A Brand New U.S. Weather Service Joined the Race in 1878 to Observe a Solar Eclipse

The event gave the American scientific community a chance to prove themselves. A new book tells the story.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/ed/97edc150-dbf3-495a-8781-cbc05a7176d8/signal_station.jpeg)

In August, millions of Americans will have the opportunity to travel with relative ease to see one of the greatest astronomical events humans can observe: a total solar eclipse. It’s going to be a mess for anyone choosing to hop in a car and head to the path of totality that morning, but the worse you’re likely to experience is a mammoth traffic jam and too-long stretches between bathroom breaks. The challenges were phenomenally different nearly a century and half ago, when another eclipse promised a show on our continent, traversing a southeasterly path from the Idaho Territory—the state had not yet been admitted to the Union—down to Texas.

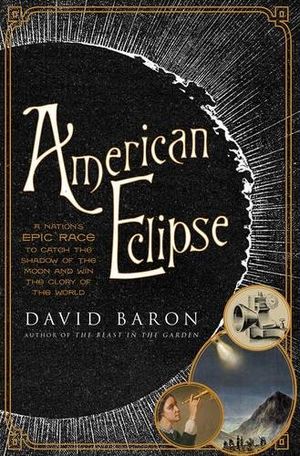

A new book by David Baron, American Eclipse (Liveright Publishing, June 6, 2017), documents the “epic race” by several scientific groups to observe the July 22, 1878 event. At the time the American scientific community was not yet highly regarded overseas. By the time 1878 rolled around, with the Civil War and Reconstruction behind them, several Americans were determined to change that. Thomas Edison, who was just beginning to make a name for himself with the phonograph he invented a year earlier, James Craig Watson, who turned asteroid-hunting into a personal battle with a European astronomer, and Maria Mitchell, the first American female professional astronomer, were among those who packed up thousands of pounds of supplies and equipment and headed into the western territories to make observations of the sun—and help put the United States on the scientific map.

The thing about an eclipse, of course, is that you need clear skies to see it. And if you want to know where the skies are most likely to cooperate, you need a weather forecast. As Baron writes in American Eclipse, the 1878 eclipse hunters were in luck. The very thing they needed had been developed just in time for the event: The nation’s first weather service.

The telegraph made such real-time storm warnings possible. The Smithsonian [Institution Secretary] Joseph Henry, whose electrical research had paved the way for Morse’s invention, took an initial step toward that goal in the 1850s. He arranged for an assemblage of telegraph stations each morning to wire local weather conditions to Washington, where the information was posted at the Smithsonian (using colored cards on a large map) and published in the newspaper. The continually updated chart gave a general sense of storm systems moving across the country, but Henry’s institution did not issue formal forecasts. The federal government did not take on that responsibility until a decade later, when a nascent weather service rose from the ashes of the Civil War.

The Union Army’s Signal Corps had made a name for itself collecting intelligence on Confederate troop movements and sending coded messages back to commanders using, among other methods, the telegraph. When the war ended, the head of the Signal Corps, General Albert Myer, lobbied for another mission that would use these newfound skills. “On February 9, 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant signed legislation creating America’s first national weather service. It would be operated by the Army Signal Corps.”

Meanwhile, an astronomer named Cleveland Abbe was struggling with his work at the increasingly dilapidated Cincinnati Observatory, in a city becoming more industrial—and polluted—by the minute.

Cincinnati—dubbed Porkopolis—was a booming city of meatpackers and brewers, and thick smoke often blanketed the sky. Since atmospheric conditions dictated how much one might see through a telescope, Abbe grew interested in meteorology, and he devised a plan to track the weather in Southwest Ohio. With the help of observers who telegraphed data from a broad geographic region, Abbe drew up daily forecasts—he called them probabilities—and, beginning in September 1869, he offered the service to area newspapers and private subscribers. For his efforts, this fledgling weatherman, though thirty years old, earned a fondly geriatric nickname: “Old Probabilities,” or “Old Probs.”

Cleveland Abbe had created something historic—the first regular weather forecasting service in the United States—but within a year the chronically cash-strapped Cincinnati Observatory was forced to abandon the venture, and Abbe too was soon dispatched, placed on unpaid leave. General Myer, just then seeking to create a weather service on a national level, called on Abbe for advice and quickly offered him a job as his chief meteorologist.

At the weather service, Abbe was making a name for himself, but he wanted to do more than forecast, and began to argue that the agency should pursue meteorological research as well. Then the eclipse hunters came calling.

What [the eclipse hunters] required was not, strictly speaking, weather forecasting; there was no way to predict the movement of high- and low-pressure systems several months in advance. The task was simply one of compiling and analyzing historical data. Abbe identified thirty-six weather stations that fell within the computed path of the moon’s shadow, and another thirty-one that sat just outside. He gathered statistics for the months of July and August over the previous years, and he then calculated the odds of clear skies on the afternoon of July 29. According to Abbe’s math, the region around Rawlins, Wyoming, should enjoy a 79 percent chance of favorable conditions at the time of the eclipse. At Denver, the numbers were less optimistic, but he still calculated better than even odds of a clear view, at 60 percent. The Signal Service issued these figures, and many others, in a circular that it distributed to the government and the press.

But Abbe, the frustrated astronomer, aspired to do more than provide advice; he hoped to observe the eclipse himself…. When Myer learned where the 1878 eclipse would cross Colorado, he immediately focused on a prominent geographic feature that sat in the middle of the path. This was Pikes Peak, which rose more than fourteen thousand feet above sea level, dominated the horizon south of Denver, and held on its top a Signal Service meteorological post, the highest-altitude weather station on the planet. Manned year-round and connected to the outside world by a seventeen-mile telegraph line, the post imposed harsh duty on its small staff of resident soldiers, who endured electrical storms, hurricane-force winds, frostbite, and the nausea, headaches, and dizziness brought on by the thin atmosphere. Myer was intrigued. Having witnessed the 1869 eclipse from a mountaintop in Virginia, he was curious to know how this eclipse would appear from an even loftier height in Colorado. He hoped to go to Pikes Peak himself, but even if he could not, he wanted another qualified observer on the summit. After all, it was only appropriate for the nation’s meteorological bureau to take advantage of the eclipse to study the sun, since the sun drives the weather on earth.

On this rare occasion, General Myer and his chief scientist saw eye to eye. They agreed: Cleveland Abbe should go to Colorado. He should climb the mountain to observe the hidden sun.

And thus, the astronomer-cum-meteorologist joined the race to see totality, though the story of Abbe’s trek to the peak has a somewhat painful twist we won’t spoil for you. Baron’s book does a wonderful job weaving together these accounts of early American ingenuity as the scientists headed west, determined to prove their prowess during two minutes of darkness.

David Baron will be at the Smithsonian for a talk and book signing on June 6 as part of his book tour.

Read more of our 2017 eclipse coverage.