The Real Aerial Battles That Inspired Star Wars

Born one year before the end of World War II, George Lucas turned a boyhood fascination into a space epic.

:focal(1071x738:1072x739)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/84/22/8422ab1e-f103-4eff-aca9-99e345369312/02m_on2020_starwars1a_live.jpg)

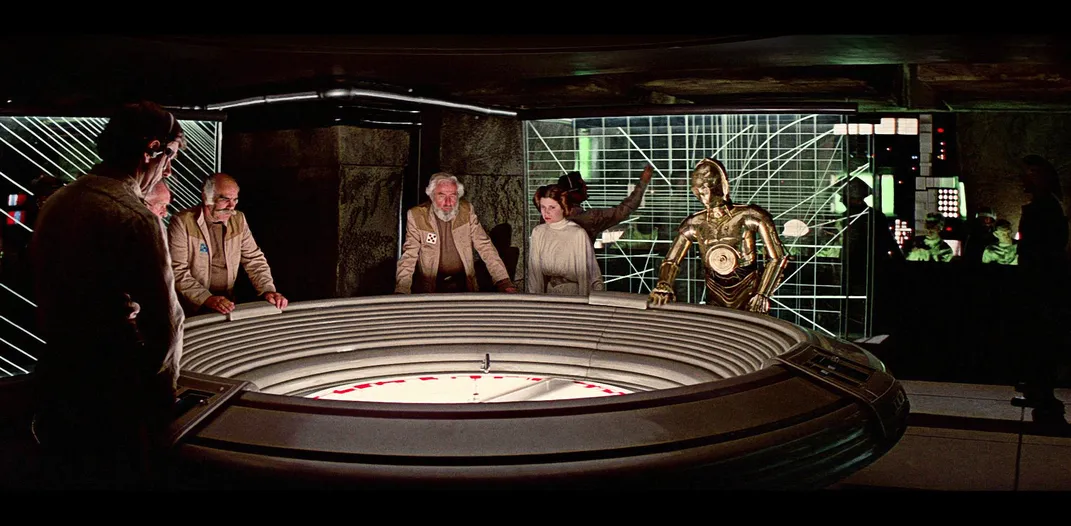

In early 1977, director George Lucas invited some of his friends and associates to view a rough cut of his latest project. It was a kids’ movie that in one early draft had sagged under the title Adventures of the Starkiller, Episode One: The Star Wars. The crowd he’d summoned to his Bay Area home were at least outwardly just like him: Filmmakers with major successes under their belts though not one of them was yet 35 years old. They included screenwriters Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, who’d worked with Lucas on his 1973 smash American Graffiti, and directors John Milius, Brian De Palma, and Steven Spielberg.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f0/fb/f0fb0323-31f7-4cd2-89ec-ece5242ec90c/02l_on2020_starwars1d_live.jpg)

When the lights came up, there was embarrassed silence. The movie was long, poorly acted, and staggeringly weird. Lucas was stung by his peers’ feedback. De Palma, who’d just had his first big hit with the 1975 Stephen King adaptation Carrie and would go on to make blockbusters like The Untouchables and the first Mission: Impossible, was particularly brutal, poking fun at Princess Leia’s hair and the frequent references to “The Force.” He also mocked the muffled voice of Darth Vader, whose dialogue had not yet been menacingly dubbed by James Earl Jones (to the chagrin of actor David Prowse, who played the towering villain on camera), and howled at the movie’s tedious six-paragraph opening crawl (later slimmed down, with De Palma’s help, to three). While no one else was as acerbic as De Palma or as optimistic as Spielberg, there was a clear consensus that Star Wars needed a lot of work before its Memorial Day weekend 1977 release date.

It didn’t help that the rough cut had incomplete sound effects, lacked the musical score that would eventually win an Academy Award for composer John Williams, and was slathered in grease pencil streaks to take the place of laser fire. In fact, nearly all the special effects were unfinished. The climactic space battle, wherein dozens of screaming (yes, in space, but don’t worry about it) fighters shoot it out over a gigantic Imperial space station the Rebel Alliance is trying to destroy, had so many placeholder shots it was nearly impossible to follow.

To assemble this primitive cut, Lucas had recorded hours of wartime newsreel and movie footage on videotape, transferred the snippets onto 16mm film, and dropped the vintage shots into the movie in place of the missing scenes of space fighters. The effect was confounding. “So one second you’re with the Wookiee in the spaceship and the next you’re in The Bridges at Toko-Ri,” recalled Huyck in an interview years later. “It was like, ‘George, what-is-going-on?’ ”

Over a group lunch after the screening, De Palma scoffed that Star Wars was good for only eight to 10 million dollars, but Spielberg predicted the film would gross 100 million. “And I’ll tell you why,” he said to the gathering. “It has a marvelous innocence and naiveté to it, which is George, and people will love it.”

We know now that Spielberg was right. In fact, he underestimated. To date the movie, now retitled Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope, has grossed more than $775 million worldwide. And that sum leaves out the additional billions generated by sequels, spin-offs, and merchandise over the four decades following its initial release.

The discombobulating war-film excerpts may have failed to beguile viewers at Lucas’ San Anselmo home, but that was not their primary purpose. These clips of spinning Spitfires and coldly mechanical Messerschmitts were being used to communicate with the visual effects (VFX) crews working nonstop to finish the movie’s climax.

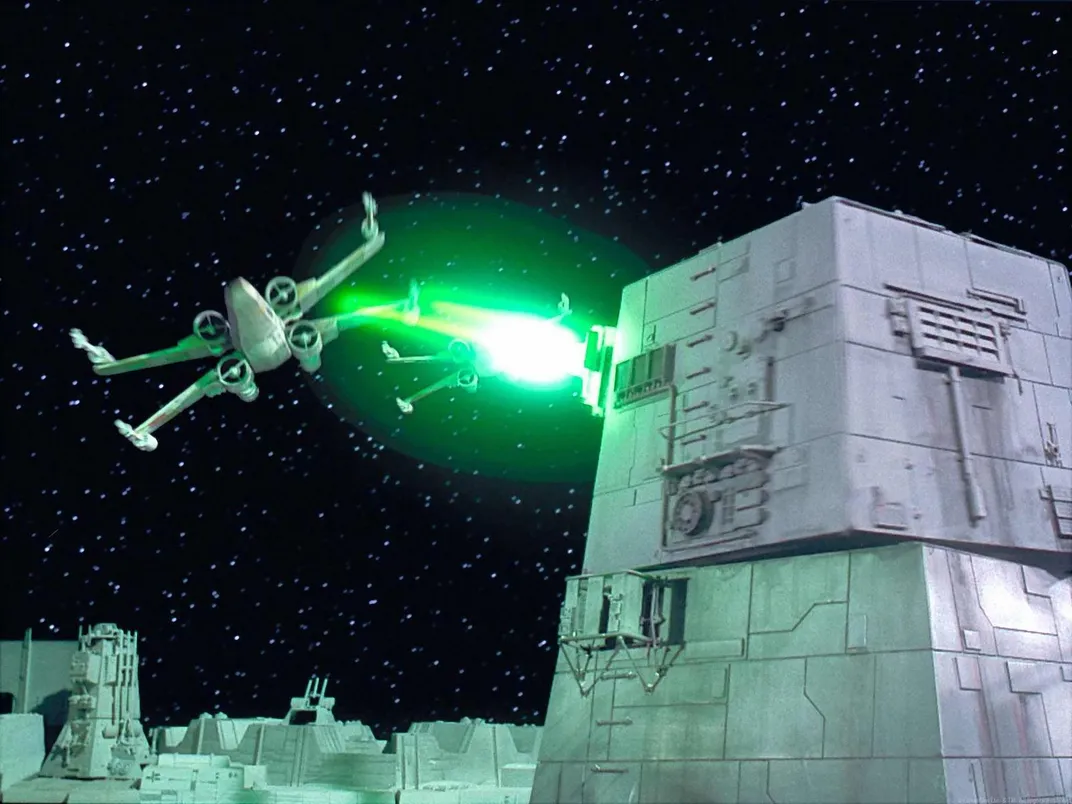

Imagery of U.S. fighters during Stateside training exercises, lifted from a jittery newsreel, showed aircraft peeling out of formation and dropping from sight. The clip was used as a model for the memorable shot of Rebel craft diving to attack the Death Star. One at a time, the fictional spaceships elegantly “aileron roll” across the screen, mimicking the movements of the 1940s aircraft almost exactly.

Some 45 shots later—about 75 seconds of screen time—Jek Porkins’ X-wing fighter becomes the first casualty of the desperate raid. The visual cues that inspired the starfighter’s demise came from a panning shot taken by a nervy U.S. Navy cameraman in the midst of a harrowing kamikaze attack in the Pacific more than 30 years earlier. The sailor captured the final moments of a Japanese Zero as it burnt up over the deck of an American aircraft carrier. As VFX artist Paul Huston described the shot in the book Star Wars Storyboards: The Original Trilogy, “[An artist] would show me a shot of a Japanese Zero flying left to right in front of a conning tower of an aircraft carrier and say, ‘The aircraft carrier is the Death Star, the Zero is an X-wing. Do a board like that.’ ” The art became storyboard 168, shot 245, which was entitled, “PORKINS’ X WING COMES APART IN FLAMING PIECES.”

War movies and hot rod automobiles had shaped George Lucas’ young life in Modesto, California in the 1950s. Both interests can be seen in the genesis of the space fighters in Star Wars. In the movie’s climactic sequence, the Rebels’ X-wing and Y-wing squadrons operate as a complimentary set. Their pairing recalls the immortal Battle of Britain team: Supermarine Spitfires and Hawker Hurricanes had gallantly fought over England in 1940 and again on the silver screen in 1969’s Battle of Britain, a Lucas favorite.

The X-wing was the racy, handsome star of the show. When Lucas discussed the ship with California model maker and concept artist Colin Cantwell, he said he wanted it to look sleek and fast. The X-wing conceptual model’s nose was stolen from a 1960s Revell 1/16 scale dragster model kit. The far aft position of its cockpit turned the ship into a cosmic Corsair fighter. Its strange split wings, which open up from two wings into four as the fighter goes into combat, came from Cantwell.

Photogenic and eventually iconic, the X-wing was destined to appear on lunchboxes and T-shirts for decades. Its popularity is not unlike the preference wartime magazine photographers showed toward the stunning Spitfire fighter, while the workhorse Hurricane was all but ignored. Lucas’ war-wagon Y-wing received similar treatment.

The underdog starship was older, slower, and bigger than its stablemate. Like the earthbound T-bucket hot rods Lucas admired in his youth, the Y-wing had been heavily modified in an effort to keep up with the times. With discarded hull plates, skeletal cowlings, and reduced weaponry, the old machine could possibly pass as a fighter-bomber. The efforts to lighten the ship echo the conversion of 1940s fighters into speedier reconnaissance aircraft by stripping them of armor and guns.

The Y-wing’s distinctive twin booms and centrally placed cockpit echo the hometown hero of its creators. Industrial Light & Magic—the Lucas-founded VFX house that built the models—was located in a warehouse just a few miles down Vanowen Street in Burbank, where Lockheed had assembled P-38 Lightnings 30 years earlier.

The fighters were key to Lucas’ lived-in aesthetic. Unlike the ships in 2001 or Star Trek, the Rebel spacecraft were battered and scorched, resembling the ground-attack P-47s in France, which quickly became patched, bleached, and caked with mud. The Y-wings managed to look at once futuristic and obsolete, more like a teenager’s lovingly patched-together muscle car at Venice Beach than lightspeed-capable starships from a distant galaxy.

By contrast, the Imperial ships were clean, dark, and angular. The cold aesthetic of their Twin Ion Engine (TIE) fighters owes something to the Luftwaffe’s Messerschmitt Bf 109, a design that Germany found relatively easy to build quickly and in great numbers. A character in one Star Wars spin-off novel notes the basic TIE fighter is “a commodity which, after hydrogen and stupidity, was the most plentiful in the galaxy.” Nevertheless, they come screaming in from above on our startled heroes in much the same way the real German interceptors ambushed Royal Air Force pilots Douglas Bader and “Sailor” Malan over the English Channel.

The Death Star attack is all about combat in the face of desperate odds. It’s a clear homage to the epic air battles seen in movies from the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1954 Korean War film The Bridges at Toko-Ri, Navy pilots attack a group of strategically critical bridges in North Korea, defended by murderous anti-aircraft fire. In the World War II film The Dam Busters, released the following year, RAF Lancaster pilots raid a strategically critical dam, also heavily defended by anti-aircraft fire. In 1964’s 633 Squadron (based on the 1956 book) RAF Mosquito pilots take on a German rocket fuel plant in Norway which is, you guessed it, heavily defended by anti-aircraft fire. But 633 Squadron adds a twist: The aircraft must navigate a high-walled fjord at high speed, braving storms of gunfire. This memorable scene was one of Lucas’ main inspirations for the trench run in Star Wars.

While 633 Squadron provided much of the physical environment for the Death Star raid, The Dam Busters supplied the fliers’ tactics and radio communications. As the Rebel ships assemble, Luke Skywalker becomes one of a chorus of voices checking in with, “Red Five standing by.” In The Dam Busters, the Lancaster pilots chime “Here leader,” over the radio. Then, in both movies, someone breaks in to marvel at the size of the target.

In the next scene in both films, squad leaders valiantly draw fire away from the craft making runs on the targets. In The Dam Busters, Guy Gibson asks his tail gunner, “How many guns do you think there are, Trevor?”

“I’d say there are about 10 guns, some in the field and some in the towers,” the gunner replies.

In Star Wars, Red Leader asks a Y-wing pilot, “How many guns do you think, Gold Five?” The reply: “Say about 20 guns, some on the surface, some on the towers.”

The Rebels suffer heavy losses and the raid teeters on the brink of failure, until a pivotal moment when Millennium Falcon comes diving out of the “sun,” a trick as old as military aviation itself. The Falcon is a hefty machine compared to the starfighters. And everyone besides Han Solo knows it’s not as fast as they are. Industrial Light & Magic put the sub-light cruising speed of this storied YT-1300 Corellian light freighter at roughly three quarters that of an X-wing—more like a bomber than a fighter. The Falcon’s cockpit was strikingly similar to the glass greenhouse nose of a Boeing B-29. And like the Superfortress, the Falcon sports defensive gun turrets.

Star Wars’ $11 million budget was thrifty relative to the film’s scale. In 2020 dollars, that’s about $47 million. By contrast, the most recent Star Wars sequel, 2019’s The Rise of Skywalker, had a reported budget of $275 million. To pinch pennies back in 1976, ILM model-makers used parts of rejected kits from the Monogram model company in Hawthorne, California to texture their Millennium Falcon prop. A close observer can see hatches, mantelets, and rear decks from World War II Panther and Tiger tanks worked into the Falcon’s skin, along with fragments of airplanes, trucks, and artillery pieces.

The Falcon’s sound, too, came from the engines of World War II aircraft. Sound designer Ben Burtt traveled to the air races in Mojave in the mid-70s. “I just said, ‘I want to record some planes,’ and they said ‘Yeah? Then go on out there.’ You could never do that nowadays. I was out at the pylons, and planes were passing 15 feet above my head. They were so fast that I could hardly see them go by; they were just a blur, though I could smell the oil and exhaust…. Almost all of the spaceships came out of those Mojave recordings, including the Falcon.” Burtt radically slowed the Doppler-warped sounds of Packard Merlin engines from P-51 Mustangs to create the flyby sound effect, sometimes adding a thunderclap or even a lion’s roar.

That attention to fantasy-burnishing detail paid off. In his just-published memoir, film editor Paul Hirsch, who won an Academy Award for his work on the movie, calls Star Wars’ first test screening for a public audience—months after that private screening for his pals had left Lucas so discouraged—“the most exciting screening I have ever been to in my life.”

Hirsch recalls that the famous shot of the stars stretching out beyond the Falcon’s canopy as the ship jumps to light speed “had people jumping out of their seats, something I had never seen before and have never seen since. It was as if they were rooting for a baseball team that had just won the seventh game of the World Series with a walk-off home run in the bottom of the ninth.”

Lucas had told his editor to expect more changes. But after witnessing the ecstatic reception of the audience that night, the soft-spoken Lucas shrugged, “I guess we’ll just leave it alone.”

Hirsch speculates, as many other writers have over the last 40 years, that a collective yearning for the moral certainties of the 1940s was a big part of what made Star Wars such a phenomenon in the fractured and uncertain ’70s. In fantasy as in history, we like to see the good guys win.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7b/ac/7baccdd0-caa3-4d9a-80fd-fffa3fc31ad9/02h_on2020_starwars9axwing_live.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/4c/c34c9953-02c8-4d6c-a3c6-dbc73f4be6c7/02c_on2020_starwarsmedalceremony_live.jpg)