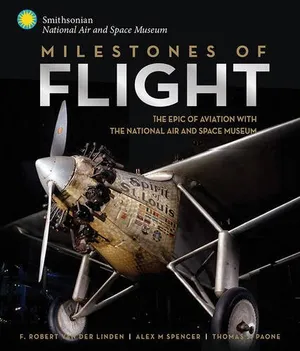

Ten Great Moments in Aerospace History

And you can learn about all of them in one trip to the National Air and Space Museum.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/95/fd959aa3-10d6-48df-ad69-82ba417debe3/16d_jj2016_pipercub_live.jpg)

Forty years ago, on the nation’s bicentennial, President Gerald Ford declared the newly opened National Air and Space Museum a “perfect birthday present from the American people to themselves.” Although the Smithsonian Institution’s aerospace collection had been established much earlier, it wasn’t until the building on the National Mall opened that hundreds of artifacts could be displayed in one exhibition space.

Four decades later, thanks to a $30 million donation from the Boeing Company, the Museum has renovated its entrance hall and begun work on other galleries and educational activities. In recognition of Boeing’s generous gift, the new entrance gallery has been renamed the Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall.

One of the first changes visitors will notice is an interactive wall that introduces them to objects on display within the Museum. By downloading the accompanying Go Flight app onto a smartphone or tablet, visitors can read stories about the artifacts, watch videos of their history, and learn about connections between the world’s most significant air- and spacecraft.

Because the app (available for Android and iOS) can track your location, when you’re in the Museum, it offers you a map to help direct your visit, hour-long guided tours, and a schedule of daily events. If you open the app at home, you’ll get a list of topics that can be tailored to your interests. Each time you open the app, you’ll get a different set of stories.

To celebrate the Museum’s 40th birthday, we’re highlighting 10 iconic objects of the hundreds on display. Through the Go Flight app, any one of these could lead you on a journey through a dozen historic artifacts, showing how one led to the next.

Bell XS-1/X-1

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4b/0d/4b0daf42-e1d0-4644-8765-3c637598f109/16k_jj2016_nasm2014-02315_bellx-1_ericlong_live.jpg)

Imitating the shape of one of the few objects that before 1947 could fly faster than sound—a high-powered bullet—the X-1 broke the sound barrier that year on October 14. Although the revolutionary aircraft enabled NASA and the Air Force to understand transonic flight, the moment that the test pilot, Air Force Captain Chuck Yeager, slipped past Mach 1 appears to have been remarkably uneventful. The wild part of the flight was Yeager’s climb down the ladder from the Boeing B-29 mothership into the rocketplane in its bomb bay—in the slipstream. “There was a metal panel to protect against the wind blast, but it was rather primitive,” Yeager later wrote. “That bitch of a wind took your breath away and chilled you to the bone.”

After the X-1 was dropped from the bomber, Yeager fired the four rocket engines and climbed to 36,000 feet, hitting .88 Mach. He then shut down two of the engines to conserve fuel and climbed to 42,000 feet, where he hit Mach .92. He refired the two inert engines. At that altitude the Mach meter registered .956 and then 1.06—700 mph. “#1 ok,” Yeager wrote in his logbook after the flight.

Aérospatiale-BAC Concorde

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/ee/4fee850a-3035-43b7-8c40-ba903580e5ee/16j_jj2016_concorde_live.jpg)

Supersonic passenger travel was conceived in the 1950s, developed in the 1960s, and realized in the mid-1970s. And for 27 years, the graceful Anglo-French Concorde carried travelers across the Atlantic Ocean in great comfort at twice the speed of sound.

In Europe, enterprising designers in the United Kingdom and France were independently outlining their plans for a supersonic transport, and in November 1962, the two nations agreed to pool their resources and share the risks of developing and building the SST. Despite initial enthusiasm, the airlines declined their purchase options once they calculated the Concorde’s operating costs. Only Air France and British Airways—the national airlines of their countries at the time—flew the 16 production aircraft, and only after acquiring them from their governments at virtually no cost.

Soon, economic realities forced Air France and British Airways to cut back their already limited service, leaving only the transatlantic service to New York. Even on most of these flights, the Concorde was only half full, with many of the passengers flying as guests of the airlines. The average round-trip ticket cost more than $12,000; few could afford to fly.

In April 2003, with maintenance costs spiraling upward and new parts becoming prohibitively expensive, the aircraft were grounded permanently.

Apollo 11 Command Module

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/db/7fdbc0ad-ea97-4634-b125-ab122530c0f9/16a_jj2016_apollo_nasm2016-01617-2_live.jpg)

The living quarters for Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins during their eight-day journey to the moon in July 1969 had an interior of just 210 cubic feet—a little less than the inside of a compact car. It may have felt roomy to Michael Collins, once his two colleagues departed for the lunar surface, leaving him to orbit alone in the Columbia for almost 24 hours. In his book Carrying the Fire, Collins recalls the feeling of solitude: “[R]adio contact with the Earth abruptly cuts off at the instant I disappear behind the moon, I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it.”

Thanks to recent efforts by the Smithsonian’s 3D Digitization Program, we now know what the three men wrote on the walls in that cramped space. The digitization project uses cameras and software that capture information without requiring a person to enter—and potentially damage—the spacecraft. Space history curator Allan Needell seemed most thrilled with the discovery of a calendar, duct-taped to the spacecraft wall, which appeared to have the dates of the mission X’ed out day by day. Noting that in space there is no sunrise or sunset, Needell finds the need to mark the time in days “a very human thing.”

Once the 3D model of Columbia is completed in June, anyone with access to a 3D printer will be able to download and print his own copy of the artifact.

The NACA/NASA Full Scale Wind Tunnel Fan

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4b/0a/4b0a7c6a-67c9-4533-a5a0-dfa89fbc7161/16n_jj2016_fan_nasm2015-02751_live.jpg)

It’s a piece of aviation history that would have been lost if not for the Smithsonian. In February 2015, one of the two fans that drove the 30‑ by 60-foot wind tunnel at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, was installed in the Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall. Built during 1930 and ’31, Langley’s wind tunnel was so immense that aeronautical engineers could, for the first time, conduct tests on full-size aircraft. Until 1945, the tunnel was the largest in the world.

During its 78-year career, the wind tunnel tested nearly every U.S. fighter, including the Lockheed Martin F-22. It also tested the Mercury space capsule, supersonic transport concepts, vertical-takeoff-and-landing aircraft—even submarines and NASCAR racers.

Although the U.S. Department of the Interior had designated the wind tunnel a National Historic Landmark in 1985, it was demolished over a period of two years, beginning in 2011. The drive fan is one of the only items remaining.

Arlington Sisu 1A

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/3f/333fd1de-4772-4e93-bc9a-efd0c6bced8e/16l_jj2016_arlingtonsisu_live-wr.jpg)

On July 31, 1964, Alvin H. Parker flew from his hometown of Odessa, Texas, in a Sisu 1A sailplane and shattered a psychological barrier that had defeated sailplane pilots for years: His was the first flight to exceed 1,000 kilometers (621 miles). The aircraft is now in the Museum.

Leonard Niemi came up with the Sisu in 1952, after stints at Bell Aircraft and Curtiss-Wright. He designed the airplane to be buildable by people in home workshops, but the first flight of the prototype Sisu 1, in 1958, was so successful that he decided not to sell plans or kits to homebuilders. Instead, Niemi modified the design for production as a ready-to-fly sailplane.

Construction began on the first four sailplanes in 1960. Pilots snapped up the finished aircraft, but production costs surpassed profits, and Niemi had to sell the project.

Niemi had a team at Mississippi State University refine the surface contours on his second Sisu (the team’s techniques are still secret). Niemi took the sailplane into the air for the first time on May 1, 1963. Parker bought this Sisu, and a year and 10 days later, he took off from Ector County Airport, north of Odessa, and released from the towplane just before 10 a.m. Ten and a half hours later, he touched down in Nebraska, setting a world distance record.

Bell UH-1H Iroquois

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6a/d2/6ad2a519-1bbe-4c84-99a8-2147af19acf9/16f_jj2016_hueyuh-1h-15_live.jpg)

Known almost universally as the Huey, Bell Helicopter’s Models 204 and 205 were used by all U.S. military services, many U.S. allies, and numerous civilian operators. The military’s reliance on the Huey during the Vietnam War made it one of the most enduring symbols of the conflict.

U.S. involvement in the war began in earnest in 1962, and the lack of conventional roads and other infrastructure in South Vietnam made the military depend on the helicopter for counterinsurgency operations against Viet Cong guerrillas, who controlled much of the territory. As the war progressed, military operations took the form of quick strikes into the countryside, much of which was covered by the marshes and rice paddies of the delta, dense interior jungle, or rugged hills and mountains.

The Huey was not the only helicopter type used in Vietnam, but it was the most prominent. Of the 12,000 U.S. helicopters that served in Southeast Asia between 1961 and 1975, 7,000 were Hueys, and most were employed by the U.S. Army. Hueys also made up two-thirds of the helicopter losses in Southeast Asia; more than 3,300 were shot down or destroyed by accidents, in nearly equal quantities.

No U.S. military aircraft since World War II’s B-24 bomber has been produced in greater numbers than the Huey.

Space Shuttle Discovery

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/85/7785c65a-37ce-43b8-bc70-652c95bbe0fb/16i_jj2016_discovery9-12-12_020_live-wr.jpg)

After 39 missions, 365 days in space, 5,830 orbits, and 148 million miles, the space shuttle Discovery was delivered to the National Air and Space Museum in April 2012.

“When a curator is considering collecting an artifact,” says Valerie Neal, a curator in the Museum’s space history division, “there are a number of standards that are applied. The principal one is historical significance. Then we look at the nature of the object itself. Is it the only one? Is it rare? Is it the first one? Is it the last one? Discovery gets an A on every measure.”

Consider: Discovery deployed the Hubble Space Telescope. Took the first Russian cosmonaut to fly on a shuttle into space. Brought John Glenn back into space 36 years after he became the first American to orbit Earth. It returned the country to spaceflight after the Challenger and Columbia tragedies. It flew the first mission with a female shuttle pilot—Eileen Collins on STS-63. It was the first shuttle to dock with the International Space Station. The shuttle program helped increase knowledge in astronomy and astrophysics, Earth science, materials processing, life sciences, and engineering. Continuing its role as the do-everything spacecraft, Discovery now serves as an educational tool for the millions who visit the Museum each year.

Piper J-3 Cub

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/95/fd959aa3-10d6-48df-ad69-82ba417debe3/16d_jj2016_pipercub_live.jpg)

Created as a trainer to foster aviation during the Depression, the Cub became a ubiquitous utility aircraft in World War II. Since 1932, thousands of pilots have learned to fly in Cubs, and in the 21st century thousands more continue to fly them, along with their light sport and bushplane derivatives. The Cub’s success was due to two men: C.G. Taylor, who designed the aircraft, and William Piper, who provided financial stability and marketing genius to the manufacturer. By 1941, one-third of all general aviation aircraft were Taylor or Piper Cubs.

To compete in the lightplane market, Piper introduced the J-3 in late 1937 with such “luxuries” as brakes, a steerable tailwheel, upholstered (instead of plywood) seats, a compass, an airspeed indicator, and more legroom (the firewall was moved forward). Priced at $1,300, then reduced in 1939 to $995, it was a resounding success with fixed-base operators, flight schools, and air-minded citizens who, due to easing economic times, could now afford to learn to fly. From 1938 to 1947, Piper built about 19,888 J-3s.

During World War II, more than 5,600 Cubs flew in and out of short fields as liaison, observation, and ambulance airplanes, hedgehopping over battlefields or ferrying officers. The Cubs supported invasions in North Africa, Europe, and the Pacific. The Piper L-4 Miss Me is credited with the last aerial victory in Europe, when its crew used pistols to bring down a German Fieseler Storch.

Boeing B-29 Enola Gay

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/96/b69687e4-0d12-4350-add2-fb2ef8cd44d2/16g_jj2016_enolagay_live.jpg)

At the end of World War II, the Superfortress was the most advanced propeller-driven airplane in the world, a marvel representing the latest advances in U.S. aeronautical engineering, bomber design, and strategic bombing doctrine.

Even before the first test of an atomic bomb, the U.S. Army Air Forces began work, in June 1943, on Project Silverplate, a program to modify B-29s into atomic bombers. The first 15 Silverplate B-29s were produced at the Glenn L. Martin factory in Omaha. Colonel Paul W. Tibbets Jr., commander of the group formed to deliver the weapons created by the Manhattan Project, selected one as his personal aircraft and named it after his mother.

Tibbets and his crew took off from the island of Tinian at 2:45 a.m. on August 6, 1945, and at 9:15 a.m., the Enola Gay, flying at 31,000 feet, dropped the world’s first atomic bomb. In an explosion equivalent to 16 kilotons of TNT, the bomb killed an estimated 60,000 people instantly. Another 60,000 died later from radiation sickness and related injuries. The single bomb destroyed 4.7 square miles of Hiroshima and left less than 20 percent of the city’s buildings standing.

In 1946, the Army Air Forces transferred the Enola Gay to the Smithsonian Institution. Its restoration, begun in December 1984, was the largest such project the Museum has ever undertaken, requiring nearly two decades and approximately 300,000 hours to complete. The challenge included polishing virtually every square inch of the bare aluminum surface, and refurbishing all four R-3350 engines.

Sikorsky HH-52A Seaguard

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/53/56/5356adcc-31a8-4693-8ead-083436356fef/16c_jj2016_sikorskyhh2helicopter_live.jpg)

The two sailors climbed onto the tanker’s handrail for one reason: The heat of the ship’s steel deck was melting their shoes. It was November 1, 1979, and the tanker Burmah Agate had collided with the freighter Mimosa in the Gulf of Mexico, igniting the tanker’s 300,000 barrels of oil.

The two sailors watched the tanker burning around them. Then, through the smoke, they saw a Coast Guard helicopter approach: a Sikorsky HH-52, tail no. 1426, piloted by J.C. Cobb and Chris Kilgore, along with Petty Officer Thomas Wynn.

That day the Sikorsky, along with a second helicopter, rescued the two sailors perched on the handrail and 25 other men; they were the only survivors from the Burmah Agate.

The storied helicopter is now in the collection of the National Air and Space Museum. In 1988, as the Coast Guard was replacing its fleet of HH-52As, Lieutenant Thomas King was asked to find homes for almost 75 of them. King retired the next year but continued his work, as a member of the Coast Guard Aviation Association. Once the Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center opened in 2003, the Smithsonian was able to accept a Seaguard: It was the national collection’s first Coast Guard aircraft. There was one catch: The Museum required the helicopter to be fully restored. In late 2014 the association acquired no. 1426 from the North Valley Occupation Center, a vocational-technical school in Van Nuys, California. In little more than a year, a group of volunteers restored it, and now, at last, it’s on display.