The Accidental Record Setter

How a moonlighting ferry pilot landed in the history books, and other trans-Pacific tales.

:focal(513x115:514x116)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/10/f5/10f50859-d713-4cbb-b6d4-72e625f550ad/accdiental_record_billboard.jpg)

Richard Wiese is sitting on the sofa in his son’s living room in Connecticut. His voice is suffused with more than 80 years of a Long Island lifetime. He’s speaking casually, but he is telling an epic story in full detail for the first time: the story of his record-setting flight across the Pacific.

Ask yourself the question: Who was the Lindbergh of the Pacific—the first pilot to fly that ocean solo? Charles Kingsford-Smith flew across in 1928, but he had a three-man crew. In 1935, Amelia Earhart flew alone from Hawaii to San Francisco—not the whole way. Clyde Pangborn did the whole thing in 1931, but with a copilot.

The first truly solo flight across the Pacific Ocean wasn’t made until after World War II, and by then, it got little attention. How could such an accomplishment be overlooked? It just wasn’t a shock, the way Lindbergh’s flight had been. The age of the jet airliner was dawning. In 1959, the year Wiese made the first solo flight from the United States to Australia, Qantas made the first airliner flight—with a 707—from Australia to the United States. Between 1947 and 1959, a handful of pilots made solo flights that crossed the Pacific on the way to various destinations, and each was, in its own way, a first.

Solo-ish

The first time an airplane flew across the Pacific Ocean with a crew of one, it wasn’t completely alone. On October 28, 1947, George Truman and Clifford Evans set out from Nemoro, Japan, each in a Piper Super Cruiser, aiming for the shore of Alaska. They had already come a very long way—almost all the way around the world.

In 1946, Evans and Truman were flight instructors at College Park Airport in Maryland, just outside Washington, D.C. One day, Evans offhandedly commented that a Piper Cub could be flown around the world. The comment sparked a conversation, then a plan. On August 9, 1947, the two took off in their Pipers from Teterboro Airport in New Jersey for the rest of the world. Eleven weeks and two days later, having crossed the Atlantic, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, they stopped on a little peninsula of the Japanese island of Hokkaido. For the Pacific leg of their journey, they chose a northern route, aiming to make a few stops through the Aleutian Islands to get to Alaska.

The two faced terrible weather, so a local U.S. Air Force commander ordered a pair of B-17s from the Third Emergency Rescue Squadron to escort the little Pipers to their first stop: Shemya Island, one of the Near Islands to the west of the Aleutians.

The escorts took turns circling the Pipers when the far slower airplanes were in view. In the dense precipitation, the bombers lost the Pipers several times. Evans and Truman reached Shemya in 13 hours and 35 minutes. Three days later, they made it to Adak, Alaska. Another three days passed before the final leg to the Alaskan mainland—Fort Randall in Cold Bay. The entire crossing took 211-plus hours of flying over six days.

Truman and Evans landed back at Teterboro on December 10, 1947. They made a brief splash in the press, were hosted by President Truman (no relation to George) at the White House, and just as quickly faded from public view. Although neither was ever completely alone on the Pacific crossing, they proved it could be done. (Evans’ airplane, The City of Washington, is on display at the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center in northern Virginia.)

From Japan to California in a Borrowed Bonanza

Congressman Peter Mack of Illinois looked down at me from his portrait on the wall of his widow Romona’s living room in Chevy Chase, Maryland. The painting had his trademarks—impeccable suit with a red bow tie, and behind him, a Beech Bonanza. Beneath the picture sat his daughter Melanie, and next to her sat Romona. Melanie did most of the talking. “I grew up in an airplane, flying between Springfield and Washington,” she said. “When we would leave Washington, I’d be crying, because all my friends were here. When we left Springfield, my sister would cry, because all her friends were there.”

A naval aviator in World War II, Mack was elected to Congress in 1949. In an article he wrote for Collier’s magazine, he recalled a conversation with a constituent, who said, “The trouble is…our top brass just talks to the top brass of other countries. They never get down to the level of the people themselves, so those people in foreign countries don’t understand us.” Then the man asked Mack: “Why not fly to some of these countries and talk to the people?” The idea stuck.

His constituents raised money to support the flight, and Mack threw himself into the planning. He only needed one thing: an airplane. His friend, Smithsonian curator Paul Garber, had a novel solution. The National Air Museum had recently acquired the Beech Bonanza Waikiki Beach, which pilot Bill Odom had used to make a record nonstop flight from Hawaii to Teterboro in 1949. Garber simply offered the airplane to Mack—as long as Mack would pay for the reconditioning of the airplane. His constituents’ donations paid for the work. Mack renamed the ship Friendship Flame—Abraham Lincoln Good Will Tour.

Mack wrote that his mission was “not to set aviation records, but to try to convince the ordinary people of the world that the United States is only interested in peace and friendship with everyone….” On October 7, 1951, Mack took off from Springfield, Illinois.

Making numerous stops, Mack made his way from Portugal to Japan. He had no staff, no security, and no press entourage. He walked alone through the streets, casually starting up conversations and sharing his good will message.

But then he too faced the Pacific. On January 8 he set out from Tokyo’s Haneda Airport. After his first stop, at Iwo Jima, he left for Wake Island. He got caught in a storm, and as he tried to stay on course, his artificial horizon failed. For the next 10 1/2 hours, he clung to the “needle, ball, and airspeed” method of instrument flying, his eyes “riveted on two dashboard indicators every instant.” When he calculated that he was 150 miles from the island, he also realized he was 30 minutes past his scheduled arrival time, raising the terrifying possibility that he was lost. “Other planes, alerted to expect me, called over the radio, and I tried in vain to acknowledge their calls,” he wrote. “Then a horrible period of radio silence nearly convinced me that I had passed Wake Island.”

Thirty minutes later, he glimpsed some lights through a break in the clouds. Eventually, Wake was only 50 miles away.

The rest of his journey was comparatively easy. Mack stopped at Midway, got his instruments repaired, flew on to Hawaii, and a week later, set out for San Francisco, where he was greeted by a crowd of reporters, photographers, and local officials. The stories referred to his flight from Hawaii, or the round-the-world mission, but most missed the fact that for the first time, the entire Pacific had been flown alone.

Mack made it back to Springfield on April 19, 1952, more than five months after he left. He returned to his life in Washington, meeting Romona on a blind date at a party. They married in 1953.

Melanie and Romona say he put the flight behind him. “Dad loved people,” Melanie remembers. “But he had a mission with the flight, and when it was over, he moved on. He always said that—‘Never look back.’ ” The Bonanza was eventually returned to the Smithsonian; today, it is on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center.

Melanie asked her mother if she would have allowed her dad to make the flight after they’d met. Replied Romona: “No way.”

To Prove It Could Be Done

On July 31, 1958, Pat Boling left the ground in Manila with something to prove—to the world, and to himself. One night nine years earlier, the United Air Lines pilot had had an epiphany. He was waiting for a table at a Honolulu restaurant when he glimpsed Bill Odom lift off on the start of his Hawaii-to-Teterboro record flight. He described his feelings in a letter to his young son Kevin. “In that moment I realized I’d never tested my own courage and capacities,” he wrote, quoting the letter in an article in Reader’s Digest. “More and more I was looking toward a pension, unstimulated by the thoughts of new horizons that had stirred my young manhood.” The idea for a record flight of his own was born.

Unlike Truman, Evans, and Mack, Boling’s goal was to conquer the Pacific, solo and nonstop—and fly farther than Odom had. He would fly from Manila to San Francisco nonstop. He worked with Beechcraft directly, which provided a Bonanza with extra tanks and equipment.

Boling planned his flight meticulously. The fuel was cooled before being loaded into its tanks to ensure the maximum amount of fuel was onboard. He timed the flight to take advantage of a seasonal high-pressure area to give him a constant tailwind. He wore a bright orange flightsuit in case he had to ditch. He left Manila on July 31, 1958. As he headed out over the Philippine Sea, he was “more elated than I had ever felt in my life.”

By the end of the first day, he’d made it over Japan without incident. He continued flying through the night, and confirmed that he was on course the next day over Cold Bay, Alaska. But as he flew toward the Alaskan mainland and into his second night, the weather deteriorated. When he shone a light out onto his wings, he found them covered with ice. He began to descend, and things got worse fast. The engine began to misfire.

Boling headed toward the Queen Charlotte Islands, an archipelago north of British Columbia, which had an airfield. He went over his checklist to ditch and prayed. Gradually the ice began to melt, and the engine kept running. “As the crisis passed, my anxiety was replaced with a strange mixture of weariness and joy,” he wrote.

As the next day dawned, he realized he could reach Seattle, but still hoped for San Francisco. After a fuel leak developed, he landed safely in Pendleton, Oregon, 45 hours, 43 minutes, and almost 7,000 miles from Manila. He’d flown the Pacific nonstop and solo, and he’d broken Odom’s record. (Also in July, ferry pilot Max Conrad flew a Piper Apache from Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, to Taipei, Taiwan, via San Francisco, Canada, Alaska, and Japan, but the flight received little attention.)

Though Boling returned to his airline job, he was never in a rut again.

He Didn’t Want Anyone to Know

Richard Wiese didn’t seek out a Pacific flight—it came to him. A Pan Am navigator and first officer in 1959, he heard rumors of furloughs and layoffs at his airline, so he began ferrying airplanes on the side. “I had three children already and number four was on the way,” he recalls, “and I figured I had to make money somehow, and I wanted to keep flying.”

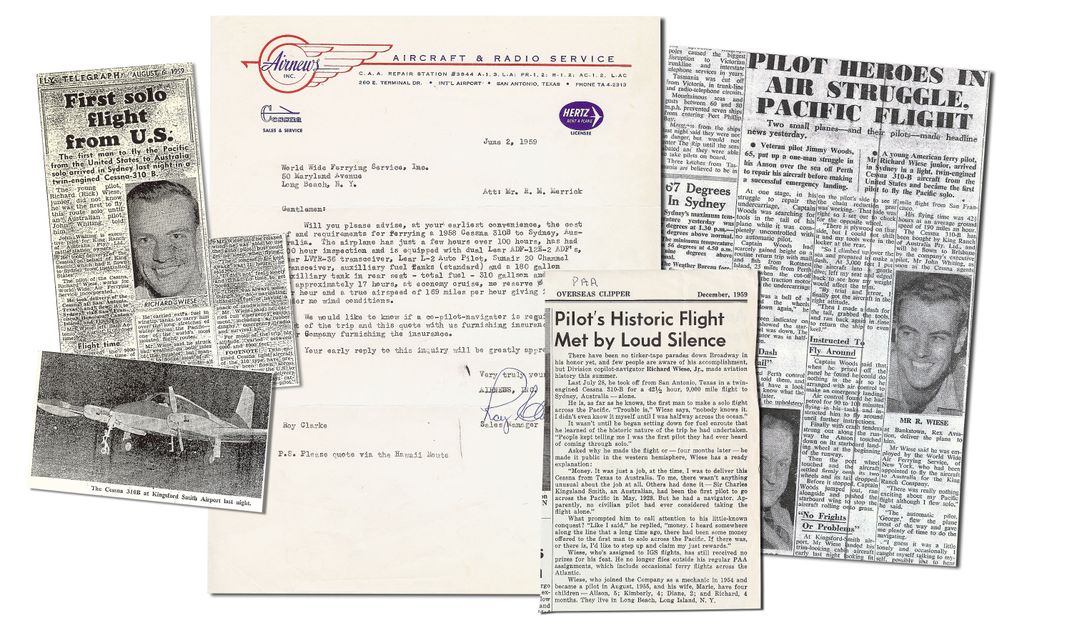

He started working for a ferrying service, flying DC-3s and A-26s to Africa. Then, with a couple of Pan Am friends, he set up his own business, the World Wide Air Ferry Service. One day he received a query from the Air News Aircraft and Radio Service of San Antonio: How much would it cost to fly a Cessna 310B from San Antonio to Sydney, Australia? But it wasn’t Richard Wiese who received the letter. It was Richard M. Merrick.

If you’ve never heard of Merrick, it’s because he never existed. Wiese used an alias for his ferrying gigs, because it was against Pan Am rules to fly such freelance jobs. Richard Merrick helped keep things quiet. Once his ferrying fee ($2,750) was agreed to, Wiese made his way to San Antonio.

On July 28, he flew the Cessna to San Francisco, then left San Francisco after midnight the next day, lifting his heavy little airplane into the fog. When he was in clear skies, Wiese checked his course with his sextant, which was something of a gymnastic feat. “I only had a two-axis autopilot,” he remembers, “so when I leaned forward to take a star shot through the windshield, I’d push the column forward and nose the airplane down.” He would take a deep breath, hold the column steady with his knees, and take the shot. Wiese landed in Hawaii in the early afternoon, more than 14 hours after takeoff, farther than he’d ever flown before. He’d kept himself awake by occasionally banging his head against the window.

After Hawaii, Wiese stopped at Kanton Island, then Fiji. At each stop, he noticed something. In Kanton, the men who helped him refuel said they’d never seen anyone come through solo before. At Fiji, he heard the same thing—and had something of a close call. As he tied down his airplane, two Americans approached him, surprised to see another American flying alone. They were a Pan Am crew, working a freight circuit in the South Pacific. Wiese said nothing about being with Pan Am.

The next day, Wiese passed over the southern tip of New Caledonia, then Brisbane, and after 10 hours, he landed at Kingsford-Smith Airport, in Sydney. “It was just about turning dark,” says Wiese, “and I see these lights—spotlights and whatnot—and there was a crowd of people there.”

The comments he’d heard in Kanton and Fiji about flying solo had arrived before him: Some of the journalists at the airport believed Wiese had just completed the first solo flight across the Pacific. Others got it right: He had made the first solo flight from the United States to Australia.

“They took pictures and so on and so forth,” Wiese continues, “and they asked me my name, and I said ‘Richard Merrick.’ They had had a party for me at the hotel, but I was pretty tired so I went to bed early. And the next day, there were all these newspapers shoved under my door, and there was my real name, Richard Wiese!” (The reporters got his name from the import documents.)

Wiese’s cover was completely blown, but as with all the other trans-Pacific first flights, few took notice. His return flight was on a Pan Am airliner, and when he boarded, Wiese was surprised to see the crew: his new Pan Am friends from Fiji. They graciously invited him up to the cockpit, assuming he’d never been in one before. He never let on otherwise.

As Wiese tells his story today, his son, Richard Wiese Jr., sits next to him, listening. Richard Jr. is the host of ABC’s “Born to Explore,” a television show that follows him around the world. Each program ends with a slightly enigmatic dedication to “The Lone Eagle of the Pacific.” That’s his father.

Richard Jr. remarks on his father’s modesty: “This is the first time I’ve heard this complete story,” he says. “I’ve known bits and pieces. It’s not like growing up my father would sit and we’d go, ‘Here’s this story again.’ There was never any bravado about it.”

Pioneer to Pioneer

Wiese and Boling never met, but years later, they shared another experience, albeit separately. While each was on a routine airline trip, a knock came at the cockpit door. It opened, and in walked Charles Lindbergh.

It was an extraordinary opportunity to hear directly from the man who in 1927 had made the very first solo flight across an ocean, to share with him their own pioneering transoceanic experiences, to connect directly to his legacy. So what did Wiese and Boling say about their flights? Each had exactly the same answer. “Nothing.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/10/f5/10f50859-d713-4cbb-b6d4-72e625f550ad/accdiental_record_billboard.jpg)