America’s First Combat Pilots

Descendants of the volunteers who served in the famed Lafayette Escadrille shed light on why they chose to fight.

:focal(387x204:388x205)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/d4/82d47708-0c6b-442c-9367-0e880b57919e/lafayette_escadrille_group.jpg)

Former Air Force Chief of Staff General T. Michael “Buzz” Moseley calls them “the founding fathers of American combat aviation,” yet few Americans know their names. The 38 pilots of the Lafayette Escadrille, who flew for France beginning in 1916, before the United States entered World War I, created a culture that influences combat pilots today, Moseley says. They helped shape the U.S. Army Air Service when it was formed in 1918. “All the way up to the Army Air Forces and the U.S. Air Force,” says Moseley. “Having thought about this a lot and having lived inside that world for 40 years, I would say [Air Force culture] goes right back to those guys who decided in the spring of ’16 that this would be a good idea.”

Moseley is helping to lead a fundraising effort to restore the Lafayette Escadrille Memorial outside Paris. Built in 1928 with private donations, the monument commemorates not only the original 38 but the 200 or so who succeeded them as volunteers in various French squadrons, together known as the Lafayette Flying Corps. Forty-nine who died in the war are buried in the memorial crypt.

Today the monument is crumbling from water seeping in. Despite annual Memorial Day ceremonies jointly conducted at the site by the U.S. and French air forces, little has been done to renovate the structure. When Moseley was the Air Force legislative liaison in 2001, he managed to secure a $2 million appropriation for repairs. Since then, he has made the restoration of the memorial a priority. Last spring, the American Battle Monuments Commission, chaired by another former Air Force chief of staff, General Merrill “Tony” McPeak, signed an agreement with the French Ministry of Defense committing each side to raise $4 million to restore the memorial.

“The Escadrille reminds me a lot of fighter squadrons I’ve been in,” says McPeak, who flew thousands of fighter sorties and commanded a squadron of Misty forward air controllers, a hard-charging group who flew hazardous missions in Vietnam. “The cast of characters is quite colorful—the good and the bad, the skilled and the unskilled, the lucky and the unlucky. It was a very, very risky business. So it attracted some weird and colorful people, which is true even today.”

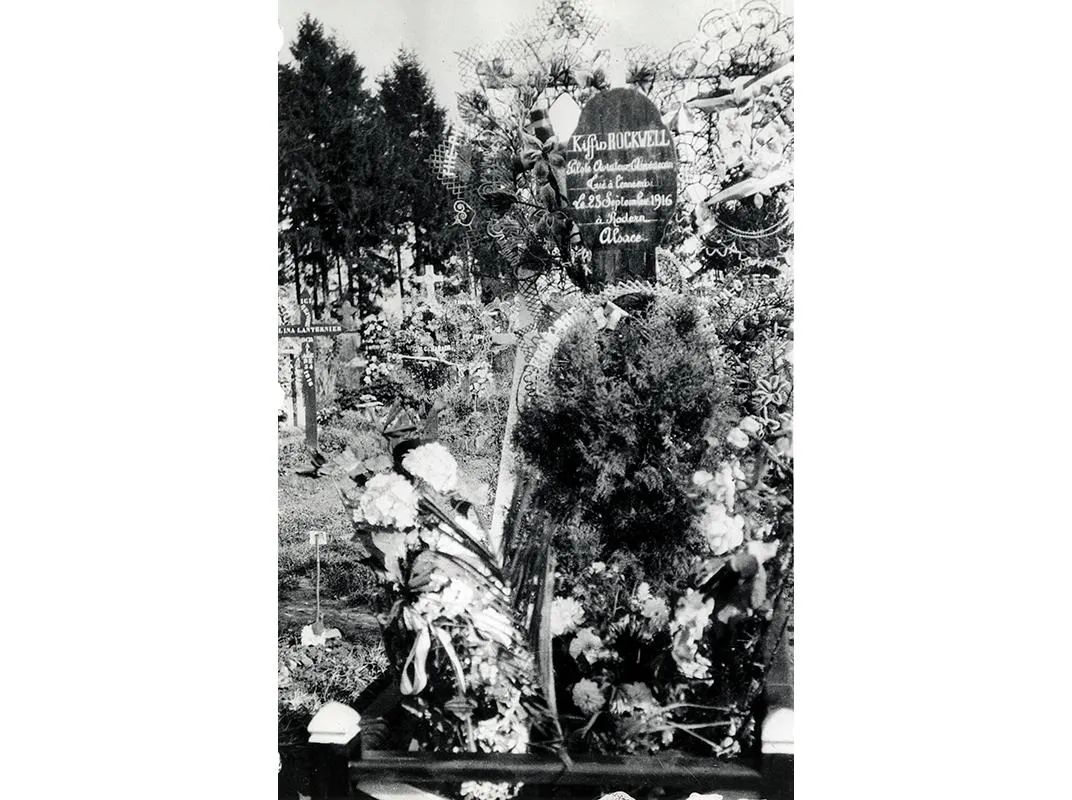

There was the paradoxical Victor Chapman, a New Yorker who was attending l’École des Beaux Arts in Paris when the war started. In letters home, he wrote lyrical descriptions of the French countryside, but in the air he was so aggressive that his rash attacks on German aircraft sometimes endangered his squadron mates. There was Raoul Lufbery, an adventurer and world traveler who, born in France of an American father, joined the French foreign legion in 1914. During his travels, Lufbery had worked as a mechanic on the airplane flown by French exhibition pilot Marc Pourpe, and the two became best friends. Pourpe joined the French air force, and when he died in a crash, Lufbery immediately signed on to train in French bombers. After flying Voisins with the Escadrille VB-106, he joined the American squadron to fly Nieuport fighters. “Raoul Lufbery flew, fought and died for revenge,” a fellow pilot once said. American journalist James Norman Hall got an assignment to cover the Escadrille for the Atlantic Monthly. Captivated by the personalities he met and by the romance of their cause, he joined the unit on the front in June 1917. (Hall and squadron mate Charles Nordhoff later co-authored The Mutiny on the Bounty.) And a pair of brothers, Paul and Kiffin Rockwell, were so devoted to military service and believed the French cause so “noble” that they enlisted on the day before the war’s opening battle, at Liège.

The two men credited with starting the unit were part of what was then America’s One Percent. From their privileged backgrounds came contacts that would eventually override objections to an all-American volunteer flying force fighting for France.

The Blue Bloods

William Thaw and Norman Prince “had the idea pretty much around the same time,” says World War I historian Blaine Pardoe. Thaw came from one of the 100 wealthiest families in the United States. (During her lifetime, Thaw’s grandmother donated $6 million to charity.) In 1913 he soloed in a Curtiss hydroaeroplane, bought for him by his dad. When the war began, he went to France hoping to join the French air service, but settled for the French foreign legion and fought in the trenches for months until the air service made him an observer. Despite bad eyesight, Thaw became an ace, and is probably the first American to fly in combat.

Prince may have been even richer than Thaw. When he was a child, he summered with his family at their estate in the French Pyrenees. He learned to fly at the Wright brothers’ school in Georgia and soloed in 1911. Frederick Henry Prince disapproved of his son’s aviation interests and forced the Harvard graduate into a law career in Chicago. The war gave young Prince a way out.

To form the Lafayette squadron, Thaw and Prince had to combat the resistance of U.S. isolationists as well as French military officers fearful of German spies. After unsuccessful individual efforts, the two joined forces and, aided by influential Americans in Paris and sympathetic French officials, managed to convince the French war department that an all-American squadron would generate U.S. sympathy and support for France against Germany. Squadron 124 of the French army air service was officially commissioned on April 16, 1916. It was known informally as the Escadrille Americaine, but after a German diplomatic protest that the national character of the unit violated U.S. neutrality, the French assigned it an official name: the Lafayette Escadrille, in honor of the French aristocrat who joined the Americans against the British in 1777.

The French Connection

Buzz Moseley points out that the militaries of France and the United States share a historical bond. “When I commanded theater forces for the first two and a half years of Afghanistan and Iraq—the first day, the French were with us in Afghanistan,” he says. He adds that the last time French and American soldiers were on opposite sides was during the French and Indian War, which ended in 1763. The French have kept number 124 an active squadron, and it still flies the Indian head insignia that decorated the aircraft of the original escadrille.

A French captain led the Americans of Squadron 124. Georges Thenault often flew on missions with his men “to keep an eye on my colts,” he wrote in his memoir, The Story of the Lafayette Escadrille. “The novices, Chapman, MacConnell [sic] and Rockwell, deliberately amused themselves by diving at the little smoke clouds,” formed by anti-aircraft guns. One of the stories Thenault includes in his book reveals his fondness for the Americans. The first of the airmen to be shot down was Clyde Balsley, who had left his home in Carbondale, Pennsylvania, first to volunteer for the American Ambulance Service. After his injury, “Balsley sent us a telephone message [from the hospital] that he would like some oranges, orange juice being the only nourishment allowed him,” Thenault recalled. “Immediately that good fellow Chapman offered to carry him some on his Nieuport. On the way, Chapman couldn’t resist the temptation of attacking the foe who had brought Balsley down.” Actually Chapman went up against five Fokkers—one of them possibly flown by the great ace and strategist Oswald Boelcke (see “Fighter Pilot’s Survival Guide,” June/July 2014). Chapman’s Nieuport was struck and came apart, and Chapman became the first to die. The unit was shaken. “We talked in lowered voices after that; we could read the pain in one another’s eyes,” wrote James McConnell, one of the original 38, in his biography Flying for France.

Today, Thenault’s grandson Georges III is a captain for American Airlines. Just this year he met a descendant of the man most instrumental in founding the squadron his grandfather commanded: Norman Prince’s great grandnephew, Regis de Ramel, also a pilot, who runs a flight operation outside Philadelphia. The two talked about their famous forebears. Thenault commented on the continuity between his grandfather’s flight training and his own. “He went to [the military academy at] Saint-Cyr, and was in the Chasseur Alpin [elite Alpine regiment]. His career progression sounds so much like a pilot today: You go to school [at Pau], you graduate, they keep you on as a flight instructor, and then you move on to something else.” De Ramel tried to imagine what it must have been like to command the singular squadron his great uncle helped found. “Captain Thenault must have been someone who could keep herding the cats in the same direction so they wouldn’t kill each other,” de Ramel told Georges III. “He had a bunch of alphas who started it,” he said.

Why Norman Prince went to war has been a subject of discussion between Regis de Ramel and his twin brother Guillaume, who grew up hearing stories about the family patriarchs. Regis points out that it took courage for their great uncle to counter his domineering father, Frederick Henry Prince, who “was pretty intent on having everyone do exactly what he wanted them to,” says Regis. Guillaume, a private pilot, believes there was something more to it than the desire to escape. “He could have been doing air races and America’s Cups, but he abandoned all that to go to France,” says Guillaume. “I don’t think it was just because he was looking for adventure. I think he really did love France.”

A Couple of Rascals

For air-minded Americans who won’t be able to travel to Paris in 2016 for the Lafayette Escadrille centennial, there is the Vintage Aero Flying Museum in Lupton, Colorado. President and director Andy Parks inherited one of the world’s largest private collections of World War I aviation uniforms, medals, and other artifacts, which he maintains and displays, he says, to honor the memory of the pilots he met as a young man. Because his father, the son of a World War I artillery soldier and aviation enthusiast, helped organize several reunions of the Lafayette Flying Corps, the pilots gave him many of the mementoes now assembled in the museum. (Jim and Andy Parks were made honorary members of the Corps at its last reunion in 1983.)

Among the treasures at the Vintage Aero Flying Museum: a 1915 uniform worn by original squadron member Elliot Cowdin. Cowdin humanizes the squadron, according to Parks, because unlike the others, he didn’t try to be an idealistic knight of the air. “He’s kind of a rascal,” says Parks. “He was a good poker player and the guys lost a lot of money to him, and some of them started to despise him.” Cowdin left the unit early. “But you have to give [him] credit because he was the first American ever to receive the Médaille Militaire,” says Parks. “He fought against Boelcke and [Max] Immelmann and the very best of his era.”

Another rascal in the squadron left because he was asked to. Bert Hall was an ex-taxi driver of questionable ethics who eventually served time in U.S. federal prison. “Bert lied about every aspect of his life,” says Blaine Pardoe, author of the biography The Bad Boy: Bert Hall, Aviator and Mercenary of the Skies. First, he lied about being a pilot. “He showed up at [the training field in] Pau and said, ‘I’m an aviator,’ and they said, ‘Show us what you can do,’ and he climbs in this airplane and crashes it into a barn.” Still, the French instructors were impressed by his courage. Throughout his brief service, he maintained a reputation for fearlessness and, in the end, was one victory short of becoming an ace. “Hall makes this American,” says Pardoe. “It’s not just an elite group of men who can go fly.”

Nor did the antics of Cowdin and Bert Hall tarnish the reputation of the Escadrille in the States. The U.S. press trumpeted tales of their exploits, regardless of whether they were true. Lufbery was particularly guilty of exaggeration. “[The stories about his past] were colorized by propaganda, or by the fact that Lufbery told tall tales, partly because he found it amusing, and partly because he didn’t understand the power of the press,” says biographer Bill Jackson. The dashing image created by the press was enhanced when Thaw, on leave in Paris, acquired the first of two lion cubs, which became the squadron mascots. The first he named Whiskey; the second, Soda.

In the Parks collection, a letter to James Norman Hall hints at the fame the pilots enjoyed back home. Hall, one of the rare survivors, was nearly one of the fatalities. On one mission, he mistook a squad of German fighters for his own unit. When they fired, he felt “a smashing blow in my left shoulder accompanied by a peculiar sensation as though it had been thrust through by a white hot iron.” He passed out as his airplane began to spin. He regained enough consciousness to pull out of the spin with 500 feet to spare. With no idea where he was, he passed out again. When he woke up, he was on a French stretcher, with no memory of how he landed. After recovering, he returned to his unit. No wonder the pilots became heroes to those who read about them.

Hall’s daughter donated the letter to her father to the Vintage Aero Flying Museum. “It’s from a librarian who wrote to him in 1917, basically saying how much she admired him for going to fight for the French,” says Parks. She wrote: “It is with genuine thanksgiving that I read in this morning’s paper that you were out of danger. Perhaps I am very bold in writing to you but I only hope that what I am going to say will bring you a bit of well-earned gratification.”

The squadron was fulfilling the purpose of its founders. According to Douglas Lantry of the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, “The publicity it garnered and the political and cultural effects of its fame were more important than its number of aerial victories.” Hundreds started to volunteer.

From Romance to Reality

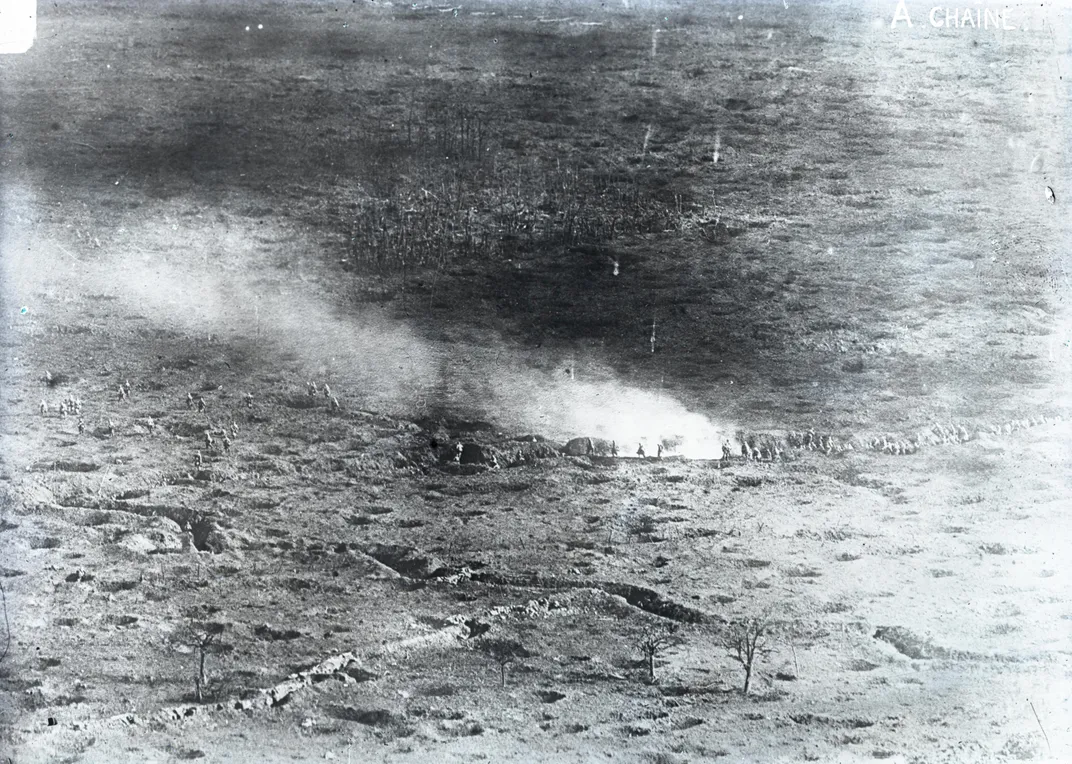

From the fall of 1916 through February 1918 (the month the Lafayette pilots became part of the U.S. Air Service), the unit was sent to 11 positions along the Western Front and flew over some of the most horrific battlefields in the history of war, including Verdun and the Somme. They graduated from the tiny but agile Nieuport 11 to the more powerful Nieuports 17 and 28, and finally the SPAD VII and XIII. Their mission was to shoot down German fighters. “The air war there was clearing the skies for the observation planes to get their photos in so the guns could be aimed to hit their targets. That’s what they were doing on a day-to-day basis,” says Bill Jackson.

“It’s hard for us to imagine today how dangerous this work was,” says McPeak. Of the 38 pilots, nine were killed in combat; at least six more were shot down or injured. Norman Prince died after the unit’s first mission as bomber escorts. While landing in the dark, he crashed into a telegraph line.

Lufbery, the unit’s first ace, also scored more victories than any of the others. Part of the reason for his skill was physical—he had excellent eyesight, and was a crack shot. But his experience as an airplane mechanic may have been his greatest advantage. “Your biggest enemy as a World War I pilot was your own plane,” Jackson says. “He systematically reduced a lot of that risk. He drank with the guys, he partied when he went to Paris, but when he was on the airfield, he was most likely in the air, resting up, or in the hangar with the mechanics.”

Lufbery’s grand nephew, Raoul Lufbery III, is retired and living in International Falls, Minnesota, after a long career with the National Park Service. He never met his great uncle, but he heard stories from his grandfather Charlie Lufbery, who had enlisted with his famous brother in 1914. His uncle, he says, was famous for the care he gave to his machine. “Anyone would take a used Lufbery plane before they’d take a brand-new plane,” he says. Knowing that the Lewis guns frequently jammed, Lufbery also lavished attention on the gun. “He polished every round before they went in the drum,” says his grand nephew.

Their Legacy

On January 1, 1918, the U.S. Army Air Service was established, though it took several months to arrange the transfer of the Lafayette pilots. “I left it with deep regrets,” wrote Georges Thenault of the disbanded squadron. He called them “an eager, fearless, genial band…each so loyal, all so resolute.”

James Norman Hall became a captain and was eventually awarded the Distinguished Service Cross as well as the French Croix de Guerre with five palms. William Thaw went on to command the 103rd Pursuit Squadron in the Air Service and was awarded similar honors. Triple ace Raoul Lufbery became commander of the 94th Aero Squadron, the famous Hat in the Ring gang that made Eddie Rickenbacker famous.

When they entered the U.S. Army Air Service, the Escadrille pilots had, in some cases, nearly three years’ combat experience; the new Army pilots had none. The experience of the Escadrille helped their newer squadron mates meet the test of aerial warfare. Lufbery led Eddie Rickenbacker on his first sortie. “When they came back,” says Bill Jackson, “He asked Rickenbacker if he’d seen any Germans, and Rickenbacker said no. So Lufbery told him to look at his plane and there were four holes in it.” On May 19, 1918, Lufbery fell to his death from a burning SPAD.

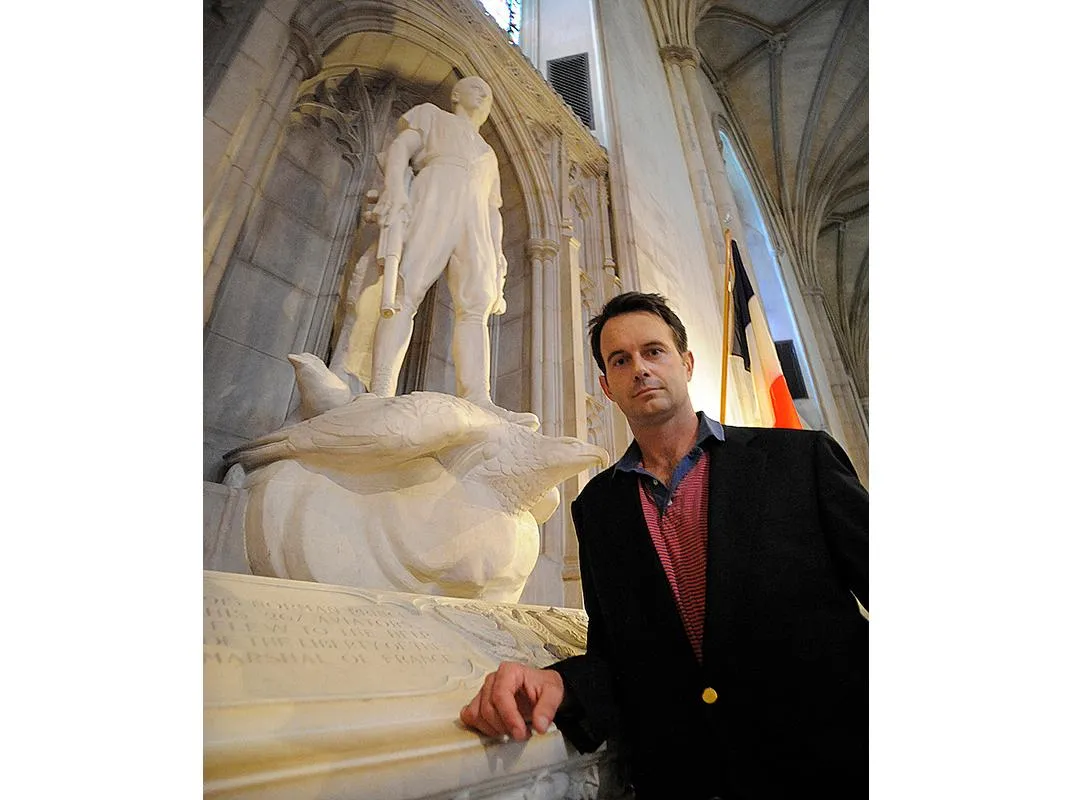

The culture that former Air Force Chief of Staff Michael Moseley alludes to—an esprit de corps and a shared dedication to a cause—was, in one case, handed down directly from fathers to sons. Major Nick Rutgers is an F-15C pilot for the Oregon Air National Guard. Previously he flew the F-15 with the U.S. Air Force. His father was an airline pilot, who flew Cessna O-1 Bird Dogs in Vietnam and helicopters for the National Guard in Hawaii. His grandfather flew as a radio operator/gunner in TBM Avengers in World War II. And his great grandfather was James Norman Hall, one of the original 38 members of the Escadrille.

Rutgers says he has a hard time imagining what it was like to fly as a member of the Lafayette Escadrille. “What they did…was so personal, so close—so vivid for them. What we do is at such a longer range and with way more capable aircraft,” he says.

What he says about his own military career points out more continuity than contrast with those pilots who flew 100 years ago and reveals another motive of the Lafayette volunteers. “I cannot remember wanting to do anything else in my life,” says Rutgers. “As long as I can remember, I’ve always intended to be a pilot, perhaps even a military aviator. I always knew what I wanted to do, and it gave me a goal.”

He says he’d like now to learn to fly as his great grandfather did—in an open-cockpit taildragger. He may have the chance. His grandmother, Nancy Hall Rutgers, James Norman Hall’s daughter, recently funded the construction of a replica SPAD, which is now in the collection of the Vintage Aero Flying Museum. It will almost certainly be flying on April 16, 2016. Perhaps Rutgers will be in the cockpit.