In the 1930s Middle East, Airplanes Helped Open the Oil Fields

Pilots flying for the Anglo-Persian Oil Company faced long distances, primitive airfields, sandstorms, breakdowns, and a hostile population.

:focal(2129x1448:2130x1449)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/27/4f/274f4462-bcb8-4f5a-aa68-d42747224e40/39f_fm2020_openerviabparchivearc36131_029_live_copy.jpg)

Drones equipped with cameras and sensors offer an efficient method today to inspect the vast oil fields of the Middle East. “It’s pretty useful if you are operating in the Middle East to know what is going on before you go out into the field,” British Petroleum technology director Curt Smith told Hart Energy in 2015. His words echo the thoughts of Charles Ritchie, a manager for the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, the forerunner of British Petroleum. In 1911, tired of inspecting oil pipelines on horseback, Ritchie decided to import the first airplane into Persia (today’s Iran).

At the time, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company was in the process of testing a new pipeline running from its oilfield at Maidan-i-Naftun to the site of a new refinery at Abadan. The project had brought employment to local people, but such was their enthusiasm for the work that they loosened the bolts on the pipeline at night so that they would be hired to tighten them up the next day. Ritchie was living his own version of Groundhog Day, caught in an endless replay as he rode up and down the pipeline to inspect and fix the leaks only for them to reappear again. In his frustration, he telegraphed his head office: “Send one Blériot monoplane with instruction book.” Barely 18 months had passed since Louis Blériot’s famous flight across the English Channel.

It was a bold move that surprised his colleagues and alarmed officials of the Persian government, who thought that “it would be highly undesirable that it should be used in Persia, where…the Mullahs might make trouble.” The airplane duly arrived, but the instructions were in French, which Ritchie did not understand. A tenacious character, he assembled the machine, distilled his own fuel, and cleared a patch of ground to create a basic airfield. A crowd of employees and locals gathered to watch his first flight. At about three o’clock in the afternoon, the flimsy craft took to the air.

The Anglo-Persian Oil Company magazine, The Naft, recalled the story in a 1934 edition: “Having flown a short distance[,] Mr Ritchie tried to turn round when, unfortunately, the aeroplane came rather close to the surface, so that on banking one of the wings caught a small hillock and, of course, immediately broke and the machine overturned.” His colleagues quickly ran to assist him, but Ritchie, trapped upside down in the cockpit, exclaimed, “Don’t touch anything, you chaps, take a photograph.” The locals remained unfazed throughout the proceedings. Ritchie was unharmed but did not repeat his experiment, preferring his trusty steed for future pipeline inspections. The aircraft itself was recovered and later displayed in the entrance hall of the company’s head office in London.

As oilfield operations expanded, the value of air transport for supply and survey work became apparent to others besides the courageous Charles Ritchie. Not until 1929, however, did the Anglo-Persian Oil Company start its own air service. The company leased a single-engine Junkers F.13 from Junkers-Luftverkehr, which held the airmail concession for the country. The aircraft came with its own pilot, Baron Edgar Viktor von Wangenheim. He had learned to fly in World War I and was the first pilot to fly an airplane from Dessau in Germany via Russia to Persia. He was highly regarded by the company, and when the contract with Junkers ended four years later, he was retained.

These were still the early days of aviation, and journeys were often eventful. On one occasion, von Wangenheim took off in the Junkers F.13 from Baghdad carrying the chairman, Sir John Cadman, to Tehran for meetings with the shah and his ministers. By road, the journey would have taken up to five days, crossing three mountain ranges, but by air it was ordinarily completed in four hours. On this trip, however, the aircraft encountered a heavy snowstorm and was forced to land and stay the night at Kermanshah. The delay stretched into another day when the lubricating oil in the engine froze. Another airplane had to be obtained from Tehran to enable Sir John to complete his journey.

After completing his stint in Persia, von Wangenheim returned to Germany only to perish in an airplane crash in 1937. The Junkers was replaced by a twin-engine de Havilland 89A Dragon Moth supplied and operated by Airwork Ltd. This had a cruising speed of 110 miles per hour and could carry five passengers. Its successor, the DH.89A Dragon Rapide, was used in May 1935 for the company’s first aerial mapping surveys. Within three years, six Rapides were in regular use, the aircraft having proven its reliability and suitability for operating in the oilfields.

One afternoon in the autumn of 1932, two men in resplendent uniforms arrived at the headquarters of the Iraq Petroleum Company in Haifa. On being ushered into the office, they saluted and announced to the astonished manager that they were reporting for duty. Introducing themselves as Captains Mollard and Thomson of Imperial Airways, they proceeded to explain that the Iraq oil company now owned two airplanes parked and ready for use. In fact, the aircraft were 40 miles away at a landing ground at Semakh in the Jordan Valley, that being the nearest regular airfield to Haifa.

Roger Mollard and George Thomson were experienced pilots, and they certainly drew on that experience when it came to flying the aircraft in question. One was an Avro 618 Ten, which carried two crew and eight passengers. It was a three-engine, high-wing monoplane built under license from Fokker. Its passengers suffered excessive levels of noise, vibration, and fumes, while the crew—firmly strapped into an open cockpit—enjoyed a fresh, if stiff, breeze. The aircraft could reach 100 mph with a tail wind, but it had a “marvellous nose for an air pocket,” recalled Iraq Petroleum Company manager J.B.P. Glennie in 1953. This caused the airplane to drop like a stone, leaving the passengers to fend off the luggage that rained down from the racks above.

The other aircraft was a de Havilland DH.50, a single-engine biplane that carried up to three passengers in a box-like cabin, the lid of which was fastened down from outside. The pilot traveled behind them in an open cockpit. The “Fifty” ambled along at a cruising speed of about 85 mph. “She led a blameless life with us for about a year, apart from a slight misunderstanding with a Palestine Railway signal, the ornamental spike of which was found embedded in her tailplane when she landed at Semakh one dirty evening,” wrote Glennie in 1953.

Airfields were few and far between, but this was no problem for a pilot like Gustave Douchy, a French wartime flying ace. He was employed by Société des Transports du Proche Orient, which also provided flying services for the Iraq Petroleum Company, primarily in Syria and Lebanon. His aircraft was a Farman F.190, a single-engine, high-wing monoplane with a cabin for four and an enclosed cockpit. From its base in Homs, the aircraft spent most of its time flying up and down the company’s northern pipeline, with an occasional sortie along the southern pipeline.

Douchy and his aircraft were not always in harmony, however. The Farman’s “shotgun-starter” system often failed to work. On one hot day in the desert, a dozen efforts failed to stir the engine to life. Reaching the limit of his patience, Douchy proceeded to address the engine in “sulphuric” terms, then hit a vital part of it extremely hard with a hammer. Simultaneous roars from the engine and pilot assured the passengers that all was well. In fact Douchy was highly regarded by his passengers, one of whom remarked, “If that man Douchy strapped an engine and propeller to his head and a pair of wings to his arms, I’d fly pick-a-back with him.”

On another occasion, the Farman was approaching Homs aerodrome just after sunset. Its tail wheel caught an electrical powerline and plunged the town into darkness for most of the night. Douchy, unaware of the accident, rang up the electricity company when he arrived home to complain bitterly about their incompetence in causing a blackout. When the Farman was eventually retired from company service, Douchy received a state-of-the-art, twin-engine, low-wing monoplane, a Caudron C.445 Goéland, which included such refinements as a retractable undercarriage and variable-pitch propellers. But, after a number of mishaps, Douchy was forced to admit that the Caudron had to go and reluctantly bade it farewell.

In 1934, the Iraq Petroleum Company introduced the de Havilland Dragon to Iraq. It was smaller and more economical than its predecessors, but it came with a few tricks. In one instance, as the airplane circled above Baghdad airport, the crankshaft in the port engine sheared, and the airscrew landed on the white circle of the aerodrome. After making a safe landing, the captain was congratulated on the accuracy of his aim. A few days later, the Dragon visited Amman. “The service personnel stationed there were naturally keen to see the new Dragon,” recalled Glennie in 1953, and a large crowd gathered to watch, but, as the Dragon taxied out, it began to chase its own tail and spin round in a circle with “the joyous abandon of a puppy.” Such were the sideshows of flying in the Middle East.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/da/7ada8b62-c32c-4162-b3a4-82e38d29f927/39d_fm2020_oilfieldsconcessionareasmiddleeasterncountries_live_copy.jpg)

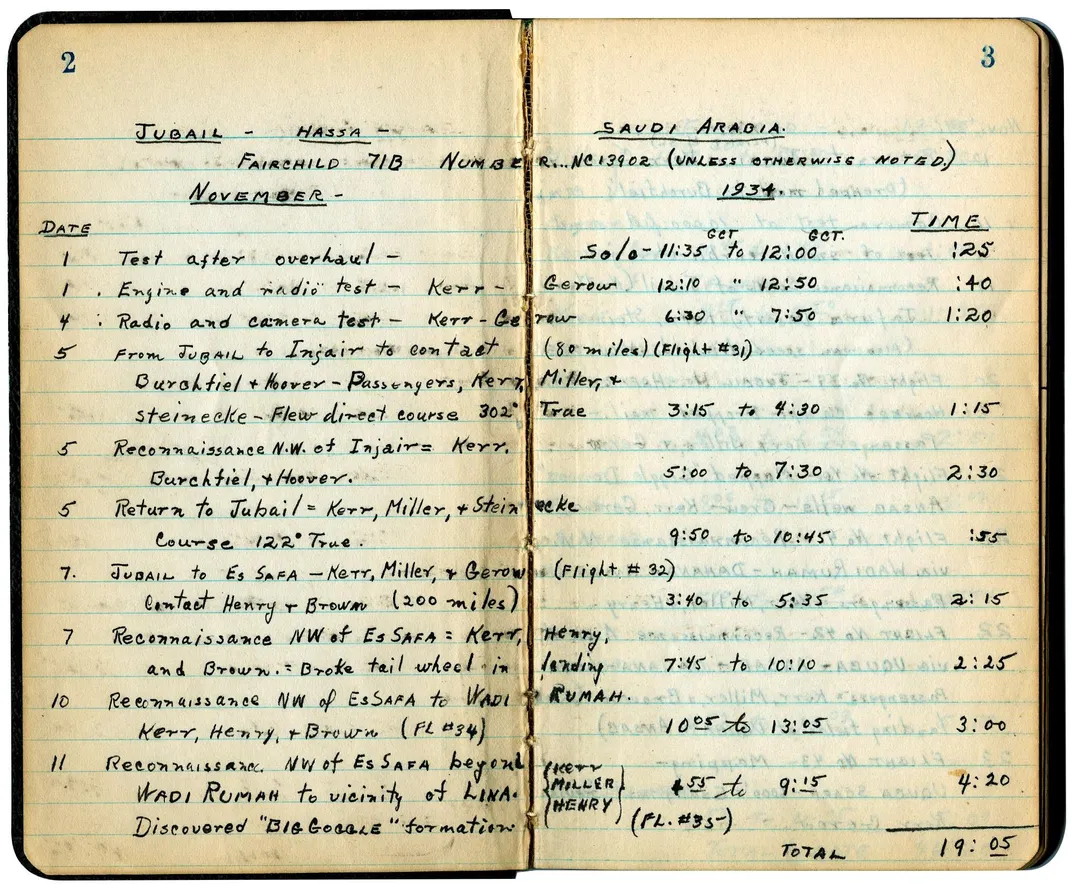

The year 1934 saw the start of aerial surveys in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. After hearing that an American oil company, California Arabian Standard, was bringing a Fairchild 71 to the area, a British official wondered what the “71” might signify: “probably some form of cabin machine,” he mused. Indeed, it had a cabin that could accommodate two crew members and two geologists. It was also adapted for taking aerial photographs, with a hole in the bottom of its fuselage, and carried a Fairchild K-4 camera and special Kodak film for desert conditions.

When pilots Dick Kerr and Charles Rocheville landed the airplane at the Royal Air Force base in Basra in March, they were welcomed, but were warned not to fly directly into Saudi Arabia. They were urged to land in British-protected Bahrain instead. Few, if any, aircraft had flown over the Arabian interior, and it was feared that they might alarm the local population and infuriate the Wahhabi clerics of the land, who were suspicious of Western influences. But the pilots knew that permission to land had already been granted and saw no problem in sticking to their original plan. They headed straight for Saudi Arabia and found the town of Jubail with ease, landing on an airstrip that had recently been scraped out of the desert. But when an elated Kerr jumped out of the airplane, he was promptly arrested.

It was a misunderstanding, of course. The Fairchild was cleared to fly, though subject to conditions: The pilots should observe radio silence, fly high, and stay away from the Bedouin areas of the desert. And, although the airplane’s subsequent career in Saudi Arabia was relatively trouble-free, the incident flagged the problems that would occur elsewhere on the Arabian Peninsula, where various Iraq Petroleum Company-associate companies were prospecting for oil. In Oman, for example, Sultan Said bin Taimur prohibited airplanes from flying over those parts where an imam held sway and he expressed fears for the safety of crews should they make a forced landing. Eventually, he relented, agreeing that oil company aircraft could overfly the area provided they stayed “beyond the range of a rifle.”

On the Trucial Coast (today’s United Arab Emirates), the sheikhs raised few objections, but the cost and the lack of landing grounds were prohibitive and airplanes were not used in oil surveys until after World War II. The RAF and Imperial Airways were allowed to fly over the Persian Gulf, so local people occasionally saw airplanes, but they were completely unused to cars, as geologist Jock Williamson discovered in the 1936-1937 season when he drove toward a group of women collecting firewood in the desert.

“At our approach, they fled screaming into the undergrowth. Our newly acquired friend [guide] was sent to assure them that we intended no harm and after a time came back laughing to tell us that these ignorant people thought that our white van was an aeroplane which had come down from the skies, folded its wings like a bird and was now coming along the ground to devour them.”

The Aden Protectorate, which today is part of Yemen, was the setting for the first aerial reconnaissance by an oil company in southwestern Arabia. In 1938, geologists Ruthven Pike and Henry Wofford arrived for a six-month survey. They used a Short S.22 Scion Senior, chartered and maintained by Imperial Airways. This was a high-wing monoplane with four 80-hp Pobjoy engines and the only land-based example of its type. In addition to the surveys from the air, the geologists made several ground excursions, despite the area’s reputation. Pike wrote in 1938: “I got the impression that the place was somewhat dangerous; that if people left the coast and travelled inland they did so at their own risk: they survived, but did not have an altogether easy time.”

World War II brought a hiatus in oil exploration, but by the time the geologists returned to the region, airplanes had been transformed. They were stronger and faster and had greater range. New techniques, such as magnetic and gravity surveys, were introduced. From Iran to Aden, discoveries were being made, and aerial reconnaissance was now a vital part of the exploration repertoire. In March 1948, geologists were excited to see two anticlines—classic oil-bearing structures—as they flew across the newly opened skies of Oman. But access was still a problem in certain parts. “If only we can get in on the ground,” bemoaned Exploration News, the oil company’s in-house magazine, hinting at the sensitivity of the tribes to foreign intrusion. For despite the advantages of air travel, the tension between Western “progress” and traditional societies remained. The airplane was only the start of things to come.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a5/4b/a54b79a3-ed12-4527-8f58-c06747feac5f/39a_fm2020_rutbahwellsimperialairwaysagsphoto_21626_live_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/55/ae55dca0-9fda-46c7-b2c0-480aa766eda5/39c_fm2020_ammanimperialairwaysagsphoto_29062_live.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/28/f62894f3-b712-45ef-b09d-7cd90d95fb27/39j_fm2020_toswapfor39j_live_copy.jpg)