America the Cruisable

The seaplane Glenn Curtiss designed in 1914 may have had trouble on the ocean, but its reproduction is delighting a whole town on a lake.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/curtiss_631-mar08.jpg)

For aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss, the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York held a special appeal. "Curtiss was fascinated with getting off the water," says Trafford Doherty, executive director of the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport, Curtiss' hometown, located at the south end of Keuka (pronounced "CUE-ka") Lake. In 1908, there were no airports, so an aircraft that could take off from and land on water would be far more versatile than a land-based airplane.

Doherty, a former pilot and production control specialist for the Schweizer Aircraft Corporation in nearby Elmira, is a genial tour guide. As he prepares the museum for a banquet celebrating the fifth annual Seaplane Homecoming Weekend, he points out artifacts and exhibits attesting to Curtiss' inventive genius: bicycles, motorcycles, engines, a house trailer, and of course airplanes, from an early "pusher" (with the propeller facing the rear of the aircraft) through the famous JN "Jenny" series to later models, including an Oriole and a Robin.

By 1911, when Curtiss perfected the technology needed for seaplane operations, he had already earned the title "Fastest Man on Earth" by powering a motorcycle with a V-8 engine he built and driving it at 136 mph. He'd also made the first pre-announced public flight in the United States (earning pilot license number 1 from the Aero Club of America), won the first international air race (earning pilot license number 2 from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale; Louis Blériot held number 1), and made the first long-distance flight between two U.S. cities by flying from Albany to New York City. To overcome hydrostatic friction—a suction-like force that prevents seaplane hulls and floats from breaking free of the water—he invented the "step," an angled break on the bottom of hulls and floats that enables the seaplane to rise from the water. The step is considered his most important contribution to the science of water flying. First perfected on the 1912 Model E (considered the world's first successful flying boat), the invention earned him a prestigious Collier Trophy for the second time in two years (the first was for the invention of the "hydroaeroplane"). In the meantime, he was making his hometown arguably the aviation capital of the world. Says Art Wilder, a retired mechanical engineer and director of the museum's restoration shop: "There was more done in Hammondsport between 1908 and 1914 than in any other period I've ever studied in aircraft history."

Tourists may know the Finger Lakes region more for its wineries than for the achievements of its favorite son, but on an overcast day last September, the visitors were well aware of Glenn Curtiss' work. They had come to see the museum's reproduction of Curtiss' 1914 flying boat, the America, make its maiden flight. The event has been on calendars far and wide. "We came all the way from Virginia for this," said Joyce Miller, standing with her husband, Hugo, who wore a T-shirt reading "Wilbur and Orville who?"

It took three years to build the America reproduction. In 1999, the museum's restoration shop volunteers completed and flew a reproduction of a 1913 Model E flying boat, and in 2004, they completed and flew a reproduction of the A-1 Triad. The Navy purchased the original A-1 in 1911—the service's first aircraft. (This, combined with the fact that Curtiss trained the Navy's first pilot, earned him the title Father of Naval Aviation.) But the museum considers the America in some ways a more significant aircraft. It incorporated counter-rotating propellers and an enclosed cabin, and it was the first flying boat with multiple engines—two, initially, then three. And, with a 72-foot wingspan and an empty weight of 3,000 pounds, it was mammoth. "Compared to other U.S. aircraft, the America was like Starship Enterprise," Doherty says.

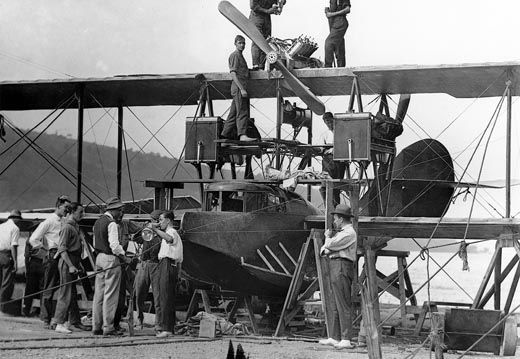

The America was built to compete for a $50,000 prize offered by the London Daily Mail for the first transatlantic crossing by a flying machine. Rodman Wanamaker, a son of the Philadelphia department store founder John Wanamaker, commissioned the construction, giving Curtiss $25,000 to build what became the Model H Boat, the Curtiss-Wanamaker America. Wanamaker intended the flight to double as a centenary salute to 1814's Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812, and he wanted a Brit and an American to share the honor. Cyril Porte of the Royal Navy was named pilot, and George Hallett, a mechanic and Curtiss employee, was copilot. Both men were present on June 22, 1914, when the America was christened at Hammondsport before an audience of 2,000. One of Hallett's challenging jobs was changing spark plugs in flight (plugs didn't last long back then). One wonders how he felt about the prospect of doing so in rough air, bad weather, and evening darkness.

In the summer of 1914, the America underwent extensive testing. Barely a month before the flight was set to launch, World War I erupted. Porte was recalled to England and the flight put on hold.

More than 50 years later, Hallett, in his memoirs, reflected on the scrubbed mission: "At that time none of us believed we could not have made the flight successfully, but looking back on it, after some years and much experience, it seems to me that we could not have made it." Hallett concluded that the lack of a carburetor heating system, vibration capable of shaking loose engine cooling lines, or airframe icing would have doomed the flight. (The aircraft that finally made the first flight across the Atlantic was also a Curtiss-built seaplane, the NC-4, the only one of three NCs that made the 1919 attempt.)

The British military bought the America and a second Model H for its patrol aircraft development program, along with a score of H-4 Small America flying boats. Neither Model H survived. "They weren't lost in accidents," Doherty says. "They were tested to destruction. It was a harsh environment, and seaplanes tended to have short service lives."

But the basic hull design survived, adapted for the United Kingdom's larger coastal and anti-submarine patrol aircraft of World War I, starting with the Felixstowe F-1. Curtiss developed derivatives and sold them to both the U.S. and Imperial Russian navies. And the America lived on in the hulls of aircraft from Pan Am's Boeing 314 Clippers to PBY Catalinas to Howard Hughes' one-flight wonder, coincidentally also designated H-4. One has only to compare the broad, keeled bottoms of the America's descendants with the jowly sponsons projecting from the America hull to see the family resemblance. "All the great flying boats of the world have bloodlines [reaching] back to this one aircraft," says Jim Poel, a former airline captain, owner of a Republic RC-3 Seabee amphibian, and pilot of the reproduced America.

No complete set of blueprints for the original America exists. The museum based its reproduction on partial plans, photographs, and records of construction materials. The frame is ash and Sitka spruce; the wing ribs are pine. Like the original, the craft is painted dark red. Instead of the animal glues and silk Curtiss used to cover his Model H, the re-creation team used Polyfibre, a synthetic aircraft fabric, similar to Dacron.

Once completed, the reproduction was disassembled into three major sections, which were trucked half a mile to the lake and put back together. At the start of last September's Seaplane Homecoming Weekend, the flying boat sat atop a small gantry mounted on a pair of rails leading into the water. As the hour of launching neared, a crowd grew. The sky was overcast, making the day reminiscent of the black-and-white photographs documenting the original christening. Some onlookers gazed with the same curiosity seen in those old photos: Will this thing really fly?

Doubts were understandable. The original America was powered by two 90-horsepower OX-5 V-8 engines. Because the reproduction was 500 pounds heavier, the team decided to use vintage OXX-6 100-hp engines, which were sent out in 2006 for an extensive rebuild; the revisions included a new water pump for the counter-clockwise engine, plus new camshafts, valves, and valve springs for both. But the engines weren't ready for the September flight, so the restorers substituted the OX-5s.

Up close, the craft looks less aero than nautical. The sponsons give it the appearance of a hydroplane, a boat with winglike structures that enable it to skim the surface of the water at high speed. The cabin looks more like a pilot house than a cockpit, and the primary navigation instrument is a large ship's compass. While remaining largely faithful to the original, the reproduction has a digital engine monitor, and trim tabs have been added to the jumbo-size elevator and vertical stabilizer to reduce the forces needed to control it. "Basically it's very heavy," says Poel, who flew the museum's previous reproductions. "It will take a lot of force to move the controls."

In the early afternoon, seaplanes paraded around the south end of the lake before performing a flyover, circling Curtiss' grave at the Pleasant Valley Cemetery. Then, the America was eased into the water and towed to Depot Park, just down the shore, for christening. A crowd estimated at 3,000 awaited its arrival, and a half-dozen Grumman, Republic, and Cessna amphibians were arrayed around the adjacent beach in welcome. Museum volunteers in period costumes portrayed a welcoming committee to reenact the christening. Jim Poel, copilot Lee Sackett, and Orren Baisch (as Glenn Curtiss) stood in for the original christening party, with Poel's wife, Lovada, representing Katherine Masson, the daughter of a local vintner, who in 1914 was selected to christen the big flying boat. Then the reborn America was pushed off the beach and turned lakeward, the OX-5s were propped by hand and fired up, and the aircraft taxied out.

Word had been circulating since morning that the America was not quite ready to fly. Though the hull rode in the water at the same level seen in photos of the original, during water taxi tests conducted in the last few days it was not getting up on the step. "We sort of make the same mistakes Curtiss did, even though we know a lot more about aerodynamics," Poel says philosophically. "We still stumble along, and then we realize: That's what he was doing too."

"One of our friend's dads used to work with Curtiss, and he said a lot of things they tried didn't work the first time either," Wilder says.

In the end, it didn't seem to matter to anyone that the America didn't fly that afternoon. The crowd watched this visitor from another era turn grand circles in the water, leaving big, frothy plumes behind. "That's the way it goes," said Jim Flieg, an industrial engineer from Potter, New York, who came to see the America with his father, John, and son Joshua. "I work on machinery. And when someone's been working on something and they flip the switch and it actually does something, I'm thrilled."

"We've re-created a moment in history here," Poel said after bringing the America back to the shore. "And to see it taxi around and to hear two OX-5 engines is something not many people get to experience."

The America is back on display at the museum while efforts to overcome its hydrostatic friction continue, mainly by finding ways to reduce weight. Another area under study is finding a stabilizer incidence angle relative to that of the wing that produces optimum lift. The team is also tweaking trim and rigging. And soon the more powerful OXX-6 engines will be installed. "We'll work on engines and propeller combinations and do some serious thrust measurements that we haven't done before," Wilder says. The America's first flight, anticipated to be made this spring, will likely be a quiet occasion, Doherty says, with the public debut planned for the next Seaplane Homecoming in September.