lake Tanganyika. Our orders were to pull the Cinerama camera from the nose of Mantz’s bomber and shoot a single pickup shot of Mwambutsa IV, the king of Burundi.

I was first to arrive in Usumbura and watched as the tires of the twin-tail bomber slammed into the gravel of the rough jungle runway and rolled to a stop. I’d last seen Mantz and his crew five months earlier, when our paths had crossed in Bahrain.

With the props spinning down, Mantz slammed open the cockpit window and yelled down, “Where’s the goddamn king?”

It took a case of White Horse Scotch to induce his majesty to come by and stand for the 10-second scene. With that out of the way, I sensed that Mantz and his crew of five were casting about for Usumbura’s bright lights and dancing girls (of which there were none). But he did hear about an exquisite Belgian restaurant on the edge of town.

Our party of six arrived at the restaurant, Mantz cuddling a flagon of Smirnoff’s finest while seeking the barman to ensure that protocols of martini assembly were carefully followed. Happily for Mantz, the bartender and owner were the same person, one who took delight in assaying and sharing variations on the Mantz formulation. Then the maps came out.

Mantz had explained the mission of his crew and his aircraft to the restaurant man, and the restaurant man told Mantz about live volcanoes a few hundred miles north of where said crew were getting very drunk. But not so drunk that Mantz failed to see the chance to bill Cinerama for five additional hours of flight time while picking up a tidy bonus for a hazard shot.

Back in the hotel lobby before staggering off to bed, Mantz pointed a quivering finger at me: “Two eggs over easy, crisp bacon, toast, and a gallon of coffee. Everybody up at four. We take off at five. Get it?”

“Sure, Paul,” I said, looking at the Tutsi desk clerk, to whom would fall the task of seeing that these orders were properly executed. He’d heard Mantz, and to make sure he knew we were serious I repeated the command while pressing a twenty into his palm. Over centuries of colonial rule, African clerks had learned to accept a gratuity, assent readily, and smile broadly, with no intention of compliance.

Hours that seemed like a moment later, Mantz and the crew, eyes ringed in red, shuffled into the lobby seeking sustenance. I offered them a dozen green bananas I found in an empty dining room.

By the light of our taxi’s headlights, I joined the crew doing the preflight inspection. I was good at this, having been a Consolidated B-24 mechanic in World War II. We pulled the props through by hand while copilot Frank Schwella checked the fuel tanks with a dipstick. Mantz grumbled about hunger as he plugged wads of cotton in each ear. I dodged his wrath and climbed aboard, hiding behind the bomb bay. I took up station beside the rear gun port and pulled on headphones.

“Contact!” Mantz yelled out the cockpit window. The right-engine starter whined; the engine coughed, again, and caught. The old bomber shuddered. Here we were, six hungover men, with four hours of sleep and no breakfast. We eased forward as Mantz released the brakes and rumbled toward the end of the runway as the first rays of sun splayed over the rooftops of the capital of Burundi, a Belgian protectorate.

Mantz set a course to the north. If he found the fiery mountain and came back with stunning pictures, he would add to his fame. If the mountain could not be found, he could still charge for five hours of flying (see “Hollywood’s Favorite Pilot,” Oct./Nov. 2007). I watched the bomber’s shadow ripple over clustered huts of African villages, over rivers and sandy waste.

“Rescher, you got that camera ready?” Mantz asked. “I don’t want to waste time up there.”

“You fly the goddamn plane, Paul, and I’ll shoot the pictures,” shouted Cinerama cameraman Gayne Rescher.

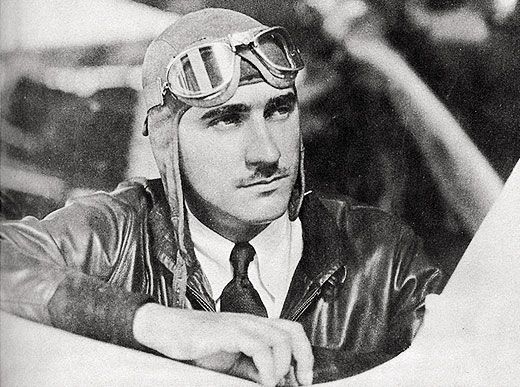

The droning engines set me to pondering the evolution of the stunt pilot and the airplane. They were both born in 1903, the airplane in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, and Mantz in Redwood City, California. The airplane was designed to defy gravity; Mantz would flout the same law. I recalled an earlier time in Greece, Mantz up before dawn with Athens fast asleep, his bomber skimming just above rooftops to capture the golden glow of the Parthenon at sunrise. Or skirting New York’s East River, diving under four bridges before heading out to sea and out of sight of the New York City police.

And the other Mantz, the one that padded quietly into the screening room the first time I saw him? Watching his work on the giant screen, he purred with satisfaction. Or the dinner party on the night before we took off on an around-the-world jaunt to film Seven Wonders. Somehow the names “Amelia Earhart” and “Mantz” came up. “Did you know her?” I asked. “I did,” he said, somewhat condescendingly. “I’ll explain some other time.” As a waiter slipped a menu into his hands, Mantz reached into his breast pocket and brought forth pince-nez attached to a black silk ribbon around his neck. He pinched the tiny levers on the glasses and leaned into the pincers, then straightened his big, square head. After scanning the menu, and without flourish, he removed the glasses and tucked them away. My father, born in the 19th century, had set aside his pince-nez when he saw Franklin Delano Roosevelt wearing same. And now the hotshot Hollywood stunt pilot was affecting the style of Woodrow Wilson at Versailles.

Years later, when I read his biography, I learned that Earhart and her husband, George Palmer Putnam, had spent a month as houseguests of Mantz and his first wife while Mantz served as technical advisor on Earhart’s upcoming around-the-world flight.

A bit later, Rescher cut in: “I think I see it.”

“Yeah, off to the right,” Mantz replied. “That might be it. Another five minutes. Get ready to roll.”

“I want cross light, Paul,” Rescher said. “Lit from the front, it doesn’t mean anything.” They were up front looking at a smoking volcano, and all I could see from my side window was grassland that looked like the Florida panhandle. I heard Mantz change propeller pitch and the engines revved, the bomber banking this way and that.

“I’m coming in from northeast,” Mantz said. “Good for you?”

“Swell.”

From my perch, suddenly, over the edge of the left engine and through the spinning prop, I saw a crater yawn, spewing blue smoke; the airplane banked, plunging into the smoke. Roiling lava fire came ever closer and sulfur fumes filled the cabin. Mantz pulled the bomber into an aching turn. I could no longer force my head to look down. Against gravity’s pull I peered up and saw blue sky above the volcano’s rim. I coughed. An engine coughed in reply. I was comforted that although I had but one breathing system to sustain life, the airplane had two engines. The coughing engine and my choking lungs recovered. Up we went, just over the rim, into sunshine.

“I’d like a couple more takes, Paul, just to make sure,” Rescher said.

Which induced a river of salty language and laughter as the airplane leveled off and headed back.

Sometime later I ran into Mantz on the West Coast, and we talked about the smog in Burbank and the smell of the leather in his new Cadillac. No mention of that dawn flight into the African volcano. To him, it was just another day at the office.