America’s Next Spaceship

Designed to go where no man has gone before.

:focal(1599x2316:1600x2317)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9d/60/9d60ddec-17c0-4be8-98cd-2b7099e1bb78/13t_am14_orionmpcvart_live.jpg)

“This is all the space for you and your three closest friends,” says Brad Holcomb, a project manager at Lockheed Martin’s Exploration Development Laboratory in Houston, as I settle into the commander’s seat on the low-fidelity mockup of the Orion capsule. Having clambered my six-foot-three-inch frame down through the hatch opening (an isosceles trapezoid, with black-and-yellow caution tape along the top so visitors don’t smack their heads), grabbed a handy yellow strap as I reclined, and swung my legs into a flexed, upright position, I couldn’t imagine working, or driving anything. However normal this position may seem in space, here it felt unsettling.Holcomb is in the same position in a seat a few feet away. Speaking with him—the first interview I have ever conducted on my back—I cannot shake the feeling you get when you climb into a new car with a salesman: resting your hands on the wheel, puzzling out the unfamiliar dashboard, shifting your lumbar region against leather. In this case, however, the seats are severely unaccommodating machined aluminum (the operational version will be upholstered); the windows, shaped roughly like a pair of Aviator shades turned upside down, are above my head; and do not go looking for any cup-holders—though there are other nifty features, like space-saving foldaway seats. While not what you would call expansive, Orion is roomier than the three-astronaut Apollo command modules were. Like a third row seat added to a minivan, the extra 135 cubic feet of habitable volume in Orion is enough to carry a fourth astronaut. In this “mid-fidelity” mockup, the interior is white and spare, and rather than a complicated instrument panel with a hundred switches poking out of it, the cockpit will feature three touchscreens, placed at eye level.

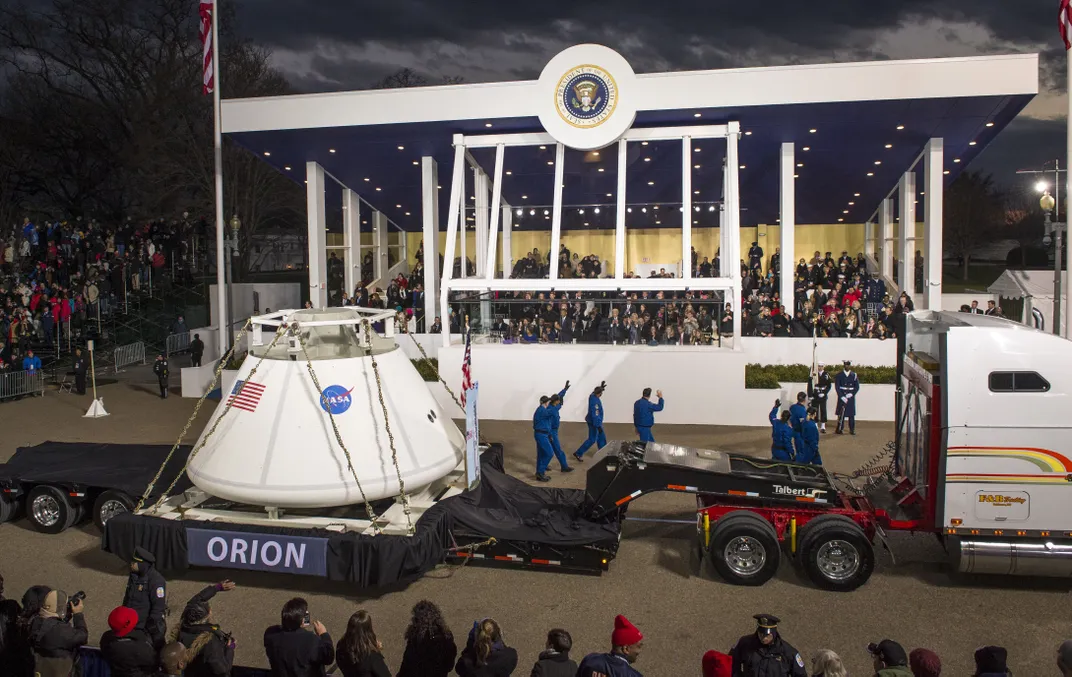

Orion spent years in a high-flying theoretical orbit, and has so far survived the punishing turbulence of reentry into fiscal realities and shifting political desires. In 2006, NASA awarded Lockheed Martin Space Systems $6.1 billion to build spacecraft for the far-ranging Constellation program of human exploration. After the program’s cancellation, Lockheed Martin began work on a contract, extended to 2020, to build spacecraft for three missions. The first flightworthy capsule is being readied (in June, technicians at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center mated the crew and service modules) for its uncrewed 3,600-mile ride this December, after its launch atop a Delta IV Heavy rocket. Orion is the heart of NASA’s most ambitious crewed vehicle ever, a vessel that will carry the human space program for the next 30 years and could see everything from lunar exploration to a variety of still-unfolding asteroid recovery missions to, eventually, it is hoped, a mission to Mars.

Not that astronauts would be expected to log that flight in the Orion command module; for a Mars voyage, a larger habitation module would be attached. There is even talk of having habitation modules stocked with supplies and waiting in space at crucial junctures, like highway rest stops.

Car metaphors may be trite, but while I walk around Lockheed’s laboratory, in a sprawling office park not far from the Johnson Space Center, they keep coming up. (And after all, Lockheed designers did get advice on the capsule’s seat-restraint systems from seat designers for NASCAR.) To explain the difference between a spacecraft designed for a Mars mission and one for low Earth orbit, for example, Linda Singleton, Lockheed’s Orion program integration manager, reaches for the RV comparison: “If you have a car and an RV, you’re not going to run to the grocery store in your RV to get milk,” she says. By contrast, sleeping in the “car” might be acceptable for a one-week jaunt to the moon, but for a nine-month Martian road trip you will want some of the creature comforts of a Winnebago (i.e., a habitation module). Of the spacecraft being developed by companies NASA has hired to ferry people and things to the International Space Station, she says “we kind of call them taxis.” As opposed to the 20,000-mph, 4,000-degree, 12-G reentry that Orion will eventually experience from a deep space jaunt, “the low Earth orbit is a Sunday drive,” Holcomb notes. As we walk around the capsule exterior, I point out to the Lockheed team that, as with the anthropomorphic headlights and grills of most car designs, the front of Orion has a “face.” Purely unintentional, they tell me. Squint a bit and you almost see a less-threatening version of a stormtrooper helmet from Star Wars.

The last time humans left Earth orbit, cars ran on leaded gas, few models had power steering, in-car entertainment was an AM radio, cruise control was a novelty, and air bags were unheard of. So how has something as representative of the Space Age as a space capsule changed in that time? As NASA prepares to launch a vehicle that someday, according to the agency’s “road map,” will go farther into space than any before it, I wanted to look under the hood of this new-model capsule and understand how the agency has designed for distance.

***

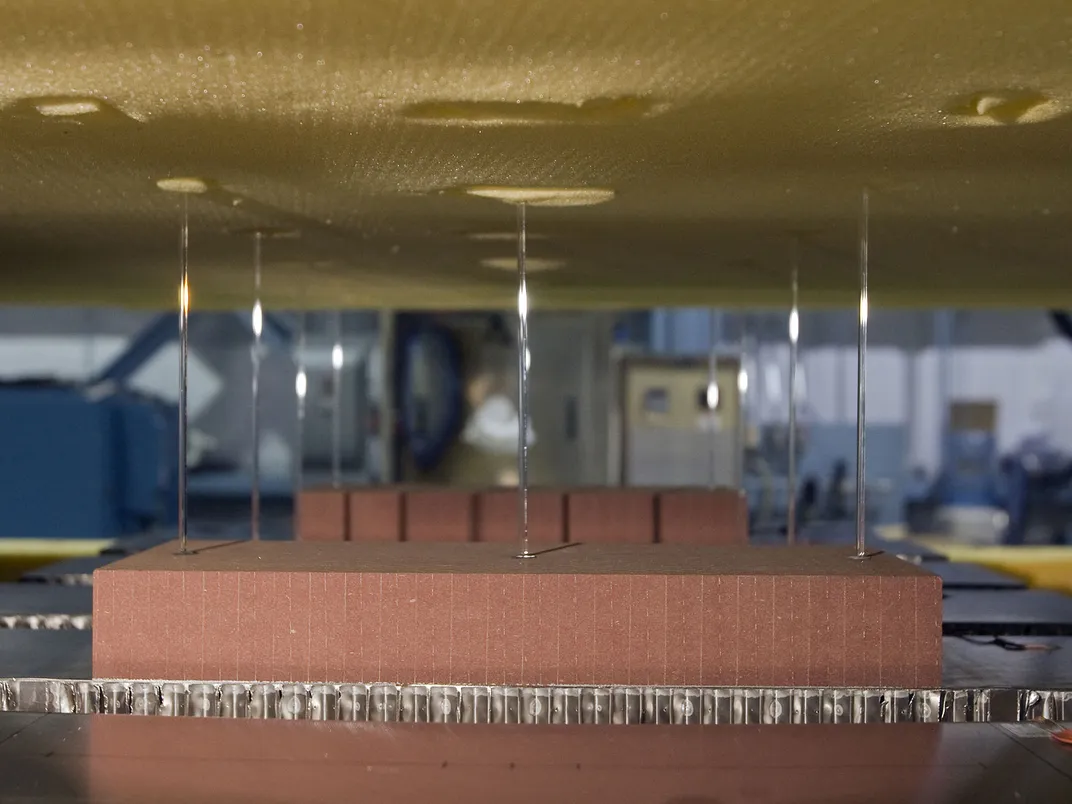

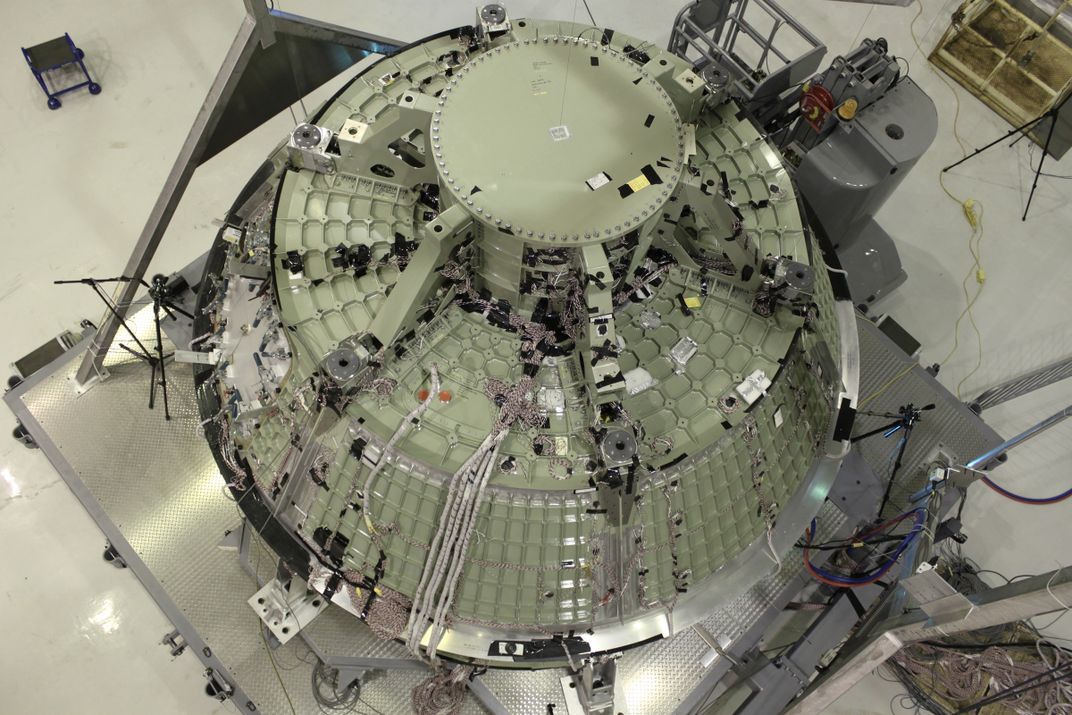

If you were around for Apollo, you’ll recognize Orion. Its conical form comes deep out of Apollo aerodynamic studies and tapers from its base to its lopped-off apex with a barely perceptible 2.5-degree change in the angle that defined the Apollo capsules. When Cleon Lacefield, Lockheed vice president and Orion’s program manager (a former NASA flight director in the space shuttle program), tells me Orion is using the same Avcoat-clad heat shield as Apollo (besting some eight rival materials), I ask how much the 1960s material has evolved. “Not much!” he says, adding that the heat shield is a testament to the engineering ingenuity of the Apollo program. In addition, he notes, since Orion designers were trying to take so many things to the next level, “where we didn’t have to take something to the next level, we tried not to.” Still, Lacefield points out, a “lot of work” was done to improve Avcoat’s thermal properties and strength so that it will withstand the higher reentry loads Orion will experience.

Like the honeycombed Avcoat surface, the resemblance between Apollo and Orion is skin deep. Josh Hopkins is a Lockheed Martin engineer who leads a team designing the concepts for missions that Orion will some day fly. He says that while some may have wanted a next-generation crewed spacecraft to look more next-generation, another mindset is “Hey, the Apollo design worked, and physics hasn’t changed in that time, so let’s start with that approach.”

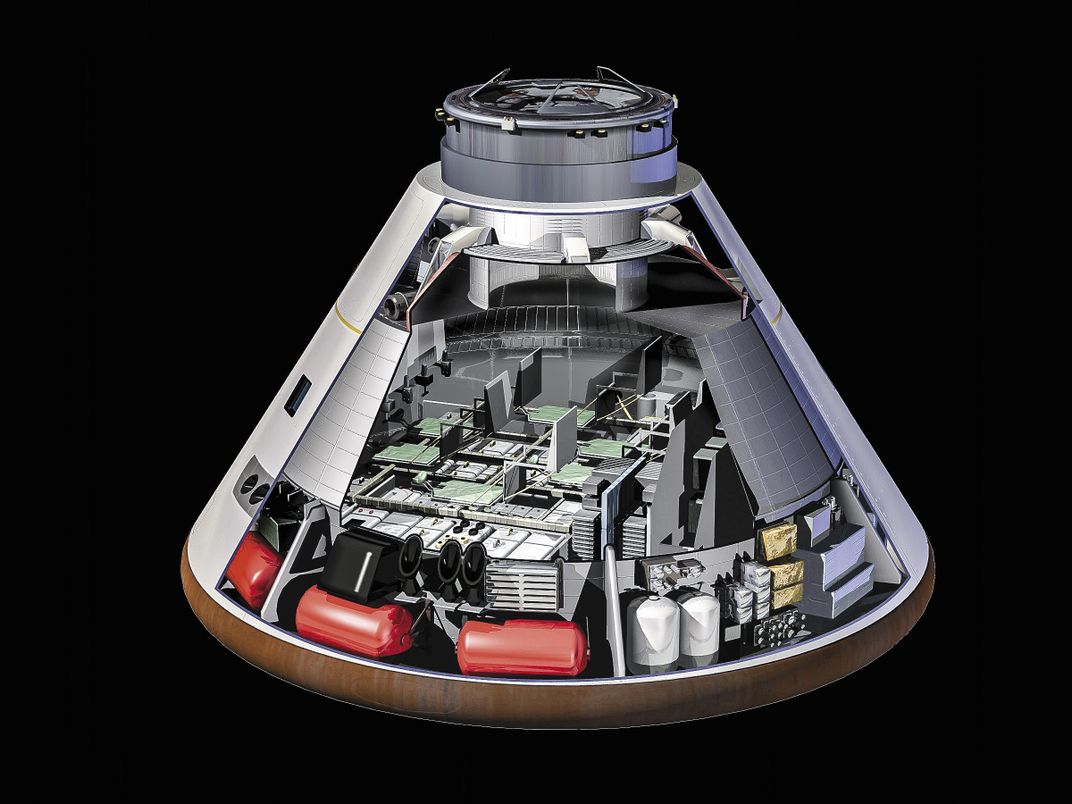

There are obvious differences: Orion is 30 percent larger in diameter to accommodate longer missions. Internally, says Hopkins, “you have twice the volume. There’s room to put things like a toilet. On Apollo, they had plastic bags. On a two-week trip that could be tiresome.”

Just as the most dramatic changes made in automobiles since the 1960s have been in passenger safety, one of the most significant areas of design evolution in Orion is crew safety. Much of the increased hardness (and weight) of the capsule, says Lacefield, is due to the requirement to make the craft able to withstand a launch failure. Orion, in the event of catastrophe on the launch pad, is rocketed away from its launcher and can be lifted “a mile up and a mile over,” says Lacefield, before it descends under a parachute. That abort system comes with a weight penalty—some 16,000 pounds, more than half the weight of the 22,000-pound crew capsule itself. The burden of weight—“Every pound you add in the weight means several pounds of fuel to get it up,” Lacefield says—is the reason designers scrapped the early idea of a terrestrial landing system, which would have required more cushioning to keep from crushing the humans inside—about 1,400 pounds more—than a water landing system. And yet because of Orion’s deeper journey, and its potentially rougher return ride, bulk had to be added nonetheless. On the space shuttle, Hopkins says, the “decision to deorbit would be made about an hour before landing, so they could essentially check the weather at the landing site.” But on a lunar mission, “you make a commitment to come home about four days before you actually land.” With cooperative weather a probability at best, “you have to be able to tolerate a wider range of weather conditions on landing.” Higher wave heights, for example, can make the landing more troublesome. “When the spacecraft comes down and touches the water, what it really wants to do is come in at an angle,” Hopkins says. “It doesn’t want to belly flop.” But higher waves make it harder for the capsule to make that slicing racing dive; imagine waterskiing across the wake of the boat’s waves versus calm water. Although engineers removed, through various iterations of the design, upward of 1,000 pounds from the Orion heat shield, the one place where structure was added was the part of the capsule that would land in the ocean “feet first” (the astronauts’ feet, that is).

On a deeper, longer mission, there are more chances for things to go wrong, more exposure to radiation and micrometeorites. Says Hopkins, “People on the ground, or astronauts on the space station, are protected from solar storms or galactic cosmic rays to some extent by the strength of the Earth’s magnetic field.” If a spacecraft is to push beyond that field, it will need more protection. This entails everything from better data (from high-powered computing) on where cosmic rays are penetrating a spacecraft to better sensors monitoring the radiation environment. “If it gets bad,” Hopkins says, “the astronauts can move some of the cargo around inside the spacecraft to create a ‘storm shelter’ in the spacecraft, a little bit like kids building a fort out of couch cushions.” Water, stored food, spacesuits—almost any supplies could be used. They help eliminate the need for (and the weight of) material with the single purpose of shielding the ship from radiation. (The service module structure is a radiation buffer on the ship’s blunt end.)

It’s not just astronauts that need shielding: Modern avionics, says Hopkins, have smaller circuits and are thus more vulnerable to radiation. “In modern electronics, as everything has gotten smaller and everything is closer together, there’s a smaller amount of electric current required to flip the switches in the circuit. It used to be that getting hit with a stray particle of radiation wouldn’t have had enough energy to damage big wires and vacuum tubes,” he says. “As things get smaller, it’s easier to flip a bit from a zero to a one or to damage the electrical circuitry. That’s one reason that spacecraft might not use the latest and greatest computer chips like your iPad might use.” So shielding and redundancy have been added.

Going long, the astronauts will depend on the Deep Space Network for communication and must be more self-reliant; there are fewer chances for help. “On [the space station] or shuttle,” says Hopkins, “if something goes wrong [like a sick astronaut], you have the option to come home pretty quickly.” So the Orion design includes many levels of redundancies and “down modes,” says Lockheed’s Lacefield. “We could lose [Orion’s main engine] on the other side of the moon,” he says, holding a model of the Orion and its Space Launch System rocket, “have a problem with our primary avionics, and have a hole in the cabin and still get the crew back.” Things learned with Apollo are reflected here: For example, because of the fire hazard of an all-oxygen cabin, the astronauts will breathe a mixture of gases, even in flight. The carbon dioxide “scrubbers,” whose pending failure was famously depicted in the film Apollo 13, have been replaced, Hopkins says, with a new system that can absorb carbon dioxide and release it later. When the reusable absorber becomes saturated, the astronauts will open a vent and the CO2 will be released overboard. This technology for keeping the air breathable has no time limit, and without it, humans would be restricted to short stays in space.

When the space shuttle was being designed, its creators believed that it would always operate as a pressurized vessel. Only after the Challenger disaster were the astronauts given full-pressure suits to wear during launch and reentry, and although switches and controls had been designed for spacegloved hands to manipulate, the astronauts had difficulty with them when their suits were pressurized. During the Columbia accident investigation, NASA determined that three astronauts weren’t wearing their gloves and one was not wearing a helmet.

Orion is being designed from the start to be operated, if the need arises, as a depressurized cabin. The requirement for the astronauts to operate while wearing pressure suits influences everything in the design of the cabin, from the size of the hatch to the location of the seats (they need to be pushed a bit farther apart). Extensive suit studies were played out in the mockup “so we could understand reachability,” says Holcomb. “Are things easy to see? Can you adjust the lighting? What are you running into, what are you catching on?”

***

A key moment in sci-fi film history, described by designers Nathan Shedroff and Christopher Noessel in their book Make It So: Interaction Design Lessons from Science Fiction, may have had an influence on the look of future spacecraft (and consumer electronics). It happened in the late 1980s “[w]hen Star Trek replaced controls based on mechanical, lighted buttons in the original TV series with the backlit touch panels in its first sequel series, Star Trek: The Next Generation.” The authors report that the production designer, rather than being visionary, simply did not have the money to create individually installed, lighted buttons, so instead he simply used backlit plastic film with controls printed on them—which, curiously enough, turned out to be prophetic of today’s touchscreen technology.

We had come to associate space travel, at least in science fiction, with complex operating environments: astronauts surrounded by banks of switches and indicator lights. In the 1979 Alien, a visit to “Mother,” the operating system of the Nostromo, entails sitting in a capsule-like room, entirely enveloped in a vast array of twinkling lights that do not seem to convey actual information—other than that the computer is (presumably) thinking.

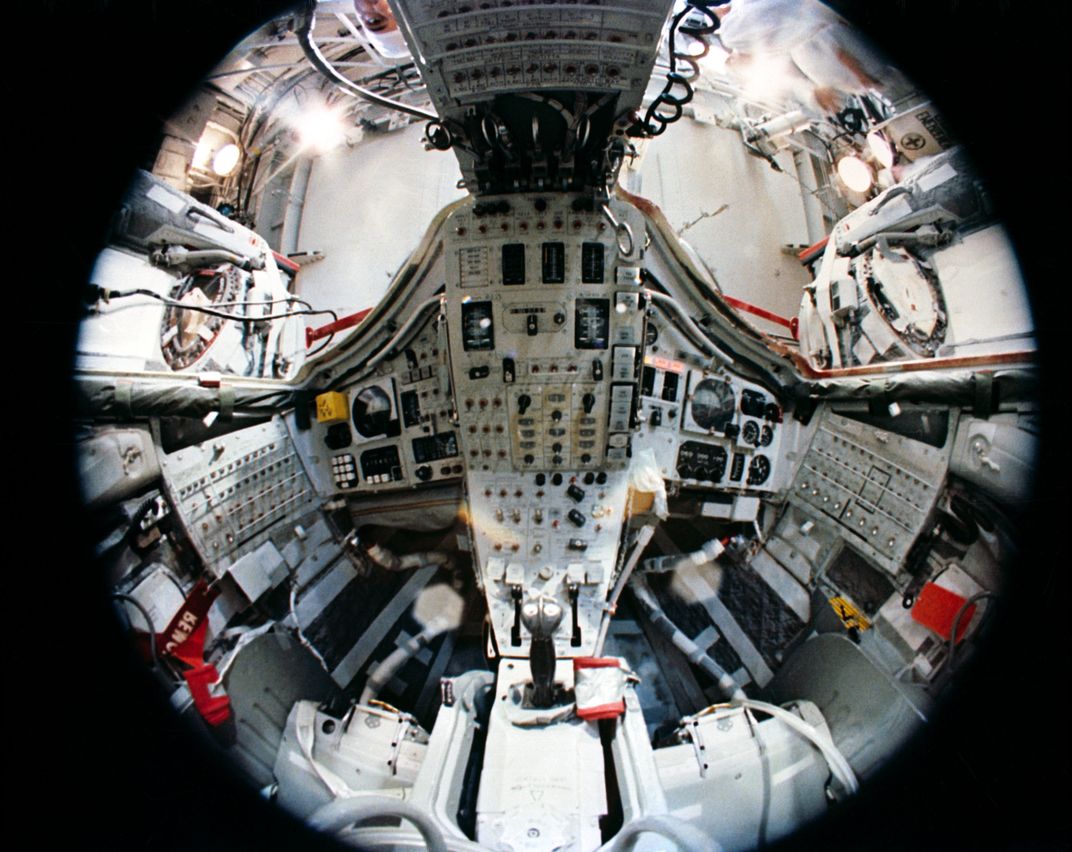

In real-live spaceflight, the environments have hardly been less complex. NASA astronaut and space shuttle veteran Lee Morin, wearing a blue jumpsuit with a “Mach 25” badge, tells me that the shuttle cockpit had 1,249 switches. “There were approximately 2,000 for the whole vehicle,” he says.

On Orion, almost all of those switches will have disappeared, or, as Morin says, will have “gone onto the glass,” the glass being one of the three flat-panel displays (ringed by, yes, switches) mounted at the astronauts’ eye level. Morin has been working on such displays since 2005. “Apollo was a brilliant cockpit,” he says, “but everything there basically had one use—a physical gauge, a meter. We were not going to be able to do much with that approach.”

Rather than replicating instruments in graphic form on a screen, Orion will have a sophisticated system, dubbed “eProc” (for electronic procedures), that will automatically bring up the relevant display page for the procedure the crew is working on. There will be switches for “a few emergency things,” he says, but without the banks of controls, the cabin will be much visually cleaner (and lighter). Three screens, but four astronauts? The “result of a long optimization process,” he says, balancing weight, power, and the crew’s ability to reach controls. “When we went from four to three screens,” he says, “we canted these outboard ones down 10 to 12 degrees to facilitate cross cockpit viewing.” Orion could also have a crew of only a commander and a pilot. A joystick helps during moments in flight when reaching the screen would be difficult.

The old paper flight manuals (all 250 pounds of them) will be jettisoned. While Morin concedes that switches and analog manuals have their virtues—blindfold a pilot and he can still locate a cockpit switch by muscle memory—he says the new system can reduce workload and improve coordination. “When I flew, I had four checklists velcroed to my thighs, just for nominal entry,” he says. “Now picture the off-nominal scenario: All of a sudden you have to do it in a different way because you don’t have enough fuel, or you have to do the deorbit burn on one engine. You have to do that in the next 30 seconds or you’re in real trouble. You have to get everyone on the same page. I have to flip switches at the same time with that guy. So it’s all bang, bang, bang. Here there’s less of that coordination between people and coordination between books.” What is key for Orion, says Morin, is bringing down the “training footprint.” Unlike the shuttle, with its trained pilots, “flying Orion is just a little part of your job. You might operate Orion, go somewhere to a habitation module or [to a halo orbit in deep space]—three months later, now it’s time to get back in here and fly.” While Orion’s reentry will be more automated than the shuttle’s, Morin says there are still critical tasks that “astronauts wouldn’t have been training on two weeks earlier.” The goal is to make it easier. Says Morin, the “less quirky stuff you have to remember not to do,” the better.

While it is not hard to see the influence of wider consumer technology in the new screen-led environment, it is not a simple matter of installing consumer-grade equipment. As I find myself on my back for the second time—this time in NASA’s mid-fidelity Orion mockup—John McCullough, Orion’s Vehicle Integration Manager, tells me that the capsule’s potentially depressurized status changes the equation. “If that hatch is open, all your electronics have to be able to function in zero pressure and no air. You can’t air-cool your electronics,” he says. Space is cold, but electronics produce heat; you can hear your computer’s fan running to cool it off. But fans don’t work in a vacuum; instead, the engineers will use cold plates that circulate liquids in a loop for cooling. This is not a new problem, McCullough says. Apollo electronics had to operate under the same conditions. Orion is designed to withstand multiple depressurization-repressurization cycles.

***

The famous designer Charles Eames once said, “Design depends largely on constraints.” Perhaps nowhere is that more true than in the unforgiving, exacting, bizarre environs of space, where missions are defined by the limits of technology, amounts of life-giving “consumables,” and human physiognomic capacity. Spacecraft design starts conservative, and designers progress by seeing what can be taken away: Less (weight) is more (mission). “In the last design cycle we’ve taken out over 4,000 pounds,” says McCullough. Some of this involves rethinking entire systems, like the strut-supported crew seats required for terrestrial landing; some of it comes from working creatively with what you have, like using the mass of the crew to function as ballast, or using clothing as a packing material. But the whole process is integrated. On one end, improvements in the astronaut’s gloves enabled more buttons to be placed around the command screens. On the other, McCullough notes, the Space Launch System rocket is being built at the same time. The requirements interact, mesh or clash, and change.

The crew is part of that process, and the design is driven by questions about them, says McCullough. “If you lose a crew member, are you able to take care of one another? If I lose contact with this vehicle, the crew has to pilot themselves back. Those are the things you don’t have to worry about in low Earth orbit.” As we rest on our backs, gazing into the screens that may one day display Martian landing procedures, McCullough says, “It’s a part of growing up, humanity growing up and stretching out. To be able to say ‘I’m not tethered to the Earth anymore.’ ” Orion is being designed to break the tether.