On a Snow-Covered Mountain in Afghanistan, John Chapman Made a Heroic One-Man Stand

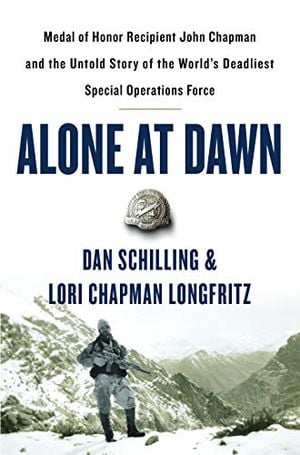

A new book recounts the Medal of Honor winner’s story.

:focal(647x196:648x197)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/45/76457a2c-1b93-4d9d-9e21-012268a789de/23b_sep2019_leadbookcover_live.jpg)

Dan Schilling, who spent more than 30 years in the military, and Lori Chapman Longfritz, John Chapman’s sister, have written Alone at Dawn, an unblinking look at what happened when a combat rescue went wrong. The story relates how Chapman, a U.S. Air Force combat controller, fended off al Qaeda fighters even after he was shot and mortally wounded. His actions that day in March 2002—for which he posthumously received the Medal of Honor—saved 23 men, including a team of U.S. Navy SEALs. The book also reports on the work and culture of combat controllers. Dan Schilling spoke with Air & Space senior associate editor Diane Tedeschi in July.

Air & Space: Why did you decide to write this book?

Schilling: The book actually came to me through Chapman’s sister, my co-author Lori, who’d been trying to write it for a number of years. Initially, I agreed only to help her shape a proposal and introduce her to my [literary] agent. I wasn’t interested in going into what—for me—was my own past. A couple sleepless weeks followed our conversation, which led to the realization that I had to write it because I knew all the parties involved and had been a combat controller most of my career.”

Did Chapman’s actions that morning exceed the call of duty?

Undoubtedly. His decisions were to a calling higher than duty. It was love for those he fought with, extending to those he didn’t even know. Love is not a term used by people to describe combat, but it’s accurate in my experience, having been in combat, and the truest essence of his actions.

What are the most important skills a combat controller should have?

Tenacity and a drive to do whatever it takes to accomplish what is before you. I’d add that the best controllers I’ve known throughout my 30-plus years in service were all intellectually very curious individuals.

What is the washout rate for students going through the combat controller program?

Around 90 percent. The combat control community continues to work hard at improving that attrition number because we are critically short of controllers, though for obvious reasons the standards remain inviolate.

Is it typical for a combat controller to be deployed alone?

Yes, in the sense that they are not with other combat controllers. Typically, we are attached to sister special-operations-force organizations such as SEALs or Green Berets. The result is that the combat control community works with the best of every service, which allows you to learn a diverse set of tactics. The downside is you are one man—alone—with the responsibility for everyone. If you fail, everyone dies.

Do the qualifications for combat controllers exceed those required by the other U.S. special operations forces?

In a word, yes. Though there are a lot of subtleties involved in training highly capable operators like those at Delta Force or SEAL Team Six. But to produce the initial individual, the training for combat control is longer, more intellectually demanding, just as physically challenging, and more expensive than for any other special operations force. The foundation for operating—shooting, parachuting, combat scuba diving, demolitions, and tactical prowess—is the same for all special operations forces. What separates combat control from all the others is the understanding and application of four-dimensional space on the battlefield. They are, in fact, trained air traffic controllers.

Are combat controllers often the first to arrive to a scene of combat operations?

Yes. Because they can operate anywhere unsupported and arrive before anyone else by any means necessary. This extends beyond combat, though. They are often diverted to humanitarian crises around the world before anyone else responds.

One of the examples I like sharing is the [2010 earthquake in Haiti]. The first responder was an eight-man combat control team led by a master sergeant named Tony Travis. The team established the international airport in 28 minutes, and ran the global relief effort for two weeks unsupported, exceeding the maximum capacity of the airport by a staggering 1,400 percent. In fact, Tony was given a letter from the president of Haiti granting him sovereignty of all Haitian airspace. This was a sergeant in the U.S. Air Force.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.