An Aircraft Carrier Worthy of a Superhero

Geoffrey Pyke’s ingenious carrier made of ice was like something out of a comic strip.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/ce/33ce2654-cd75-450e-9cab-11862a36c150/habakkuk-ice-aircraft-carrier-2.jpg)

The Battle of the Atlantic wasn’t going well: In June 1942 alone, 652,487 tons of Allied shipping had been sunk, most of it along U-Boat Alley. At the heart of the battle was the Allied blockade of Germany, and Germany’s counter-blockade. The battle would last nearly six years, and Winston Churchill would describe it as “the dominating factor all through the war. Never for one moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air depended ultimately on its outcome.”

There weren’t enough Allied ships to provide escort, and no air cover over vast amounts of the Atlantic. But inventor Geoffrey Pyke had a plan. What if the British had an aircraft carrier made of reinforced ice?

Pyke’s plan is covered in a wonderful new biography: The Ingenious Mr. Pyke: Inventor, Fugitive, Spy (Public Affairs, 2015), by Henry Hemming. As the author notes, Pyke originally envisioned an iceberg insulated by wood and hollowed out to store military materiel. The top of the iceberg would be leveled off to form a runway, creating a floating airfield. Pyke discovered that ice alone was too brittle; he decided to reinforce the ice with wood pulp. “The ‘berg-ship’ made out of reinforced ice would be cheap to build, and on account of its gargantuan size would be capable of accommodating even modern fighters and bombers. It would measure at least 2,000 feet from bow to stern, making it twice as long as the ocean liner Queen Mary and twice as wide; this would be the largest vessel ever made by man. What was more, it would be unsinkable.”

The concept was considered “both sound and brilliant” by naval officer Lord Mountbatten and Churchill; experiments into the properties of reinforced ice—named “Pykrete” after its inventor—were soon under way. A scaled-down model of the berg-ship was tested on lakes in Canada’s Jasper and Banff national parks.

But by August 1943, the Battle of the Atlantic had changed; weaponry and tactics had improved, aircraft could travel further and, perhaps most important, Portugal allowed the British to operate an airbase in the Azores. These changes, along with the projected costs of the berg-ship, doomed the program.

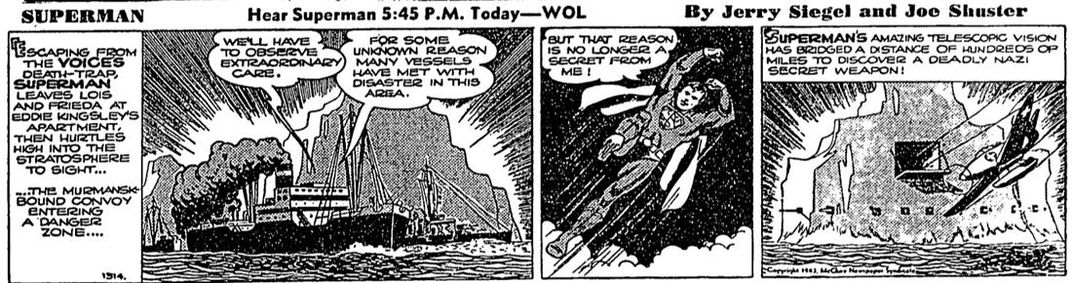

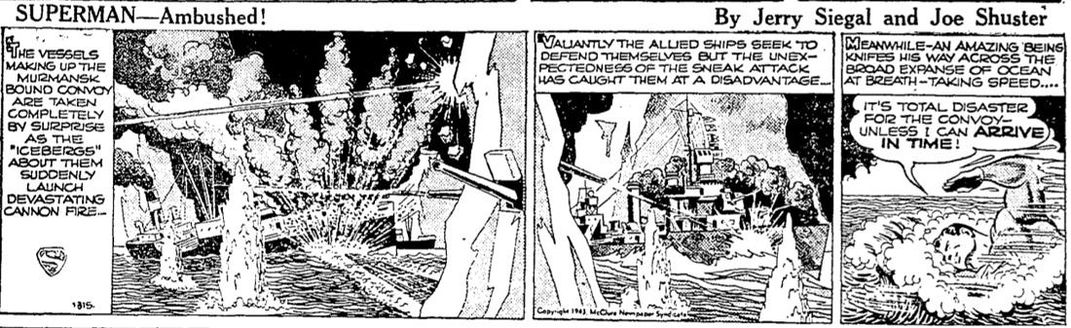

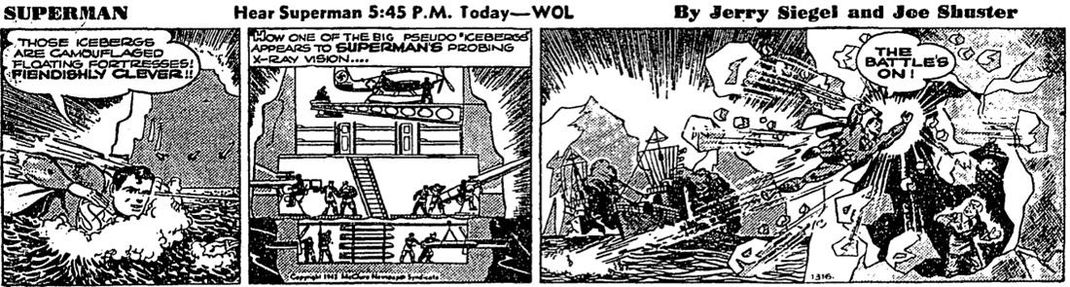

Hemming notes another curious twist: “In late March 1943 an exciting new plot-line had emerged in the Superman daily cartoon strip, then syndicated to newspapers throughout North America and read by millions. Just as the [ice-berg] prototype neared completion, the Man of Steel encountered a strange-looking iceberg.”

Pyke’s discovery of Pykrete was a significant development, writes Hemming, and the results of the reinforced ice experiments “have been put to good use ever since in all permanent constructions (roads, airstrips, bridges, and habitats) in Arctic and Antarctic regions.”