Inventing the Invisible Airplane

When camouflage was fine art.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/17/a0/17a06d4a-16f8-45f2-8e64-6f9407dab524/03k_jj2016_gavinconroy-the-vintage-aviatorconstrutorsofmilitaryaircraft_live-wr2.jpg)

In her 1917 patent application, Mary “Mitty” Taylor Brush claimed that with her invention she was “able to produce a machine which is practically invisible when in the air.” Mitty and her husband, renowned artist George de Forest Brush, believed they could use ideas developed in paintings to create camouflage for aircraft. George first developed a skill for these techniques from his friend Abbott Thayer, a painter who had tried to get the U.S. Navy to adopt his ideas for concealing ships during the Spanish-American War. In 1916, when it appeared imminent the United States would enter the war, George bought a Morane-Borel monoplane to experiment with, and soon his pioneering wife, trained as a pilot, applied her genius and flying skills to further his work. Call it the art of war.

“Early in World War I, it was the French army that established history’s first dedicated camouflage unit,” says Roy R. Behrens, a professor of graphic design at the University of Northern Iowa who has written several books on the history of camouflage. “That unit comprised soldiers who in their civilian lives had worked in art-related professions, such as painting, illustration, graphic design, architecture, theatrical set design, and so on.” Other countries followed suit, with the United States creating the 40th Regiment of the Corps of Engineers (Camouflage) in 1917—though only after a private society of civilian artists, including Lincoln Memorial architect Daniel Chester French, published an article insisting the War Department accept their services. In addition to shrouding gun emplacements and concealing battleships, the men of the regiment began to apply their artistic styles to making aircraft more difficult to spot. The result: World War I aircraft sporting some unusual livery.

Seen up close, the wings of an Albatross D.Va appear garish, covered in a pattern of large, multicolored, misshapen dots called lozenges. This camouflage was inspired by pointillism, an Impressionist technique in which neighboring bits of color appear to blend with one another as the viewer moves away from the image. The effect would make a patrolling Albatross recede into the surrounding sky, says Behrens.

In 1916, when a German infantryman named Paul Klee turned out to be a highly skilled artist, his sergeant shipped him off to Oberschleissheim air field, near Munich, to paint repaired aircraft. Klee and his crew traveled around the region by train to collect crashed and otherwise broken aircraft and paint lozenge patterns on them. Many of these aircraft looked like Klee’s fine art pieces. Writing in his diary during the war about his personal work, which he continued to produce, he seemed affected by the camouflage nature of his creations: “Everything vanishes around me, and works are born as if out of the void. Ripe, graphic fruits fall off.”

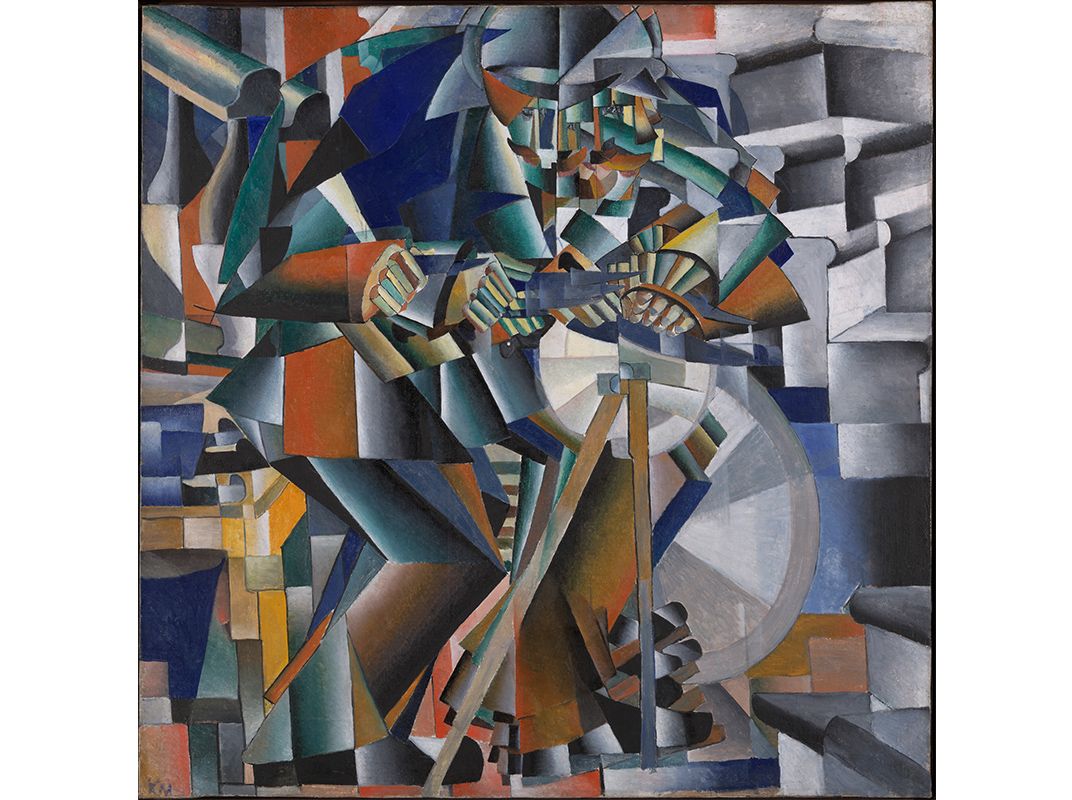

On the Allied side of Europe, British illustrator Norman Wilkinson developed a scheme he called dazzle camouflage for ships, which was quickly adopted for ground vehicles and aircraft. Pablo Picasso is said to have recognized the style immediately, according to the biography Gertrude Stein wrote about her friend. She describes a day when the two stood together in Paris at the beginning of the war. As camouflaged trucks drove by on their way to the front, he cried, “Yes, it is we who made it, that is Cubism!”

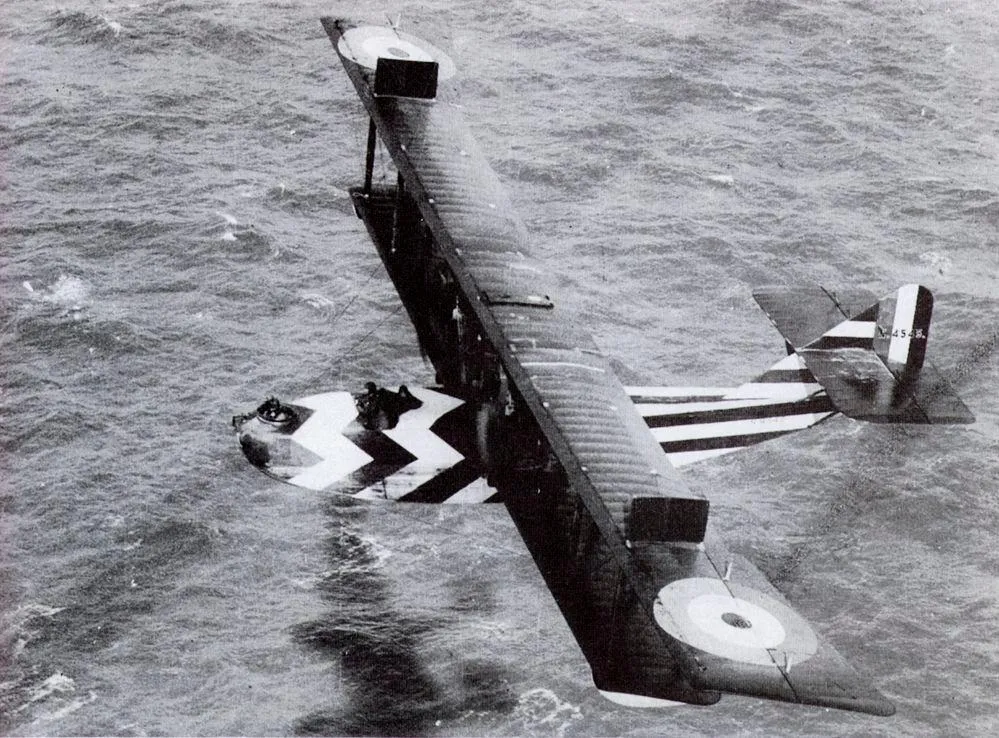

Behrens is more skeptical of the direct influence of the Modernist art style: “The artists who first studied camouflage were largely academically trained, and in some cases—Abbott Thayer in particular—were far more influenced by examples of camouflage in nature.” Whatever the origin, dazzle camouflage certainly harnessed similar effects of Cubism, in which strong, geometric shapes around a known form make the eye skitter. On aircraft such as the Felixstowe F.2A seaplanes, bizarre colorations in stripes and zigzags borrowed this artistic style to create confusion (see photo, bottom of p. 30). Instead of concealing an aircraft, the dizzying patterns made it difficult for gunners to get a lock on its distance and heading. Oddly enough, the graphics often helped by making the aircraft more visible; since fellow pilots could easily identify the strange markings, friendly fire was reduced, and sea rescuers had an easier time finding downed Felixes.

The method that Brush and Thayer advocated, meanwhile, was countershading, something they observed in the animal kingdom. Usually, the sun shining on an object below creates a shadow underneath, which gives definition to the object and makes it easier to see. Many prey species, such as deer, have light-colored underbellies, which creates an illusion that diffuses the shadow to anyone looking at it. This makes the prey appear more flat than three-dimensional, and less obvious to a predator. Thayer and his son Gerald captured this effect hauntingly in their nature paintings. Similarly, aircraft with lighter undersides should also flatten, when viewed at altitude by enemy aircraft.

While working on the family monoplane, George and Mitty experimented with a related but slightly different technique called counter-illumination. The idea was to make the aircraft as bright as the surrounding sky—in effect, it would be transparent. George’s first attempts were to apply varnished silk to the wings. “While this gave a nearly ‘invisible’ effect, the material (it was before the day of plastics) did not prove sufficiently durable,” explained his daughter Nancy Douglas Bowditch in her biography about her father’s artistic pursuits. Mitty tried punching holes through the linen wings to let light from above pass through and, as she wrote in her patent, “become diffused and practically obliterate all contrasts of light and shade on adjacent surfaces.” She also positioned lights inside the aircraft and on the fuselage to further illuminate the parts that functioned better without holes. She often tested the experiments by flying her “invisible” airplane around their Long Island and New Hampshire homes.

Though the counter-illumination inventions Mitty patented were never put into production, the spirit of the idea was reborn during World War II. A now-declassified 1946 report by the National Defense Research Committee explains that trials were conducted in which lights were attached to a B-24 Liberator’s nose and its wing’s leading edge to reduce its head-on visibility, after determining that the amount of power to light up the entire underside of an aircraft would be prohibitive. Though the Yehudi (slang for “the little man who wasn’t there,” according to the report) camouflage proved successful in the tests, radar and stealth technology advanced so quickly that the technique never made it into practical use.

As World War II began, a new generation of camofluers were recruited, with artists like Color School abstract painter Ellsworth Kelly influencing techniques. Kelly was a member of a U.S. Army tactical deception unit called The Ghost Army. Grumman Hellcats and German Messerschmitts flew and fought in the skies, using updated versions of Thayer’s countershading system.

As for Mitty’s invisible airplane, it recently reappeared. In 2011, a tattered wing, the seat, the landing gear, and the suspension wires were discovered in a barn in New Hampshire. The pieces are now exhibited at Pennsylvania’s Eagles Mere Air Museum. However, no photos showing Mitty’s stealthy test flights have ever shown up. Perhaps the disappearing act worked too well.