Airmail Odyssey

Three historic mailplanes commemorated the anniversary of U.S. airmail by tracing the original coast-to-coast route.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/airmail-flash.jpg)

One chapter of American history has everything you could ask for in a national epic: visionary leaders, triumph over technological hurdles, exploration of the unknown, heroes skillfully battling an implacable foe. The action wasn’t directed by the military or by NASA, however, but by the U.S. Post Office. The establishment of airmail service in the United States, 90 years ago last May, is a whopper of a story, yet it hasn’t had the attention that historians and filmmakers have paid to the U.S. space program, say, or the expansion of the West, or World War II. Somebody call Ken Burns.

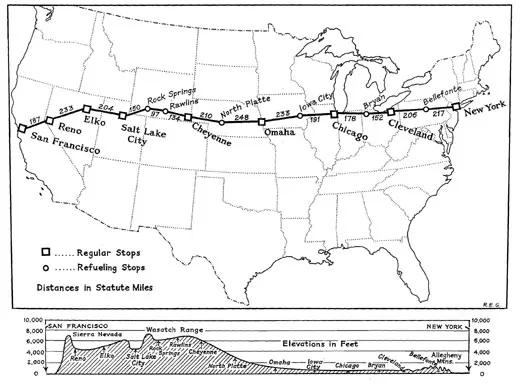

In a way, that’s what Addison Pemberton is doing this week as he retraces the first U.S. coast-to-coast airmail route, flying a mailplane built only 10 years after the first mail flights of 1918. Pemberton will carry 700 envelopes that will receive special cancellations from postal representatives to commemorate the flight. With a daily blog and historical features drawing from Smithsonian archives, this Web site will follow his group’s progress—from the first stop in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, on September 10, to the last stop in San Francisco on September 15.

Pemberton, owner of a Spokane-based manufacturing company, has been flying since he was 15 and is a collector of vintage aircraft. (He has restored 19.) He likes all open-cockpit, round-engine varieties, but his favorites have always been the machines that carried the U.S. Mail. On the reenactment, he’ll fly his Boeing Air Transport, one of the early companies awarded a government contract to deliver mail. It is the great grandaddy of today’s 747s, one of the first aircraft to carry paying passengers along with a load of letters, and key to the Boeing Company’s eventual success. Pemberton’s is the only one flying today.

Two other pilots will fly mailplanes on the cross-country trip: Larry Tobin of Colbert, Washington, will fly the oldest airworthy Stearman biplane, a 1927 Stearman C3B, and Ben Scott will fly a 1930 Stearman 4E Speedmail. (Scott and Pemberton, who also owns a Speedmail, flew the pair on a reenactment flight in 1993 to celebrate the 75th anniversary of airmail.)

Pemberton inherited his enthusiasm for mailplanes from his dad. “My father grew up in Greenfield, Iowa,” he says, “a town between Omaha and Iowa City”—two stops on the transcontinental route the early mailplanes flew. “Every bedtime story I heard had something to do with the airmail.”

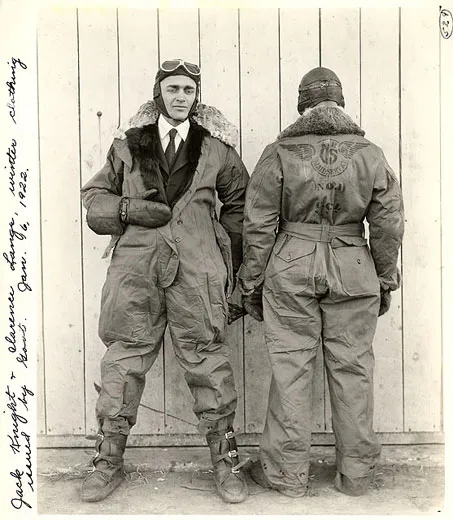

There could hardly be a more colorful crew than the pilots who flew for the Post Office during the first years of airmail. There was Frank Yager, who once flew in fog so heavy that he landed and taxied for 35 miles across the prairie, getting airborne only to hop fences; Slim Lewis, who was said to have been able to fly better drunk than most pilots could sober; and Homer Berry, who, until he got caught, ran an unauthorized taxi business from Laramie to Rawlins, Wyoming by charging passengers $50 to ride in the mail pit.

To get a good idea of the personality types attracted to the job, look at Nathaniel Dewell’s photograph of pilot William “Wild Bill” Hopson, one of the most iconic portraits in American art, or read Dean Smith’s memoir By the Seat of My Pants. Of a two-ship mission he once flew with William Hopson he wrote:

Not long out we noticed a film of ice forming on the struts, wires, and entering edges of the wings; but it built up slowly…. I saw Bill signal that he was going to land, and I followed him into a large pasture.

Since it had taken over half an hour to accumulate that much ice, if we could get the ice off we ought to be able to go another half hour and land again. We found some clubs along the fence row and beat off the ice as well as we could, organized a team to crank our propellers from the inevitable spectators, and took off. It went as planned. Ice slowly formed…, Bill pointed to a pasture; we landed; we hacked off the ice, and soon we were again in the air.

Pemberton’s childhood hero was mail pilot Jack Knight. Of the many courageous fliers, why Knight?

“Because Jack Knight saved the airmail!” Pemberton says. “Jack Knight is the airmail hero.”

Under enormous pressure from Congress to prove in February 1921 that transcontinental airmail delivery was worth the money appropriated for it—that it was consistently faster than train delivery—Knight pulled the first all-nighter for the air service. Having already flown his assigned 248-mile leg from North Platte, Nebraska, to Omaha, Knight volunteered for a second leg, in weather so bad the pilot scheduled for the route refused to fly. Taking off at about two in the morning with only a compass and the conviction that the mail must get through, Knight flew over territory he’d never flown before, lighted occasionally by bonfires that ordinary citizens had set to help show the way. He fought to stay awake, he later told reporters, once trying to fend off sleep “by hammering my own face.” He flew through snow, then in rough air as low as 100 feet above the ground in order to see the railroad tracks he followed into Iowa City. Once there, he spent 10 minutes “dodging steeples” until he located the airfield and landed. He waited two hours for the weather to improve, but, facing a deadline, he took off again at 6:30 a.m. Two hours and 10 minutes later, Knight handed the mail off to another pilot in Chicago. He had been in the air for 10 of the 33 hours it took to make the coast-to-coast run. Aircraft had flown the trip in about a third of the time it would have taken the train. The demonstration secured Congressional funding that would start to build a national system of airway beacons and other enhancements that eventually made possible regular night flights.

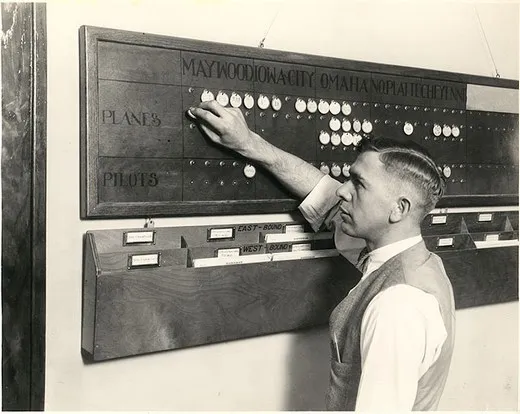

Although Knight’s heroics stand out—and were a turning point for the air service—the conditions in which he flew were typical of what the early pilots faced. Otto Praeger, the man in charge of airmail for the Post Office, knew that the speed aircraft offered was not enough. Congressional and public support would continue only if deliveries became daily and dependable. But Praeger was not a pilot and didn’t understand that a strong will simply couldn’t compensate for primitive equipment and dangerous weather.

In August 1918, the U.S. Army backed away from the mail service, after only three months of flying, because of the tension between the demand for daily service and the impossibility of flying in bad weather. It took another year for the inevitable showdown between Praeger and his civilian force. In July 1919, three days after a fatal crash in rain and fog, several pilots refused to fly from New York to Washington in similar weather. Praeger fired two of them without investigation, and the rest of the pilots went on strike, demanding a hearing. A compromise was reached—one of the fired pilots was reinstated, and future decisions on whether to fly would be made not by Praeger or any another bureaucrat in Washington but by managers in the field—but it did little to decrease the hazards of flying the mail. Thirty-two pilots were killed during their service, most of them in crashes caused by weather.

The Post Office nursed the air mail service through a troubled infancy before handing it off to private companies in 1925. The first eight years saw a number of critical developments: a national system of airway beacons connecting lighted airfields, new navigational aids and more capable airplanes, and a corps of pilots seasoned from years of following now-familiar routes. These are the accomplishments that Addison Pemberton is celebrating this week in his six-day reenactment flight.

“My father used to say that that the mail flights were so regular you could set your watch by them,” Pemberton says. And the mailplane his father saw in the early 1930s flying over Iowa City and Omaha on Contract Mail Route 18 was the Boeing 40.

“I guess that planted the seed,” Pemberton says. In 1982 he visited the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, and saw for the first time the airplane his dad had watched above the Iowa farm. “I studied the airplane for two days,” he says. “It was made of flat stock and round tubes. There were none of the forgings and castings that would have been prohibitive to a small operator like me.”

He came to the conclusion: “I can do this.” That year he started searching for a Boeing 40 to restore; 17 years later, he found one.

When Pemberton and his friend Ben Scott flew their Speedmails from Reno to Iowa City in 1993, they were greeted at stops along the way by anywhere from a hundred to a thousand people. “The amazing thing is that people would bring pictures of family members” who had been on hand when the airmail pilots first connected those cities.

Pemberton expects to see more photographs on next week’s cross-country trip. The photos are likely to express a little of the wonder people felt at the sight of an airplane in the early 1920s, when Charles Lindbergh was not an international celebrity but just one of the pilots who flew the mail. And who knows? Maybe somebody will collect the photographs and make a documentary.

Check back with airspacemag.com beginnning this Thursday, September 11, to follow the pilots’ progress and read more about the history of airmail.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/01.-SI-75-7024~A.jpg)