Aircraft That Changed the World

We fearlessly (or foolishly) pick 10

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/10-airplanes-631.jpg)

World changers. It’s almost easier to explain what we don’t mean by that phrase than to define what we do. We have not compiled a list of trailblazers, like the de Havilland Comet, the world’s first jetliner. Nor is this a list of airplanes that represent the greatest advances of aeronautics, such as the experimental aircraft that led to supersonic flight. Rather, we looked for craft that had an impact beyond the realm of things that fly, that reached into the larger culture and touched even those who aren’t frequent fliers or connected to aviation.

Some of our choices are individual airplanes that happened to play a critical role in a world-changing event; others are aircraft types that were so significant in commerce or in war that we could truly say of them: “These changed history.”

We were inspired by the recent book 50 Aircraft That Changed the World, and we could see immediately that authors Ron Dick and Dan Patterson had followed a wiser course: They had picked 50. We could accommodate only 10. We ended up with a list that includes some of those in the book, plus a few of our own.

The most heated debate that broke out in the course of making our selection was also the most revealing; it showed how stringent our standards were—and how subjective. It was over The Spirit of St. Louis. Some editors argued that of course we had to include the airplane flown on the first solo, nonstop trip across the Atlantic Ocean—a trip that made its pilot an international celebrity and inspired a generation to fly long distances, or at least dream about it. Months after the 1927 event, when Charles Lindbergh flew the airplane, a purpose-built Ryan, on a tour across the United States to promote aeronautics, an estimated 50 million people—42 percent of the nation—turned out to see it.

But was it the airplane that people found so inspiring, or the pilot? It’s hard to imagine that journey being completed by anyone other than Lindbergh, but not so difficult to think that he could have done it in another type of airplane. In fact, he had considered an alternative, the Wright Bellanca WB 2.

We’re sure there are readers (more than a few in St. Louis and in San Diego, where The Spirit was built) who will disagree with that reasoning, or with other choices we made. In the end, selecting 10 aircraft from so many possibilities simply became a good excuse to do one of our favorite things: talk about airplanes. We bet you’ll want to join the discussion.

—The Editors

1. Wright 1905

We knew we wanted to start with a Wright airplane, but which most deserved the title of world changer? Wright biographer Tom Crouch, a National Air and Space Museum curator of early flight, nominated the brothers’ third powered aircraft. “The 1905 was the world’s first practical airplane,” he observes.

“The best of the four flights made by the 1903 aircraft at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on December 17, 1903, was only 852 feet in 59 seconds,” Crouch continues. “With that marginal success in hand, the Wrights decided to transfer flight operations to Huffman Prairie, eight miles east of their hometown, Dayton, Ohio. They built and tested two aircraft there, one during 1904 and another in 1905.

“Over the course of those two seasons, the Wrights fine-tuned their design, stretching the aircraft to improve stability and control, enlarging the control surfaces, and improving the propellers. (The same engine, a virtual replica of the one that powered the 1903 aircraft, powered both the 1904 and 1905 models.) On October 5, 1905, Wilbur Wright flew a distance of 24.5 miles in 59 minutes, 23.8 seconds. The brothers had finally achieved their original dream: developing a practical airplane capable of remaining aloft for a significant time and maneuvering under the full control of the pilot.

“The Wrights then faced the task of selling their invention. By the spring of 1908 they had been granted a patent and had signed contracts to sell airplanes to both the U.S. Army and a French syndicate.

“The brothers had not left the ground since the October 5, 1905 flight, however. In addition to brushing up on their flying skills, they had to make their first flights with a passenger, something required by both contracts, and operate a new set of controls necessitated by upright seating, another stipulation of the contracts.

“They pulled the 1905 machine out of storage and modified it with two upright seats and the new control system. They shipped it back to the Kill Devil Hills of North Carolina because they wanted to undertake the test flights in an area with steady winds, soft sand, and isolation from prying eyes. On May 14, 1908, first Wilbur and then Orville took their mechanic, Charles Furnas, up for a ride. These were the first airplane passenger flights in history.”

Crouch’s Museum colleague, early-flight curator and Wright scholar Peter Jakab, concurs with this choice of aircraft: “Even the Wrights did not see the 1903 airplane as the conclusion of their experimental work,” he says. “They had identified the final goal as a ‘machine of practical utility.’ They understood that the 1903 airplane, although embodying all the key technology, was not quite that. When they could stay aloft for an extended period, under the sure command of the pilot, and consistently land safely, they knew they had that ‘machine of practical utility.’ The 1905 machine was that airplane.

“When the Wrights were regularly flying over Huffman Prairie in the fall of 1905,” says Jakab, “that’s when the world truly changed.”

2. Junkers F13

“The F13 was essentially the first aircraft to anticipate the onset of ‘modern’ air transport: cantilever [no wing struts], all metal, low wing, monoplane, streamlined (by the standards of the day),” says aviation historian Dick Hallion, this year’s A. Verville Fellow at the National Air and Space Museum. The metal construction, adds NASM air transport curator Ron Davies, “made it sturdier and less vulnerable to damage than the wood-and-fabric biplanes of its competitors. The metal was especially critical in resisting heat and humidity in tropical countries.”

The F13 first flew in 1919 (as the J13), and by the end of the year was in commercial service in Germany. “It established [founder Hugo] Junkers in a position of global air transport dominance that his firm would not relinquish until the mid-1930s, to Donald Douglas,” says Hallion. The F13 was used in the first airline service in the Americas (Colombia’s SCADTA).

Says Davies, “Unlike postwar transport airplanes that were modified from military types, the F13 was designed to carry passengers in an enclosed cabin. The four cushioned seats had seat belts, and the cabin was lighted and had picture windows.” Now that’s air travel.

After World War I, Germany was prohibited from operating the aircraft, but it sold them or licensed manufacture to 30 countries, including Hungary, Iceland, the Soviet Union, and Japan. In those years, the F13 established air routes in both Europe and the Americas. The last retired in 1948.

3. Boeing 314

In the hands of Pan American Airways, Boeing’s majestic flying boat, the 314, established mail and passenger routes across the north Atlantic, south Atlantic, and Pacific. In Pan Am, An Airline and Its Aircraft, NASM’s Ron Davies writes: “The B 314 flying boat put up all kinds of records, but none could compare with the establishment of the North Atlantic service in 1939 in the epoch-making series of inaugural flights which were, perhaps, Pan American’s greatest contribution to air transport in all its distinguished history.”

On the 314’s Pacific route (San Francisco-Honolulu-Midway Island-Wake Island-Guam-Manila), service was opulent—even the flight deck was described as luxurious—with a lounge, dining area, sleeping berths, and dressing rooms, as well as chefs and china from four-star hotels. Advertisements for the Clippers (named for their nautical forebears) promised an experience that was not just safe but sumptuous, exciting the public about flight.

The 314s were the stars of Pan Am’s fleet for only three years; World War II shut down commercial operations. Still, it was not until the 1960s, with the debut of wide-body airliners such as the Boeing 747, that the B-314s were dethroned as the world’s largest scheduled-use commercial aircraft.

4. The Enola Gay

It was the first use of an atomic bomb: On August 6, 1945, the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay bombed the Japanese city of Hiroshima, killing 70,000 and hastening the end of World War II. (When another Superfortress, Bockscar, dropped a second atomic bomb three days later on Nagasaki, Japan surrendered.) The two missions averted a planned U.S. invasion in which casualties were projected to run into the millions.

The image of those mushroom clouds was unforgettable. For the next 50 years, the nightmare scenario of another attack of such magnitude kept the two nuclear superpowers locked in a tense and costly cold war.

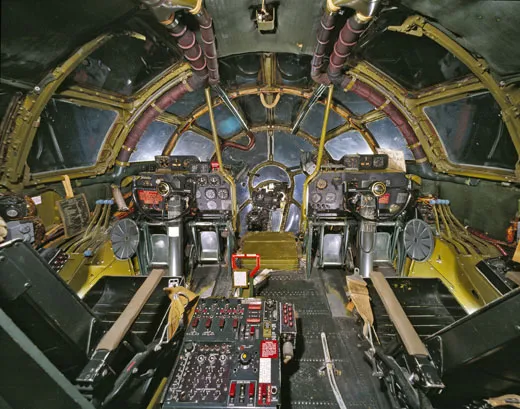

The B-29 was the world’s first nuclear-capable aircraft. It also was the first with a pressurized compartment for the flight crew and the first U.S. bomber with an integrated radar to supplement its Norden bombsight. With a maximum takeoff weight of 140,000 pounds, the four-engine, 11-crewman B-29 could carry up to 20,000 pounds of bombs. It was flown from 1943 to 1954, although the Air Force continued flying variants as tankers until 1978.

Late in World War II, three B-29s made emergency landings (a fourth crash-landed) in Vladivostok, Siberia, after bombing runs over Japan. The Soviets kept them, studied them, and copied them, producing the Tu-4 bomber. Until about 1955, the Tu-4 was the main bomber of the Soviet Union—America’s cold war enemy.

5. Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15

Still a hot-looking airplane 59 years after it entered service, the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 made its mark during the Korean War as the Soviet Union’s first jet-powered day interceptor with a pressurized cabin and an ejection seat.

The MiG-15’s mission was to pick off U.S. B-29 bombers, which led to storied dogfights between the MiGs and the B-29s’ fighter escorts, North American F-86s. Though an improved version of the MiG-15 could climb higher and faster than the F-86, U.S. Air Force pilots generally made up the difference with better aerial combat training. Still, the 670-mph MiG-15 put the world on notice that the Soviets could build cutting-edge aeronautical technology.

“The MiG-15 gave the Soviet air arm legitimacy and lethal potential in the early years of the cold war,” says Von Hardesty, NASM’s curator of Russian aviation history. “The MiG-15 also possessed a certain aesthetic quality: sleek, fast—the very embodiment of what a jet fighter should be.”

Its performance must have reinforced that impression. More MiG-15s —12,000—have been made than any other jet aircraft in history. (Counting licensed versions made in other countries, the number reaches 18,000.) The type has been sold to 43 countries—from Sri Lanka to Cuba to Uganda.

6. Sikorsky S-55

While the helicopter — with its enviable ability to hover, dart in all directions, and land virtually anywhere—had achieved a measure of success in the 1930s and 1940s, it wasn’t until the Sikorsky S-55 made its debut with the U.S. Navy in Korea in 1950 that rotary-wing history was utterly transformed. “For my money,” says Roger Connor, NASM’s vertical flight curator, “though other models pioneered various military and civil applications, the S-55 was the one that saw a real return on the investment put into helicopter development.”

The dazzling success of the S-55—both nationally and internationally—was based on the aircraft’s ability to fill multiple roles: troop and cargo transport, air assault, and casualty evacuation. That versatility resulted in unprecedented demand—1,700-plus were built, more than any previous helicopter type.

The design was brilliant: Sikorsky Aircraft completely reconfigured its earlier layouts to create the first helicopter with a cabin capable of carrying 10 passengers or seven stretchers, and moved the engine to the nose, enabling easier maintenance and solving the center-of-gravity problems previous single-rotor models had experienced. By the end of the Korean War, Sikorsky’s machine had rescued downed pilots, saved the lives of 10,000 wounded soldiers, and delivered escaped prisoners from behind enemy lines.

In addition, the S-55 served as the core of counter-insurgency efforts by the British in Malaya and the French in Indochina, pushing both nations to establish their own aggressive helicopter programs. In American and foreign civil service, the S-55 pioneered helicopter airline transport.

Says Connor, “The accomplishments of the S-55 shifted public opinion—as well as the opinion of military and aviation insiders—from seeing the helicopter as an amusing but not terribly practical curiosity to a necessary tool of the modern age.”

7. Cessna 172

Cessna’s four-seat, high-wing classic is the fresh-faced girl next door: no knockout but a great personality. In 2006, on the occasion of the 172’s 50th birthday, Air & Space/Smithsonian researcher Roger A. Mola wrote, “There’s hardly a pilot flying today who hasn’t logged at least a few hours in a Cessna 172 Skyhawk.” It’s the most successful mass-produced light aircraft ever, with some 36,000 built and still counting, recalling those McDonald’s signs boasting “Billions and Billions Served.”

One flight made the ubiquitous little airplane a world changer. In 1987, Mathias Rust, a young West German, rented a 172 from his flying club and flew it to the Soviet Union, setting down in Red Square in the heart of Moscow, a gesture he called building an “imaginary bridge” (“The Notorious Flight of Mathias Rust,” June/July 2005). Rust reasoned that if he could get through the Iron Curtain without being intercepted, “it would show that [Soviet leader Mikhail] Gorbachev was serious about new relations with the West.” Author Tom LeCompte noted that “Rust’s flight damaged the reputation of the vast Soviet military and enabled Gorbachev to remove the staunchest opponents to his reforms.” Soviet citizens had been told that if they let their military guard down for an instant, the West would annihilate them. “Rust’s flight,” observed LeCompte, “proved otherwise.”

Last year, Cessna announced it will build a 172 Skyhawk TD, for “Turbo Diesel,” that will burn Jet A fuel.

8. Learjet 23

"There were 'bizjets' that preceded the Learjet," says Air & Space founding editor George C. Larson, "but Bill Lear's idea for a smaller and simpler—but fast—aircraft really popularized the idea that businessmen ought to travel based on their own schedules."

The idea of jets dedicated to business travel first found incarnation in the early 1960s, with the introduction of the Lockheed JetStar and North American Sabreliner. Both were spinoffs of military jets. The Learjet likewise evolved from a fighter: the Swiss P16, which never made it into production.

Says Larson, now a senior editor at Business & Commercial Aviation: “The first Learjet was called the model 23 because it was certificated under Federal Aviation Regulations Part 23, for airplanes less than 12,500 pounds, and that made it easier to get through the Federal Aviation Agency’s approval process. Part 25, for heavier aircraft, was way harder. What was wonderful about the Part 23 thing is that the airplane was certificated with a max gross weight of 12,499 pounds. Oh, that Bill Lear.”

The Learjet 23 carried a crew of two and up to seven passengers. It had a range of 1,800 miles and cruised at 485 mph.

Larson notes that the jet succeeded in part because “the company sold the airplanes very effectively, offering to ‘recourse,’ or buy back, an airplane if things weren’t working out for the company that bought it. That brought a lot of individual entrepreneurs and people like [celebrity lawyer] F. Lee Bailey on board.”

The first production 23 was delivered in October 1964. Cost: $550,000. Says transportation writer John W. Smith: “A whole new class of aircraft had been created: the personal jet.”

9. Boeing 747

So magnificent a technological achievement was the Boeing 747 airliner that cultural historians have called it the 20th century’s cathedral. Nearly 40 years after its first flight, it remains, along with the photograph of Buzz Aldrin standing on the moon, the most recognizable symbol of U.S. engineering brilliance. When it was introduced, airports the world over reinforced runways and made other infrastructure changes to receive it.

Still, it is not grandeur or technology or even impact on infrastructure that qualifies it for a place on this list. It was, after all, an evolutionary design. Its creators—Boeing president Bill Allen and Pan American Airways legend Juan Trippe—believed it was merely an interim answer to the demand that airlines would eventually meet with a revolutionary supersonic transport. The SST, they predicted, would relegate the 747 to hauling cargo.

But as wise as those two were, they could not see the future. And what qualifies the Boeing 747 as a world changer is that since it entered service in 1970, 96 carriers around the world have used the wide-bodies to fly 3.5 billion people to their destinations. Consider the impact of all of those trips: the business deals made or altered, the information exchanged, the exposures to other cultures, the families and friends reunited.

10. General Atomics MQ-1 Predator

In November 2002, a vehicle traveling in Yemen and believed to be carrying terrorists was destroyed by a Hellfire missile. What makes the kill historic is that it was executed by a flying robot. The first unmanned aerial vehicle to kill human beings, the MQ-1 Predator has changed the rules of warfare.

Built by General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, the Predator has been operational in Bosnia since 1995 and now is flying missions in Afghanistan and Iraq. The Air Force deployed the latest version, the MQ-9 Reaper, to Afghanistan last October.

The Predator, which has an operational ceiling of 50,000 feet, is flown remotely by a “pilot” and two sensor operators housed in a trailer on the ground. The UAV has a nose camera, variable-aperture TV and infrared cameras, and a synthetic aperture radar to see through smoke, clouds, or haze. The RQ (R for “reconnaissance,” Q for “un-manned”) model flies long-endurance, medium-altitude surveillance missions, while the MQ (“multi-role”) version can carry up to four Hellfire II anti-armor missiles, two laser-guided bombs, and a 500-pound, GPS-guided Joint Direct Attack Munition precision bomb.

Today, the United States and other countries are increasing their use of UAVs for civilian missions, such as law enforcement, border control, and ocean surveillance. Even Hollywood has discovered their potential, putting them to work as movie camera platforms. Here’s an aircraft that has changed not just the real world but the world of fantasy as well.