Cairo to Baghdad in 1921

The Royal Air Force pioneered a route over 540 miles of empty desert—to deliver the mail.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/78/74/78742806-c1ab-4b39-b442-5bd72b5a08c0/airmailsleavinghinaidi_live.jpg)

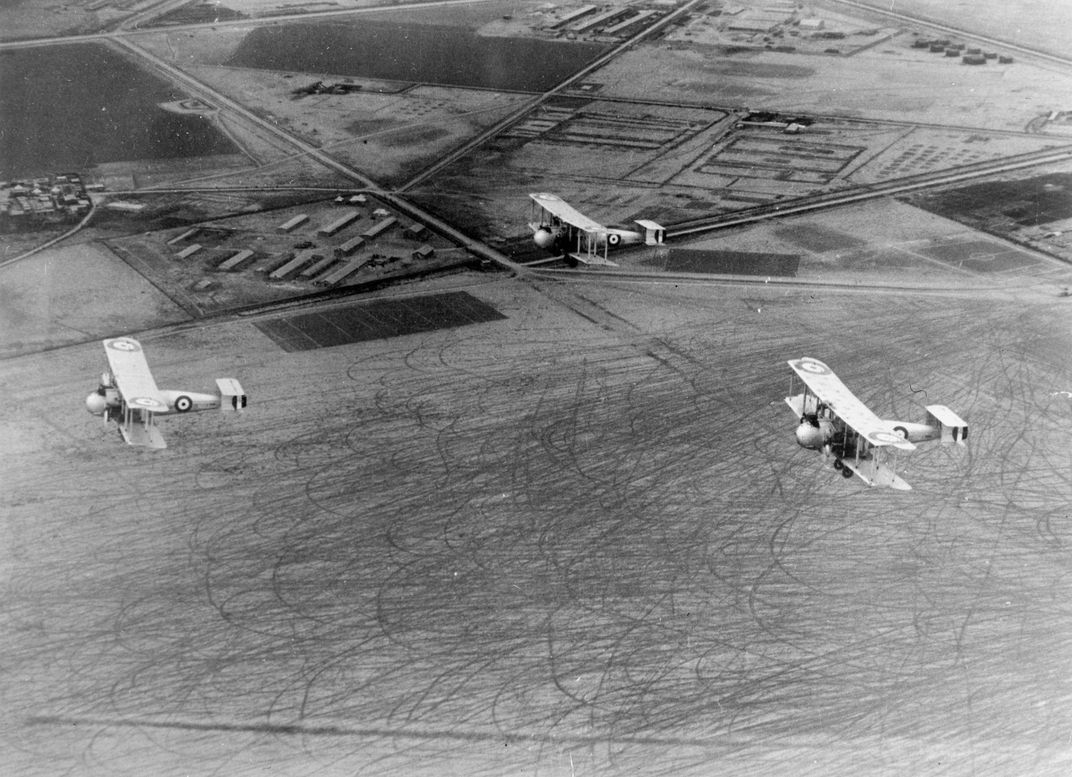

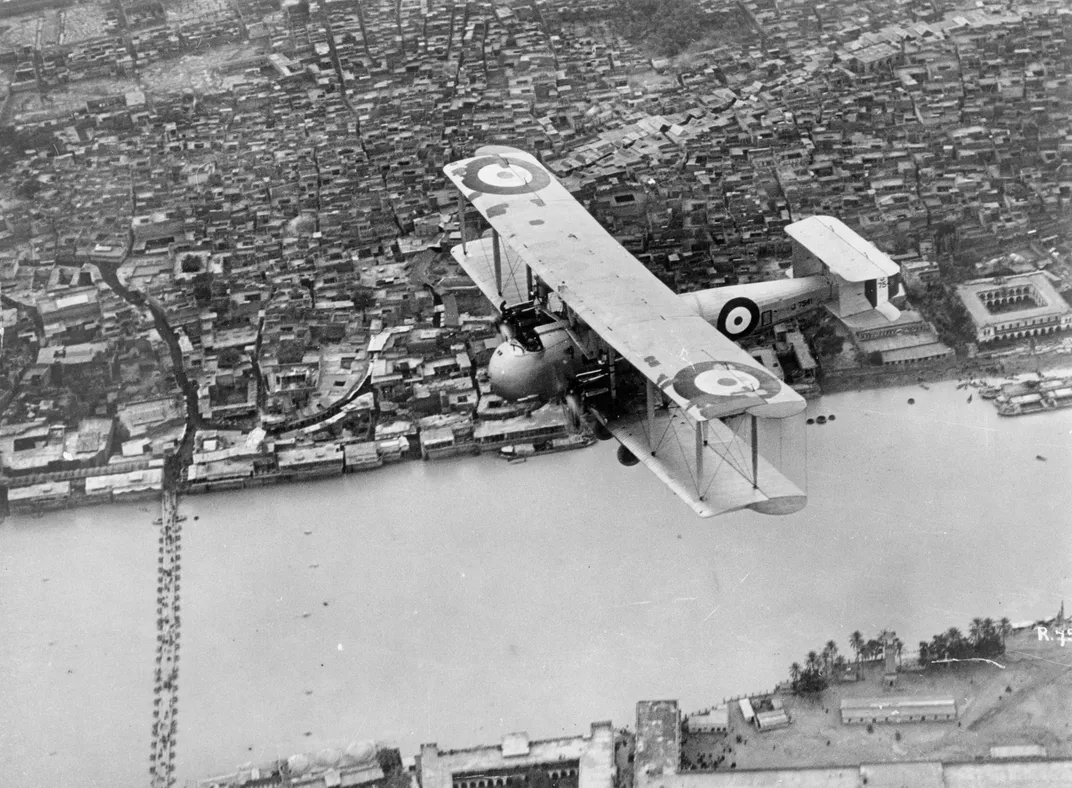

Dawn breaks over the Royal Air Force base at Heliopolis, Egypt, near Cairo. A couple dozen ground crewmen manhandle a massive bulbous-nose biplane out of a hangar. Dogs bark and scurry out of the way as the homely beast is swung into position. A truck pulls up, and men load mailbags and parcels—followed by a few passengers. After a quick check and a hand-cranked engine start, the Vickers Vernon roars off in a cloud of dust. It’s a scene from an unfinished 1924 documentary on the Royal Air Force’s nascent airmail service from Cairo to Baghdad.

In 1921, Winston Churchill, then secretary of state for the colonies, was outraged that letters from London to Baghdad were taking 28 days. Much too slow for running an empire. An airmail line would cut that to under nine, and serve as a critical link in a path extending from Europe to India and eventually Australia. The missing piece was Cairo to Baghdad, 860 miles—and 540 of that was flat hardpan desert.

The job of mastering the daunting stretch of desert fell to the Royal Air Force, which first had to find a way to guide its aircraft over an expanse of unmarked territory. The first 320 miles—Cairo to Amman, in what is now Jordan—had cities, villages, the Dead Sea, and mountains for navigation aids. Flying from Amman to Baghdad, however, would be more difficult. The plateau between Amman and Baghdad was largely featureless save for a 60-mile swath of basalt with two-foot-wide boulders interspersed with bush called camel thorn (strong enough to pierce a tire). Along the way were mud flats: When dry, they were good landing spots, but when wet they could bog an airplane down.

Royal Air Force pilots could have possibly maintained a direct compass heading the entire 540 miles. To go east, they could follow a compass bearing until hitting the Euphrates River, then cross it to the River Tigris and Baghdad. Sounds simple enough, but such a plan wasn’t without risk. Because airplane engines of the day weren’t reliable, airplanes were often forced down, and—at the time—finding a lost aircraft was nearly impossible. The mailplanes would need to be refueled as well, and without some type of visible feature to follow, fuel caches buried in the desert would be overlooked.

The solution—an unsophisticated one—was to simply mark a line along the ground. Pilots could follow it, a downed plane could be found near it, and fuel caches could be placed along it. The first thought was that car tracks might do the trick. The Royal Air Force had armored cars in desert service: Rolls-Royces with raised chassis, oversized wheels, heavy armor, and gun turrets on top. In June 1921, two convoys were dispatched, one from each end of the desert route (they were to meet halfway).

The Amman convoy was made up of 10 vehicles: two Rolls-Royce armored cars, two ordinary Rolls-Royce cars, and six Crossley Motors military vehicles for transporting extra fuel and spare parts. Aerial support, ironically, was critical to the land convoy cutting tracks for airplanes to follow: Pilots would scout ahead for the best route, land, and leave supplies for the ground crew. De Havilland DH-9A biplanes from No. 47 Squadron at Amman and No. 30 Squadron at Baghdad logged 645 hours supporting the desert operation.

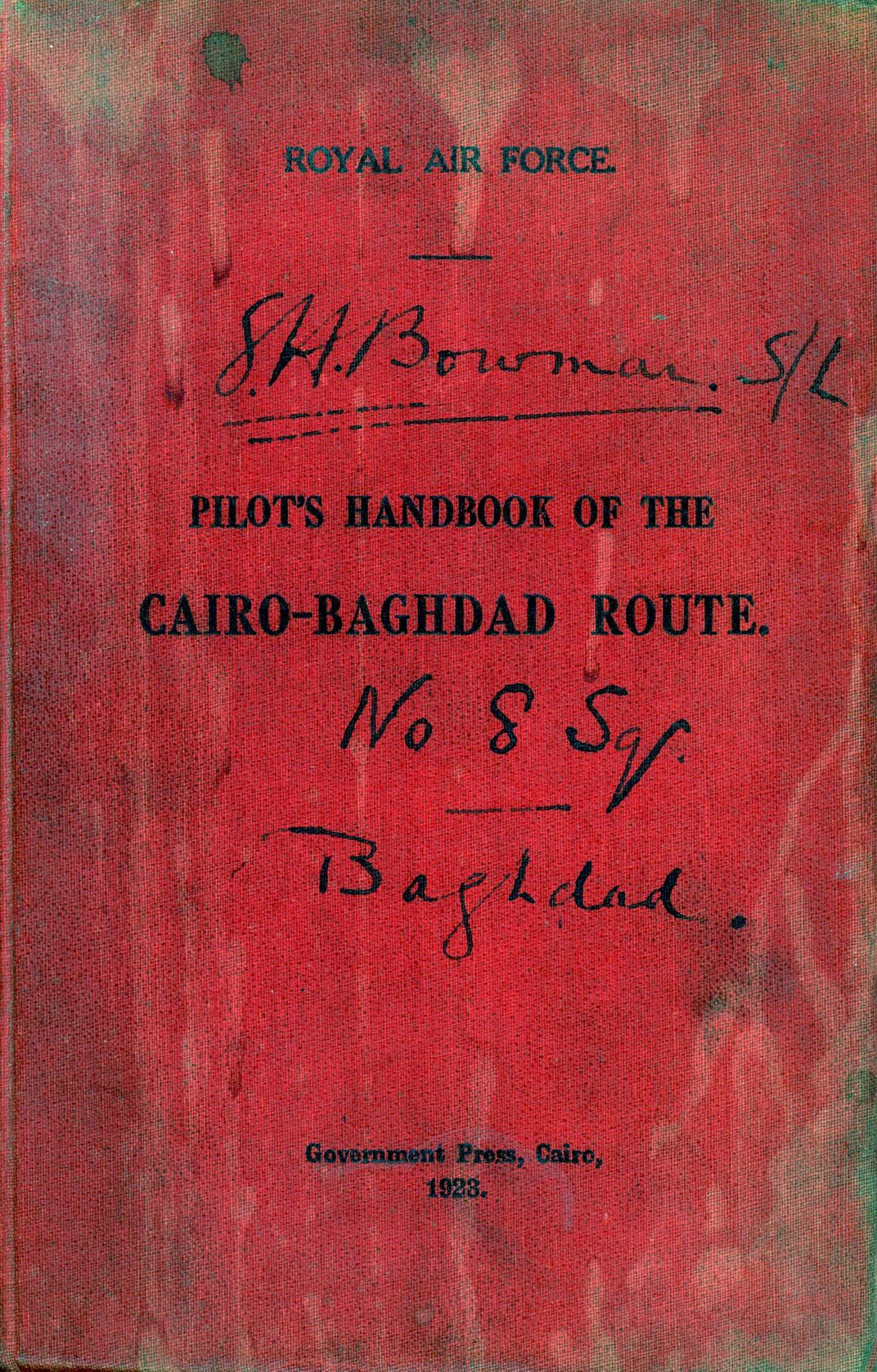

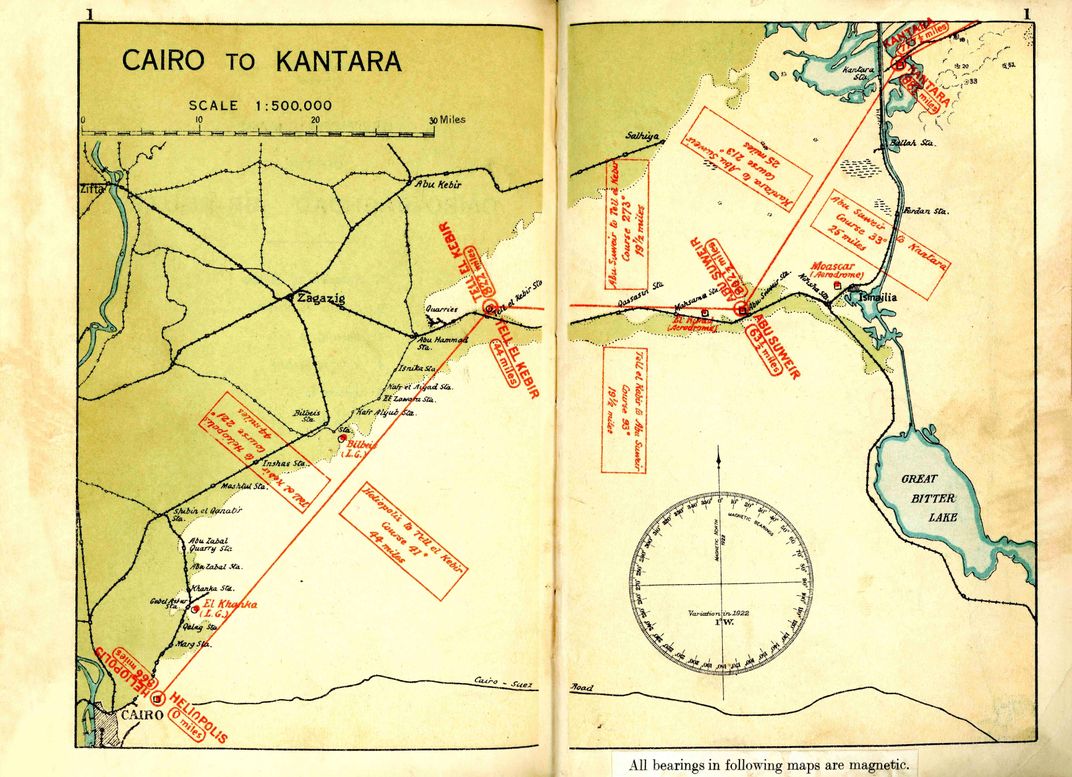

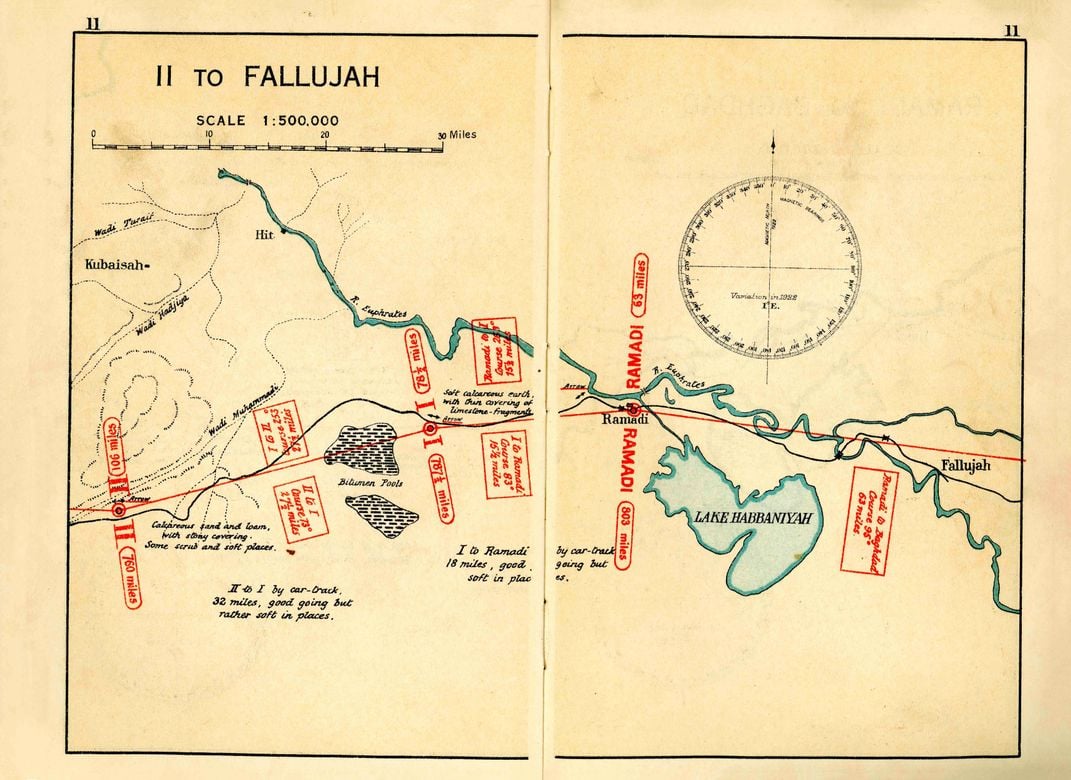

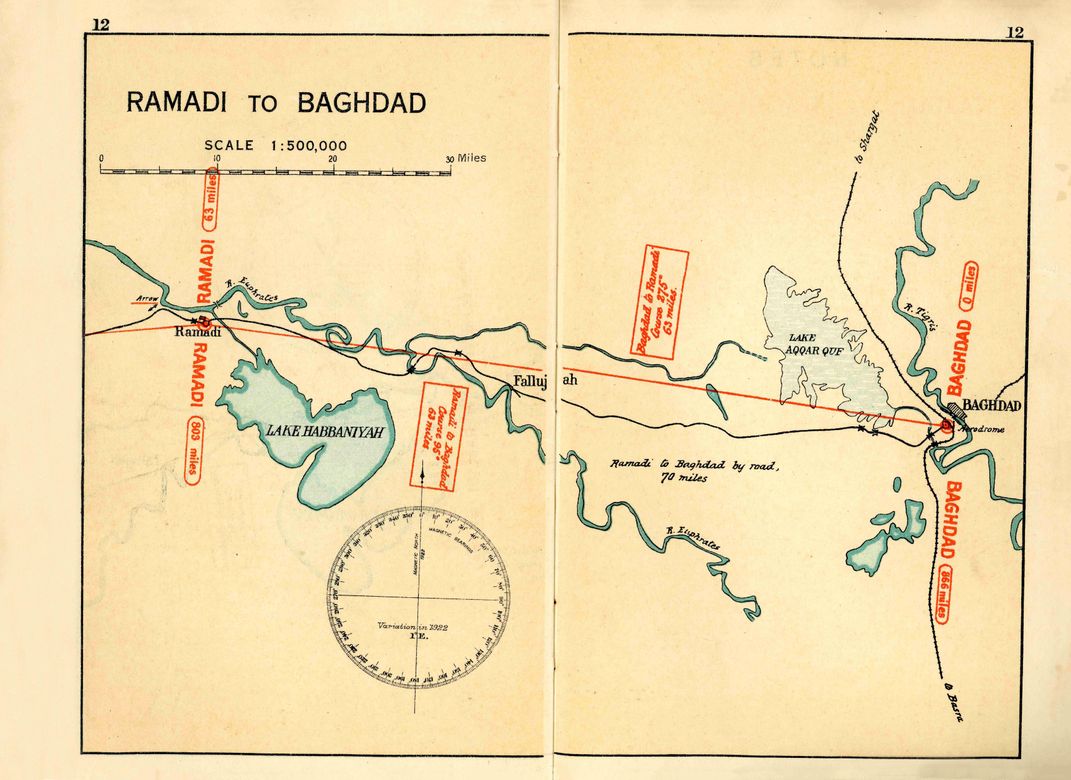

Hampered by the heat, exhausted ground parties surveyed the route as the pilots advanced, recording magnetic headings, elevations, distances, and ground features—such as they were—to generate 12 sectional maps for the Royal Air Force’s Pilot’s Handbook of the Cairo-Baghdad Route.

The maps revealed the route’s few visible features, such as wadis (dried water channels) and the occasional tree. Ground conditions were noted too in case the mailplanes had to land: “soft,” “hummocky,” and “bitumen pools.” The handbook describes how to find permanent water locations: To access one at Bir Kasra Khurana, for example, crews were to “dig to a depth of a foot or two in a valley floor at the foot of a white hill about two miles southeast of the castle ruin.”

Places to land were particularly important. About every 20 miles a spot was cleared of rocks and boulders and marked by a 20-yard circle. In them, the group traveling from Baghdad made Roman numerals from “I” to “XI.” The Amman crew lettered the ground from “A” to “R,” excluding “I” and “Q” so they wouldn’t be confused with the Roman numerals “I” and “Q.” Total landing sites numbered 26. The entire exercise of creating the marked route took six weeks, with the two construction groups meeting at Al Jid (about halfway between Amman, Jordan and Ramadi, Iraq).

Pilots happily followed the etched-out track, but the wind soon swept sand over it. Out came the crews again. This time they took Fordson tractors and excavated a furrow, with large plowed arrows pointing the way. It worked, but some considered the concept crude. Air Vice Marshal Sefton Brancker, after flying the route, deemed it “most derogatory to the training of pilots in navigation.”

June 23, 1921: Launch day. Two-seat DH-9As and three-seat DH-10s made the inaugural flight, but these two aircraft types (both bombers) proved woefully small as transports. More seats and cargo room were needed. The Vickers Vernon soon became the favorite, due to its much larger fuselage, which included an enclosed cabin for the comfort of up to six passengers and for protecting the mail. The Vernons were flown by a crew of four: two pilots, a mechanic, and a wireless operator.

Early trips were ruled by trial and error. Extra fuel strapped under the wings (up to 12 four-gallon cans) added so much drag that on a hot day with less than a full load of cargo, rate of climb rarely topped 100 feet per minute—an anxious experience, with the hills around Amman looming. The Amman aerodrome was soon relocated to nearby Ziza, but the Vernons still needed more robust engines for a better power-to-weight ratio, which improved aircraft performance. Soon new Napier Lion engines boosted the Vernons’ horsepower by 20 percent. Two bronze fuel tanks buried in the desert outside Amman, where the Vernons could land and refuel, eliminated the need for the cumbersome strap-on cans.

With a 75-mph cruise speed, the Vernons required 12 hours (not including refueling stops) to fly to Baghdad. A brisk tailwind might reduce the flying time to nine hours, while a headwind could increase it to 16. For both the pilots and aircraft, it was grueling. “The glare of the desert and the perpetual watching of the track tend to fatigue the retina,” wrote Wing Commander Roderic Hill in a paper presented to the Royal Aeronautical Society on March 1, 1928. Hill, who flew the route from 1924 to 1926, also spoke of the need for refreshment: “We drink some lemonade from a thermos flask and eat some pheasant and ham sandwiches.”

Despite the ruggedness of the conditions, Hill loved the Vernon. In his 1929 memoir of flying the route, he wrote: “It was an extremely comfortable aeroplane for desert flying. If you landed for the night in the desert you could sleep in it, although I preferred to sleep outside under the wings. If it came to pour with rain, you had a little house to go into; if a swarm of locusts bore down on you or camel-flies started to pester you, the thing was to get inside and shut the gauze windows. And so your aeroplane bore you up in the heights during the daytime, and sheltered you by night.” He later commented: “Anyone who can look unmoved at an aeroplane after…a long run must indeed be insensitive to romance.”

But romance was sometimes elusive. “After the winter rains, and in the peculiar lighting of the desert, which has been described as ‘full of things that are not there,’ it is not so difficult to lose the track, especially in low cloud and rain,” wrote Hill. “The weather over the track can be like a witch’s brew.”

Communications, despite their primitive state, were crucial to the venture’s success. Pilots kept in touch with headquarters at each end, letting their commanders know when they had flown past each landing area along the route. Cairo and Baghdad tracked aircraft, which flew in pairs, on large wall maps. If one aircraft had to make a forced landing, it would radio a signal; the other airplane would land beside it and take on the first’s mail and passengers. The downed airplane would then stay and await parts—sometimes an entire engine. Transmitting emergency messages required more than just turning on the radio: When an airplane was in the air, a 200-foot trailing wire antenna had to be carefully reeled out, and when an airplane was on the ground a mast-style antenna had to be raised.

Flying the route exposed pilots to a variety of adventures. On December 5, 1924, Hill wrote in his logbook: “I embarked a cargo of six suckling pigs, loaded them at Ziza. Approaching L.G. ‘F’, the sun was getting low and flooding the desert with a warm orange light and the track was terribly difficult to see. Before ‘F’, I lost it and circled.”

Landing at F, he relaxed and cooked supper on his Primus stove. “I had the cargo of pigs in their crates unloaded and placed by the aeroplane,” he continued. “The inside of the hull stank of them, and they had made a watery mess all over the floor. The temperature was surprisingly warm, and I slept in my valise by the end of my wing. I slept fitfully but peaceably.”

Because of the frequent forced landings, the Pilot’s Handbook devoted many pages to procedures on how best to handle them. The first action was to activate a pistol-fired red flare to signal the forced landing, then release a smoke candle to determine wind direction for a rescue aircraft. The pilot of the rescue craft got further guidance in the form of coded ground panels that indicated the best place to set down. Good judgment in placing the panels was important. “He must not be biased by a desire for the companionship of another pilot,” reads the order, “but must judge strictly on the merits or demerits of the area he has examined.”

There were other things to be mindful of after landing in the desert. A section of the handbook advised how to treat natives, or Arabs, who were said to “generally display a friendly attitude, especially to British personnel.” Offers of food and cigarettes were encouraged, but if “a large body of Arabs insists on relieving you of arms or ammunition, the only course is to give them up with good grace,” advised the handbook, which also provided useful Arabic phrases. Relationships were enhanced by supportive attitudes from air crews. On at least two occasions in 1921, crews assisted Arabs who had been injured in intertribal skirmishes. In July, one was flown to Baghdad for hospital treatment. The locals reciprocated: A group of Arabs aided a mailplane crew forced down 170 miles east of Baghdad by giving them “two skins of their own precious water.”

Beyond their friendly relationship with the locals, the mailplane crews were well equipped for desert living. Necessary supplies included five days’ rations for each occupant; 10 gallons of water for each occupant in summer and five in winter; two blankets for each in summer and three for winter; as well as first-aid satchels, flares, and smoke candles. Pilots regularly flying the route had their own necessities. Hill’s list included a pistol, a brandy flask, a whiskey bottle, cigarettes, tobacco, and tea.

The mailplanes too had their own list of requirements. For the Vernon, the needs included fabric, dope, sewing needles, cables, spark plugs, jacks, pumps, spanners, beeswax, funnels, chocks, prop covers, and more. And when a new engine was needed, 900-pound replacements were flown in and installed on site in the desert. Everyone pitched in: When a takeoff seemed impossible because of the sometimes uneven desert terrain, aircraft were “manhandled into an area where they could successfully get off.”

All of this preparedness, however, came at a cost. With high operating expenses, the Cairo-to-Baghdad airmail route was not profitable. But even if airmail wasn’t a sterling investment from a business standpoint, it was a valuable learning experience for the Royal Air Force. Following World War I, Britain was saddled with mandates for governing Palestine, Transjordan (now Jordan), and Mesopotamia (now Iraq). What better way to police such far-flung territory and keep the peace than with airplanes? The concept was “control without occupation.” The airmail route had taught Royal Air Force pilots the long-distance flying skills, navigation techniques, and logistics needed to conquer vast open geographies.

The Cairo-to-Baghdad run had also groomed several of the pilots for greater things. Hill, promoted to air chief marshal, headed up Royal Air Force Fighter Command from 1943 to 1945. Two other mailplane pilots distinguished themselves: From 1942 to war’s end, Arthur Harris oversaw Bomber Command (and became known somewhat ignominiously as “Bomber Harris”), while Basil Embry led No. 2 Group Bomber Command in 1943, and after World War II became commander-in-chief for Allied Air Forces Central Europe.

Though the Royal Air Force didn’t make money flying the mail, the effort had the effect of waving the British imperial flag. Says the narrator in the 1924 documentary: “Gradually disappearing into the haze of desert heat, the ‘Aerial Royal Mail’ forges another link in that chain of airways which binds our mighty Empire.”

Two years later, however, the Royal Air Force wisely turned the service over to Imperial Airways.