Airman Down

Rescue aircraft are different today, but “surrender” is still a dirty word.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Air-Down-9-1-2012-13_FLASH.jpg)

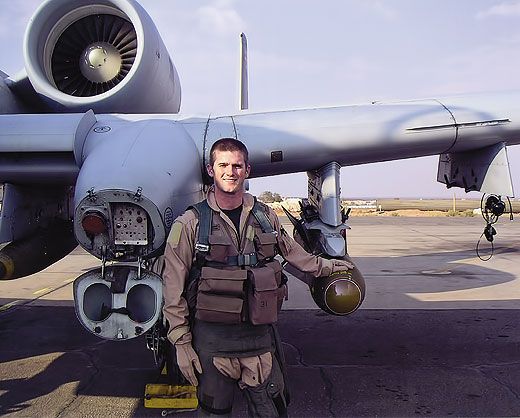

“It’s an ugly, nasty business when airplanes get shot down,” says Lieutenant Colonel Doug Baker. He is the commander of the Operations Support Flight of the U.S. Air Force 104th Fighter Squadron, which has deployed five times since September 11, 2001. At his post outside Baltimore, Maryland, the whine of an A-10C Thunderbolt spooling up saturates the morning air. Baker and his fellow A-10 “Sandy” pilots keep their skills sharp at this Air National Guard base, in view of the flapping flags at Chesapeake Bay marinas, for a hazardous mission: protecting the rescuers of U.S. aviators downed in enemy territory. “I don’t know if Sandy missions are more or less dangerous than some of the other things we do in A-10s,” says Baker, who has flown in Bosnia, Iraq, and Afghanistan. “But they’re done with the understanding that, if it does become more dangerous, we’re still going in anyway. Because it’s worthy of doing.”

The Air Force commitment to locate and extract downed pilots dates to World War II. “A good example would be the First Air Commando group in Burma, operating with light aircraft and covered by friendly fighter forces,” says former Air Force historian Richard Hallion. “The rescue crew, flying a lightplane, would attempt to land at a rough strip of some sort and pull the person out.” The 1944 Burma operation, Hallion points out, also marked the first use of helicopters for search-and-rescue.

The establishment of formal, standardized combat search-and-rescue coincided with the Vietnam War, when U.S. pilots were shot down by the thousands.

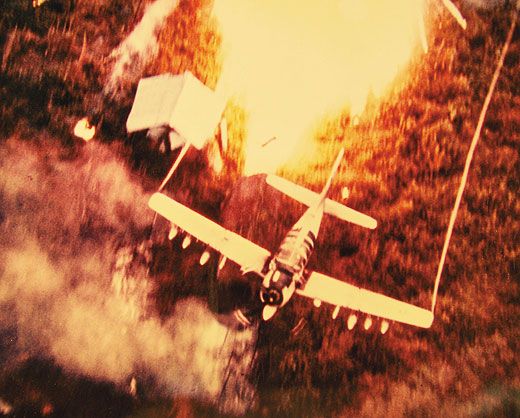

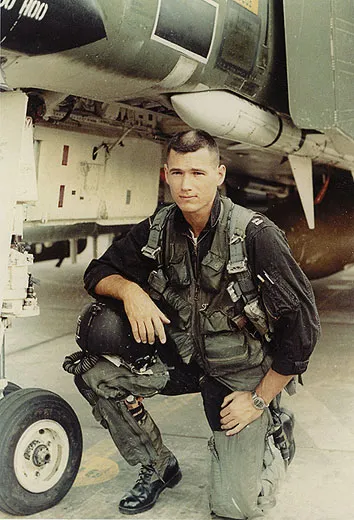

Col. Randy Brandt, U.S. Air Force (ret.), Jan. 9, 2012: On April 6, 1969, I was Dipper One, leading a mission of four F-4Ds against 13 anti-aircraft sites on the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos. At 300 feet above ground level and 550 knots [about 630 mph], I started dispersing [cluster bomb units]. As I pulled up, a Golden BB took off one of my stabilators. The aircraft started to tumble. My backseater and I had a brief conversation like “We gotta get out of here.” The last thing I remember is seeing the blue flame from my ejection rocket taking me out of the cockpit. Unfortunately, the aircraft was inverted when I ejected. There are 65 minutes of my life I can’t recall.

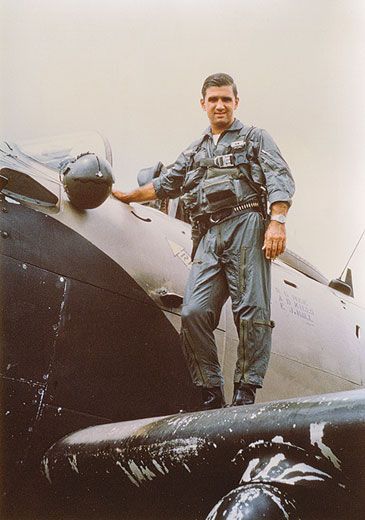

Vietnam also proved the unsuitability of conventional jet fighters for combat search-and-rescue, a mission that requires slow-flying aircraft that can stay aloft for hours. Fast-moving and thin-skinned, jets can loiter over an area for only minutes, take miles to execute a turn, and are vulnerable to ground fire. The answer belonged to another era. Designed near the end of World War II for the U.S. Navy, the Douglas A-1 Skyraider was a prop-driven attack aircraft. Powered by a massive 2,800-horsepower Wright R-3350 engine, the Skyraider had extra armor around the cockpit to protect the pilot and carried 5,400 pounds of fuel to sustain eight-hour loiters above rescues.

If enemy soldiers were closing in on survivors on the ground, A-1 pilots could hold them off with four 20-mm cannon and anti-personnel ordnance carried on 15 weapons stations. “We carried enough stuff to make a hundred passes if we had to,” says John Dyer, who flew 230 A-1 missions in Vietnam, including 42 Sandy flights. (The designation originated with an Air Force rescue pilot based in Thailand whose call sign was Sandy, the name of his dog. Over time, Sandy became a generic term for all A-1 search-and-rescue flights.) Low and slow was part of the job description, “but as long as it was just small arms or 50-caliber type stuff we were getting, the A-1 would survive,” says Dyer.

In 1966, the Air Force began exploring close air support designs that offered greater altitude and speed, as well as deadlier ordnance. The result was the A-10 Thunderbolt. Because the A-10 did not enter service until the late 1970s, “we tend to think of it as a Warsaw Pact tank-killer,” says Hallion, “but the A-10 was actually designed as a replacement for light attack aircraft in Vietnam, specifically the A-1.” Respectfully nicknamed “Warthog,” the single-seat, twin-engine fanjet was designed around a fearsome gun and built to take insult and injury.

Pilots of supersonic aircraft like the General Dynamics F-16 operate with the expectation that they’ll never get hit. “We operate under the assumption we probably will,” says Baker. To survive against the ground fire, both primitive and advanced, that it often encounters in search-and-rescue mode, the A-10 has an industrial-strength superstructure carrying 1,200 pounds of titanium armor plate. The protection “doesn’t make us sexy or fast,” admits Baker, but it gives rescue pilots a degree of confidence. Even more comforting is the Warthog’s most notable feature: its nose-mounted, seven-barrel Gatling gun, with a firing rate of more than sixty 30-mm rounds per second. Should unfriendlies threaten a downed pilot, “that gun solves a lot of your problems,” says Baker.

Capt. Don Dunaway, USAF (ret.), Jan. 10, 2012: I was Sandy Lead at Nakhon Phanom, Thailand, that night. I got my crew to bed early just on the odd chance something might happen. We were called out before dawn. We had an F-4 down. The thing that registered in my mind at the time was that there were some guns out there that managed to bring down an F-4 on his first pass. So they’re either radar-guided or extremely lucky, but they’re big and they’re good.

The 104th comprises six to eight A-10s designated Sandys. You don’t join—you’re selected. In the squadron conference room with Baker (in civilian life, a Southwest Airlines pilot) and Major Paul Kanning, the squadron’s chief of weapons and tactics, you understand why. “Basically, we’re going to throw at you the most difficult problem to solve,” explains Kanning, a veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan missions. “A guy’s on the ground and people are trying to get to him before you can. It’s the ultimate tactical problem for an A-10 pilot. As a result, our Sandy Ones are the best pilots in the squadron, the best problem-solvers, the best critical thinkers.”

In Vietnam, the line-drawing was similar. Some A-1 Skyraider pilots, says John Dyer, gravitated to conventional-strike sorties instead of the highly choreographed combat search-and-rescue missions.

The basics established in Southeast Asia still hold. A four-ship Sandy mission is led by Sandy One, the most experienced pilot, who at a rescue assumes the role of on-scene commander. Accompanying the four-ship flight are two helicopters to extract the downed flier. Also utilized is a high-altitude platform to provide a “big picture” overview—a C-130 designated “King” or “Crown” in Vietnam or today a JSTAR (Joint Surveillance and Target Acquisition Radar) aircraft. For today’s jet-powered A-10s, refueling tankers orbit nearby.

In Vietnam, Dyer says, the coordinated thrusts into enemy territory tended to be “by far, the most difficult, dangerous missions that [A-1 pilots] flew over there.” In one six-week span, Sandys lost six A-1s, one helicopter, two pilots, and a para-rescue jumper.

Brandt: I couldn’t use my right hand. I couldn’t hold the survival radio or my pistol. I found a dead tree, scooped out some of the vegetation beneath it, and crawled underneath. During the night I heard bad guys looking for us. They seemed to be in a line. They’d take 10 or 15 steps, then stop to listen. Hollywood makes the jungle sound like there’s lots of noise at night. Believe me, it’s dead quiet. About five in the morning I came up on the survival radio and they told me: “Sandy is airborne and he’s bringing what he needs.” I could hear A-1s coming. That Wright engine is a very distinctive sound.

The urgency in combat search-and-rescue has not changed over the years. “You’re the fireman waiting at the firehouse for the phone to ring,” says Baker. On five-minute ground alert, Sandy pilots sit in the A-10 on the end of the runway with the auxiliary power unit running or even with engines started. Fifteen-minute alerts necessitate a “hot-cocked” A-10 and a pilot nearby. “You don’t even do a walk-around,” says Kanning. “Somebody’s already done that for you. You just get in the airplane and go.”

For even faster response times, A-10s can fly on alert closer to the action. Orbiting nearby, sipping fuel from a tanker, Sandys get continual threat updates from JSTARs as well as news on the latest successes of the strikes and which aircraft are still airborne. “The alert status will probably be determined ahead of time based on the nature of the threat,” says Kanning. “A lot of time the SPINS will tell you, ‘I need you to sit five-minute alert or 15-minute alert or 30-minute alert.’ ” SPINS stands for “special instructions,” which are part of the Air Tasking Orders issued for a given mission. Special instructions usually include information on mission routing, no-fly zones, and any special operational constraints or procedures.

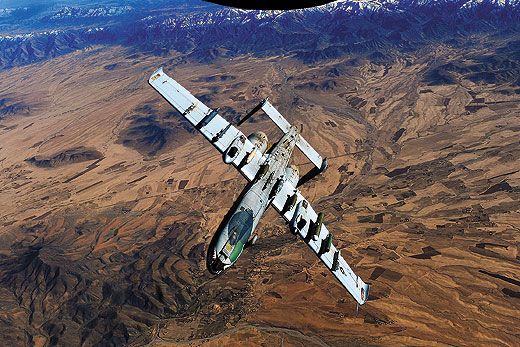

In Vietnam, four Sandys arriving above the rescue split into Sandy High and Sandy Low. The helicopters and Sandys Three and Four occupied a holding pattern, while Sandys One and Two dropped down to locate the survivor and evaluate threats. The low, slow strategy of 1960s-era Sandys has been displaced by 21st century technology. “We stay as high and as fast as we can for as long as we can,” says Kanning. One reason is to avoid “burning the target”—circling close to the survivor, which advertises his position to the enemy. Using sensors, including the A-10’s targeting pod camera and forward-looking infrared, “we can stay literally miles away from the guy and monitor him without having to burn his position.”

Dunaway: We got out there before first light. At daybreak both Randy and his backseater came up on the radio. I used my UHF direction finder to locate Randy, but the backseater’s radio was so sorry I couldn’t get a fix on him. All the time I’m doing this, I’m getting read from Randy about his position, his injuries, and so forth. Randy started hearing noises in the jungle. He said, “You’ve gotta do something. They’re getting close.” For a Sandy, this is really an unwanted complication. You can’t dispense any ordnance until you know where everyone is on the ground, and the backseater was still missing. You try to maintain a calm demeanor. You know, “We’re cool fighter jocks; we don’t get excited.”

Vietnam-era pilots ejected with a pair of simple UHF survival radios capable of transmitting voice and a beacon tone that the A-1’s automatic direction finder could lock on to. The system was not secure: Enemies used captured radios to eavesdrop on the combat search-and-rescue frequencies, and even attempted to impersonate downed fliers, necessitating Sandy crew to pose the survivor an authentication question he had to answer before rescue. Use of the ADF locator often required an A-1 to fly a back-and-forth pattern over the jungle canopy at low altitude, exposed to threats from ground fire.

Air Force pilots shot down today are connected to their rescuers by a robust electronic link. The Combat Survivor Evader Locator (CSEL) in survival vests incorporates a hand-held voice radio with secure digital data transmission capability. With a push of a button, the flier’s GPS coordinates and a choice of macros summarizing his predicament—“injured but can move,” “capture imminent,” etc.—are uplinked in encrypted data bursts over the horizon to satellites, then networked through the military’s Joint Personnel Recovery Center.

Upstairs in the A-10, the Sandy’s Quickdraw interrogator unit enables digital communication with the flier’s CSEL. The Quickdraw first electronically queries the CSEL to verify that it’s really the downed pilot on the other end—“not some farmer who got his hands on the radio and pushed a few buttons,” says Baker. Once the pilot’s identification has been authenticated, two-way, secure data communication proceeds, without disclosing the survivor’s location.

Voice contact always ensues. “There’s some care and feeding that goes with this,” says Kanning. “If he’s injured, you may need to talk him through addressing some of his wounds.”

Downed fliers may be under the most psychological duress they’ve ever experienced. Sandy pilots endeavor to keep them motivated and positive while the rescue plays out. Stressed survivors may be impatient and blunt: Get me outta here! “Absolutely, they’ll tell us that,” says Kanning.

In Southeast Asia, voice contact also introduced the men in the cockpit to the grim reality on the ground, particularly in areas like Laos, where prisoners were often not taken. “A couple of times I actually heard the guy get killed on the survival radio while he was talking to us,” says John Dyer. “One said, ‘I’ve been hit, I’ve had it.’ Then he went off the air.”

Brandt: I told Don, “I’ve got to get my gun.” One thought was in my mind: Most guys who went down over Laos were never heard from. I wasn’t going to surrender. I could hear leaves crunching as they ran right up to me. I stood up at exactly the same time a large boar looked at me. We both jumped about three feet in the air. He did a 180 and took off. I put my gun back in my survival vest and radioed Don: “It was a wild pig.” Don answered, “Just keep talking, Dipper.”

Today’s technology confers a potential element of surprise unavailable in Vietnam. By linking GPS coordinates uploaded by the survivor’s CSEL to the camera in the Warthog’s targeting pod and zooming in, “I don’t need a mirror flash or any signal from you,” says Baker. “I can already see exactly where you are and what you’re doing.” The A-10 is relatively quiet, and above 10,000 feet it may loiter unobserved. “We may be able to kick in the door and come get you without the enemy even knowing we were there,” says Baker.

Until the Sandys arrive, other eyes in the sky can watch over a downed flier. A remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) such as a Predator drone can loiter overhead for a lengthy period, observing with its cameras. While the RPA operator maintains contact with the Joint Personnel Recovery Center, the operator can also talk directly to the survivor via radio. If necessary, an armed drone could provide cover against approaching enemy forces.

All of this assumes suspension of Murphy’s Law. “You have all these toys, but you have to go out the door assuming none of this stuff is going to work,” says Baker. Sandy pilots still train to do it the old-fashioned way: “the survivor popping smoke, and us flying down and taking a look at him,” says Baker.

In Vietnam, taking a look required daylight. Sandys operated only from dawn to dusk. If rescue couldn’t be achieved by sundown, the survivor was “put to bed”: issued advice on overnighting in the jungle. Today, “we prefer to do everything at night,” says Kanning. The advent of night-vision goggles and forward-looking infrared cameras has made darkness a powerful ally of combat search-and-rescue operations. While night-vision capability is still uncommon among enemy forces, Baker has flown with night-vision goggles for 15 years. Aviator survival kits include infrared strobe beacons visible to rescue pilots wearing night-vision goggles; the strobe beacons are also visible to most of the infrared sensors on U.S. aircraft, so most of the supporting rescue aircraft can see the strobe. The A-10, like most U.S warplanes, has been modified for night vision by making cockpit instrumentation NVG-compatible.

Dunaway: Everyone involved in the effort was listening when Randy came up on the survival radio and said, “Disregard about those last noises in the jungle.” The sigh of relief must have registered about a five on the Richter scale. As a Sandy, ground search parties were always in the back of your mind. It might be only small arms, but once you pinpoint your survivor and talk to him, you have to suppress that resistance before you even think helicopters.

Unlike Skyraiders, A-10s can’t fly slow enough to shepherd the helicopter, usually a Sikorsky HH-60. In Vietnam, a single chopper, the Sikorsky HH-3 “Jolly Green Giant,” was escorted to the pickup point at 140 mph by a trio of A-1s. The remaining Skyraider, Sandy Four, protected the backup helicopter. Enemy forces often held fire until the helicopter arrived; the rescue ship was a bigger prize than one downed flier. Once an HH-3 was hovering and the A-1s circling, “I can’t even tell you how many AK-47s opened up,” says John Dyer.

Dyer’s son, Major John Dyer Jr. of the 104th Fighter Squadron, who recently returned from Afghanistan, is a second-generation Sandy. In his experience, although the unfriendlies try to reach crash sites as soon as possible, when the A-10s arrive, they disperse. “What we’ve seen from those guys is, they prefer to disappear,” says Dyer Jr. “One of the lessons they’ve learned is that the weapons we bring are pretty precise.”

Dyer Jr. and his fellow A-10 pilots fly a racetrack pattern much higher than his father did in the A-1. Small arms, therefore, are less menacing to his A-10 than they were to the Vietnam-era Sandys. Says Dyer Jr.: “We’ll generally stay above it all—unless the guy on the ground really gets himself into a jam.”

Ground fire of any caliber directed at A-10s during a rescue is answered in what Doug Baker terms “a graduated, aggressive manner.” Level one, firing the nose-mounted 30-mm cannon, is “knock it off.” The next level is the deployment of high explosives.

Dyer Jr. usually knows a number of things about threats awaiting him. “Before we even stick our nose into where the survivor is,” he says, “ideally, we like to have a JSTAR give us a detailed picture first.” The long-range aerial radar platform detects vehicles, weapons, and troop movements on the ground.

A survivor awaiting rescue has input into his own defense. Under imminent threat, he may request fire from the A-10s. Rules of engagement govern response. A search party of armed soldiers is an obvious target. But what about an anonymous pickup truck speeding in the general direction of the downed airman? “We train for that,” says Baker. “He’s threatening us just by being in the wrong place at the wrong time.” When in doubt, Sandys opt for warning shots from the Warthog’s revolving cannon. A hundred rounds on the road in front of the driver of the pickup, Baker suggests, may persuade him to take a different route.

Brandt: I heard Don say, “All clear. Jolly in.” Don and his wingman were flying directly over me. I could hear the rotors of the CH-53 but I couldn’t see it. Don said, “Pop your smoke grenade.” When the Jolly got overhead, his rotor wash literally leveled the jungle. They let the penetrator down on the cable and I put my arms into the straps. I’m going up the hoist, and the two 7.62 mini-guns up in the chopper are spraying the jungle all around me. The engineer and a para-rescue jumper in the Jolly grabbed me and unceremoniously threw me inside. As we’re egressing the area in the chopper, I heard Don say on the radio, “Good job, everybody. Happy Easter.”

The art of plucking a survivor off the ground changes with the terrain of war. Due to thick jungle canopy, Jolly Green Giants in southeast Asia lowered a heavy, pointed forest penetrator on a cable and winched the survivor into the chopper. Today’s helicopter pilots prefer, whenever possible, to land to retrieve airmen. It’s faster and minimizes hovering, a risky phase of flight that renders the helicopter and the flier on a cable vulnerable to ground fire.

Once the survivor is on board, “it’s get out of Dodge,” says Baker. Flying an exit heading plotted in advance, the chopper leaves the scene preceded by an A-10, with two more circling overhead. John Dyer says the egress was even more defensive in Vietnam: One A-1 directly underneath the helicopter and one on each side. “We used the heavier armor of the A-1 to shield the chopper from ground fire,” he says.

Dunaway: We’re down there in the treetops in the A-1s. After they reeled Randy in, I asked the Jolly to search for the backseater. We maintained a close daisy chain around the helicopter in case I’d made a bad call and there was resistance. It didn’t take long to find him. We had a route picked for the helicopter to egress the area safely and gain altitude. We turned them west toward [the air base at Nakhon Phanom, Thailand], then handed them back over to their escort. We all headed home together.

“Just like the A-1 guys, there’s a mentality in the A-10 community that we’re gonna do this job and we’re gonna be good at it,” says Kanning. In a subdued tone, Baker underscores the factors inherent in accomplishing that: “Are you going to be able to get this guy back in one piece? Are you going to lose more people trying to get him back? It’s very difficult. It’s not something you jump up and down about doing if you have to go do it for real.”

Would Sandy pilots consider scrubbing a precarious rescue and instead advise a downed airman to surrender? Their reply: Never.

Frequent contributor Stephen Joiner writes about aviation from his home in southern California.