Bait and Switch in Libya

Naval aviators push Qaddafi’s buttons in a 1981 exercise

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Above-Beyond-illustration-FLASH.jpg)

In March 1981, after being stationed in the Caribbean for training exercises, the aircraft carrier USS Forrestal steamed to the Mediterranean on a six-month deployment. As a naval aviator and administrative officer, I flew anti-submarine/anti-ship Lockheed S-3A Vikings off the Forrestal with the VS-30 Diamond Cutters squadron.

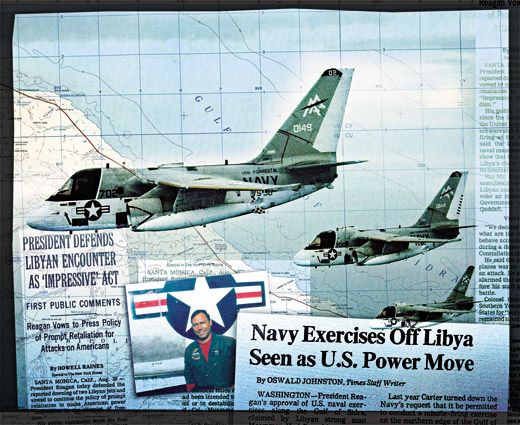

U.S. relations with Libya had become increasingly tense since the previous year, when Libyan fighters had fired at a U.S. Boeing RC-135 reconnaissance aircraft over the Med. Muammar Qaddafi, murdered last year by his own countrymen, had been in power for a dozen years and for the last eight had claimed the entire Gulf of Sidra as Libyan territory. At the time of our deployment, he threatened a military response if either aircraft or ships crossed his “Line of Death.” The United States, its allies, and the United Nations, through the Freedom of Navigation program, all refused to recognize Qaddafi’s claim.

Today we know that President Reagan had authorized the exercise on which we were about to embark, which would simulate an air/sea incursion in the gulf: We would radar-target our own ships, and they, in turn, would defend against fake missile attacks.

Late one night in August, the USS Nimitz and the Forrestal took up station in the gulf, about 100 miles off Libya. Our mission was to test Qaddafi’s line by observing Libya’s response to a U.S. Navy jet racing around far inside it, but (just barely) outside a 12-mile zone of internationally recognized territorial waters. To prepare for the possibility of a battle, most of the carriers’ non-essential aircraft were flown to Naval Air Station Sigonella, Sicily, to make space for fighters to trap, refuel with engines running, and re-launch.

Even before the exercise began, we got an ominous call: Three MiG-25s were approaching Nimitz from the Libyan coast. Combat air patrol F-14 Tomcats from the Nimitz and F-4 Phantom IIs from Forrestal escorted them from the area without incident. Watching from the pilots’ ready room, we surmised that the MiGs, lacking sophisticated radar, were trying to pinpoint our location.

Next, a wave of 70 aircraft approached—MiG-25s, -23s, Sukhoi Su-20s, and -22s. The chuckles and high-fives in the ready room turned to frowns. “Are you kidding me?” someone said. “I didn’t think they even had 70 airplanes!”

Soon a third flight approached, flying high and fast, but F-14s and F-4s headed the group off without incident. Some combat air patrol pilots boasted they’d finally seen some action on what had been a fairly uneventful tour.

In the pre-dawn hours of August 19, seven pairs of F-14s and F-4s launched from the Nimitz and Forrestal, orbiting 60 miles off the coast to protect the long-awaited “missile exercise” aircraft from Libyan harassment.

At 5:30 a.m., while I finished the preflight checks of our S-3A, call sign “Diamond Cutter 702,” the squadron executive officer, as pilot in command, received the final mission briefing. I copiloted, handling radios and navigation.

The XO, a senior aviator and respected leader, was an obvious choice for the mission. I may have been selected because I spent 1975 at the U.S. Army Defense Language Institute, studying Turkish and some Arabic, and had spent two years in a pilot exchange program with the Turkish naval air force (where I earned the call sign “Turk”), teaching pilots in the Grumman S-2E Tracker. Apparently our carrier air group commander thought my language skills might be helpful that day. I hoped he wasn’t assuming that if we ended up having to parachute into Libya, I’d win over the locals with my language skills: I was fluent in Turkish, but the extent of my Arabic would have probably landed us in a bar or a bathroom.

At 0600, we taxied to catapult number one. Once hooked to the catapult and at full power, the XO snapped a salute to the shooter, who signaled us to launch. We blasted from zero to 170 mph in under three seconds.

About 20 minutes later we reached our operating area off the Libyan coast. Our mission was fly low—300 feet above the waves, to avoid alerting Libyan radar—then pop up to 10,000 feet once we were 15 miles from shore, and stay over international waters. We would fly a racetrack—essentially a holding pattern—parallel to the shore, just to see what would happen. This turned out to be nerve-wracking: Our unarmed S-3A had no radar warning receiver (“fuzz buster”), no radar-confusing chaff, and no flares to defeat heat-seeking missiles—defensive systems added shortly after to the S-3B model. We expected to be detected by Libyan radar, but we also needed to make it clear that we had no intention of flying into Libyan airspace.

Minutes after we leveled off at 10,000 feet, an airborne early-warning E-2 Hawkeye radioed that two Su-22s were lifting off from Okba Ben Nafi Air Base, near Tripoli, and to stand by. This is not comforting advice when supersonic enemy fighters are headed toward your unarmed airplane. “Uh, stand by for what, exactly?” I asked the XO.

A moment later, the Nimitz Combat Information Center radioed, “Diamond Cutter 702: Buster North, I say again, Buster North!” The naval aviation manual translates “Buster” as “To make haste by all available means.” As the XO pushed the throttles forward and banked north, I replied: “Diamond Cutter 702, roger Buster North.”

We immediately activated the direct layer control system, which deploys huge spoilers on top of the wings, eliminating almost all lift. The DLC is unique to the sub-hunting S-3, designed to allow us to descend quickly from high altitude, then attack a submarine before it can evade us. Or, in this case, try to evade Mach 2 enemy fighters. Our 50,000-pound Viking dropped at 10,000 feet per minute.

At 5,000 feet, we needed to start pulling out of our dive so we could level off at 300 feet without inadvertently “splashing,” which would have ruined our whole day. Our dramatic descent, and the resulting sudden loss of radar contact with Libyan controllers, was likely the source of Qaddafi’s later claim that his fighters had shot down an American aircraft.

Meanwhile, speeding along at 450 mph 300 feet over the gulf, fuzz-buster-less, we had no way of knowing if or when the Libyans had fired at us. Then again, as slow and defenseless as we were, we really didn’t want to know exactly when a missile might hit us.

Thankfully, at the same time, the Hawkeye directed two F-14s, Fast Eagle 102 and 107, flying combat patrol off the Nimitz, to “turn and burn, expedite intercept.” Once the Libyans realized the Tomcats were headed their way, the Sukhois turned to engage head-on.

The first Sukhoi fired an AA-2 Atoll short-range, heat-seeking missile at the first F-14. It missed, and the Sukhoi tried to escape. The Tomcats, without being cleared to return fire by the E-2C Hawkeye, followed combat rules of engagement on self-defense: They pulled hard 180-degree turns, dove on the Sukhois’ tails, and fired AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles.

At this point, we were busy thinking supersonic thoughts, hoping to stay ahead of the Su-22s—until we heard “Fox-2 kill” and then “Fox-2 kill, trailing chute,” which meant the F-14s had knocked out both Sukhois, and the pilots had spotted one parachute.

Our mission was complete. Because the Forrestal’s air boss wanted to keep his flight deck free of traffic in case a real battle ensued, we continued north past the carriers to land at Sigonella.

Taxiing in, I was surprised to see fellow aviators who had flown off the ship before the operation sprinting out to meet us, shouting questions. Because they had been out of the range of ultra-high-frequency line-of-sight radio, they had heard very few details.

We did our best to respect the secrecy of the mission, giving only a general idea of what we’d done: just sort of monitored the situation.

Back then, our role as bait was classified. The entire operation had a bit of a covert feel, so when I returned Stateside, I was surprised to see names of the F-14 crews and squadrons in the news. I was perfectly happy that the role of our S-3A remained under wraps for years. Little was said of the Forrestal’s role—the Nimitz and its Tomcats were always the stars.

On a sunny Saturday two decades later, I took my grandsons to the National Air and Space Museum, where we toured a mockup carrier air operations center. On the ready room briefing board was the August 20, 1981 New York Times account of the Gulf of Sidra incident. Neither the Forrestal nor our Viking was mentioned, but the clipping, enshrined in the Museum, was, to me, a confirmation of the small role we played in the event.

A naval aviator and NATO instructor from 1966 to 1988, Tom “Turk” Sanders flew the S-2 Tracker, S-3 Viking, TA-4 Skyhawk, and SH-3 Sea King helicopter. He lives in Marietta, Georgia.