Drones Help to Map Historic Jamestown

Archeologists at Virginia’s 17th-century settlement have new ways to study old things.

:focal(1201x1532:1202x1533)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/ec/b7ecbd67-cc99-476b-8700-0e6dac21a81f/tw180115_078.jpg)

With the James River at their backs, archaeologists David Givens and Bob Chartrand launch a DJI Phantom 4 while standing in a small grassy area known as Smith’s Field on historic Jamestown Island in Virginia. The Phantom is a recent adoption by archaeologists, meant to help them discover details long since lost to history.

Captain John Smith, who in 1607 helped establish the first English settlement at Jamestown, drilled his troops in this field, thereby giving it its name. For years, Givens and his coworkers spent lunch playing touch football here. But rising ground water is turning the field into a swamp as the island sinks. Were it not for a 100-year-old sea wall, says Givens, the historic field “would probably be another stream” running into the James River. Givens is the Senior Staff Archaeologist at Preservation Virginia, the non-profit organization that acquired the Jamestown site in 1893.

He says rising waters are an underappreciated threat to history. Strong storms and high tides already flood the field with greater frequency than they used to, and a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration study predicted that the situation on the 1,500-acre island will only get worse due to climate change.

That prediction has enormous implications for future archaeological work. “It’s an overwhelming task. There are 26 sites identified on the entire island that are going into the water. So how do we deal with them? Which ones do we deal with? What time period?” asks Givens. “For 23 years we’ve been digging on an acre and a half,” referring to the original fort, which was thought to have been washed away by the James River until it was rediscovered in 1995. But the overall site also includes “a 40-60 acre town, not counting the other sites that are going under water. That’s why we’ve got to be agile with our tools,” says Givens of the drone-based mapping project that he and his colleagues are developing at Smith’s Field.

Working with 3-D survey software from Agisoft and Pix4D, Givens and his fellow archaeologists hope the drones will help them identify which sites need priority excavation.

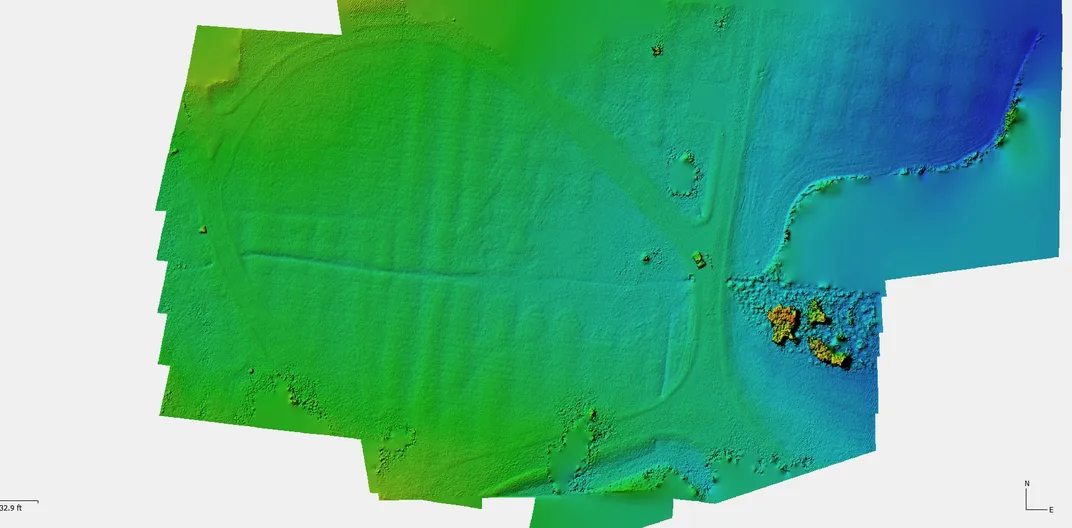

Overhead photography has long been a valued tool at Jamestown. In the past, archaeologists used ladders and even bucket trucks to capture images from above. LIDAR, a laser-based surveying technology usually flown on aircraft, is useful, but lacks the resolution that Givens and his group need. Traditional aerial photography is also insufficient. But drone-based imaging, where hundreds of digital photographs are blended together to reveal extraordinary detail, improves on those techniques by orders of magnitude. “We’re seeing incredibly detailed amounts of information,” says Givens. Whereas LIDAR could provide imagery at 30 pixels per meter, with drones “we’re seeing hundreds of thousands per meter.”

To illustrate, he leans over a laptop with a 3-D image of Smith’s Field created by the Phantom 4. Pointing to the screen, he says, “See that little track there? That’s where the Pepsi truck was turning around, and his tire made a little thing in the sand.” Asked to compare drone imagery with traditional aerial images, he says, “There is no comparison. You can’t get this kind of resolution commercially even if you paid for LIDAR.”

Givens stresses that the archaeologists are still very much in the starting phase of using drone imagery. “We’re not NASA. We’re not USGS. We’re just a couple of archaeologists that have a problem. We’re being confronted with a global problem here on our little slice of the world. In my mind, the story is that you can use very off-the-shelf technology” to combat a global problem.