Barnstorming in the Blood

One of the world’s most inventive pilots makes everything old look new again.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Barnstorming_F_1_AUG2010.jpg)

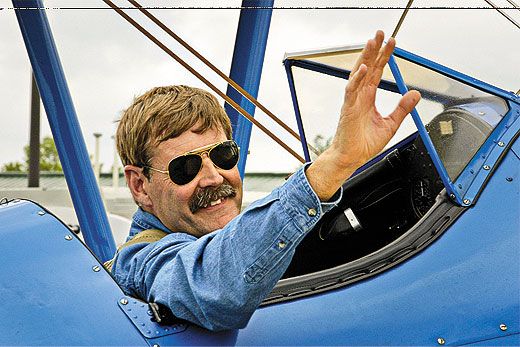

The best place to watch John Mohr fly his Stearman would have been up against the airshow fence, where I could have heard the crowd’s gasps when the airplane, which had disappeared behind trees, suddenly reappeared in a vertical climb.

Instead, I was taxiing across the ramp because my performance was after his, but I did put on the brakes when an excruciatingly slow roll near the ground caused his engine to quit and flames to shoot out of his exhaust stack and down the side of his fabric fuselage. Even though I knew it was all part of the act, I still held my breath.

I was amazed by how Mohr could squeeze square loops and double snap rolls out of an underpowered, drag-ridden, 2,400-pound biplane at an airport with an elevation above 3,000 feet. The Stearman seemed to defy the aerodynamic laws of drag and air density as it flowed from one maneuver to another without the panting you’d expect from a heavy airplane on a hot August day.

The 220-horsepower PT-17 Kaydet, a classic that Boeing manufactured between 1940 and 1944 (Mohr’s was built in 1943), was designed as a primary military trainer for the basics: takeoffs, landings, climbs, glides, and elementary aerobatics. That is what a Stearman, ordinarily, still does: the basics. However, watching Mohr, I could see a flying dimension beyond the world where most pilots fly. It is a world in which finesse, intuition, and daring allow the more gifted pilots to do seemingly impossible things with an airplane like a stock Stearman. On its last pass the airplane looked like a cock-eyed crab, scooting sideways down the show line in the direction of its lowered left wingtip. Jerry Van Kempen, of Alexandria, Minnesota, knows Stearmans and the pilots who fly them, having spent 18 years as the Red Baron Stearman squadron’s announcer. He says, “John Mohr is the best Stearman driver in the world.”

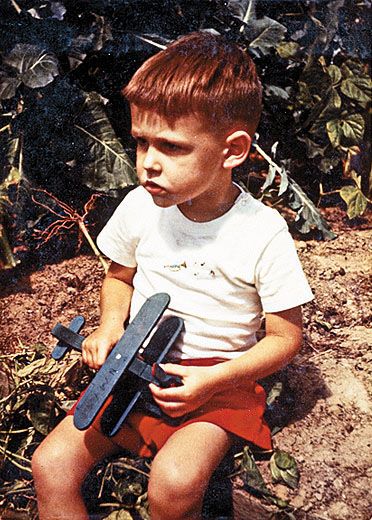

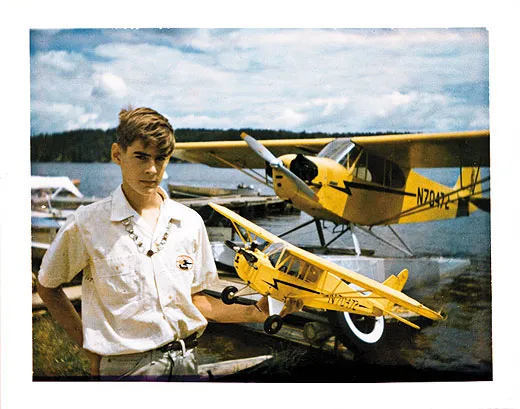

Mohr was born into a flying family and lived on Crane Lake at the northern Minnesota border. He grew up in the family airplanes, on floats and skis. His first solo flight was in their float-equipped J-3 Cub. As he heard the echo of his father’s floatplane taking off each morning loaded with campers, hunters, or fishermen bound for nearby canoe and wilderness areas, his grandfather told him flying stories: about the SPAD he brought back in a crate from France and transformed into a parasol-style monoplane, about the Curtiss Jenny he learned to fly after World War I, and about barnstorming southern Minnesota and Iowa with a Waco 10.

When Mohr was 17, he built his first of three kit helicopters, a single-seat Scorpion. It came with flying instructions, and following them, he taught himself to fly it. When he was 19 or 20, he bought a 145-hp Cessna 172 and converted it to a floatplane, but the black-and-white photos of biplanes on his grandfather’s walls called him back to the Golden Age. So three years later, in 1975, he bought a Stearman and restored it to its original Army Air Corps yellow and blue.

“At Oshkosh I had seen the guys in the big biplanes with all their noise and smoke. Walt Pierce, Jimmy Franklin, and Bob Lyjak with his taper-wing Waco and his double snap, right on takeoff. They really impressed me,” says Mohr. “I wanted a big biplane and I wanted to fly like they did.”

With the Stearman, he was ready to begin his own brand of barnstorming.

A close friend scoped out fairs, festivals, and farmers’ pastures in northeastern Minnesota where Mohr could sell rides on the weekends. “He’d get the people in and I’d climb up to a couple thousand feet,” Mohr says. “I would do a loop, barrel roll, hammerhead, and snap roll, then would spin back down on a ride that lasted all of three minutes or so. Everybody would get out smiling, cheering, and laughing, and the next one would be ready to jump in. Nobody wanted a straight-and-level ride once the fun started. That is how I got good at acro.” He was having fun, and making more money than he earned in the flight operation he had back in Orr, Minnesota, where he also had a wife and a new baby. “During the week I was starving,” Mohr recalls, “doing flight instruction, generating charter business, and trying to get hired by the airlines.” By the time he landed a job at North Central Airlines, he had gained local fame and teamed up with nearby pilots to fly airshows. Today he is a captain for a major airline, but ever since those days of selling hops in his Stearman, Mohr has been a steady airshow performer.

“Once, at a show up in Longville,” recalls Jerry Van Kempen, “the clouds were so low the ducks were walking and people were ready to leave, but after a while we heard the blub, blub, blub of John’s 220 [horsepower engine] headed our way. He has never missed an airshow.”

While he developed his Stearman routine, Mohr worked with a friend, Dave Simonson, to invent another startling act. Airshow performers were doing only car- or motorcycle-to-airplane transfers. When Mohr and Simonson tried an aerial transfer they saw why. Even in still air, a stuntman dangling on a rope ladder from a J-3 Cub swung dangerously close to the high arc of the Stearman’s propeller. Then one day in 1993, while flying his Enstrom helicopter beside the Stearman, he wondered how close he could get to the airplane without causing a midair collision. “I started messing around with my approach angle until I finally found the sweet spot where I could approach the airplane and actually put a skid on the top wing. Suddenly I thought, Wow, this is the transfer act! ” After some experimenting, they became comfortable enough with the flying to ask another friend, Royce Baar, to join them as the stuntman who grabs the helicopter skid and is lifted from the airplane.

Mohr didn’t know, and neither did Simonson, that eight or 10 years earlier, Hollywood pilot Craig Hosking had landed a helicopter on a DC-3 wing for the TV show “Incredible Sunday.” When the pair started performing the transfer, they became the first to turn an airplane-helicopter transfer into an airshow act.

Mohr pitched the routine at the International Council of Air Shows annual convention, where airshow promoters shop for new acts. Most people looked at the video, shook their heads and said, “If you’re still around in two years, maybe we’ll consider you.” But they got several bookings for the 1994 season, and gradually they became the rage. In 2000, Mohr Barnstorming won two national prizes: the Bill Barber Award for Showmanship and the Art Scholl Showmanship Award. By then Mohr had gained international attention for his solo Stearman act, which he says is the more challenging to fly.

All but a small portion of Mohr’s performance is flown close to the ground, the tops of his looping-type maneuvers reaching no more than 400 or 500 feet. His flying margins are narrow; he relies on his skill, experience, and something called ground effect. During flight, wingtip vortices and the resulting downwash produce drag; when an airplane is no more than a wingspan away from the surface, the ground partially dissipates the vortices, reducing drag and boosting airspeed.

Probably no one is more impressed by Mohr’s flying than other Stearman owners, and sometimes they refuse to believe that his airplane is a 100 percent stock machine. Recently at the Sun ’n Fun fly-in at Lakeland, Flo-rida, a new Stearman owner questioned him over and over. “I watched you fly in this and you didn’t climb for altitude,” the man said. “You did a slow roll and a snap roll right on takeoff, then a hammerhead. My plane won’t do that. What have you done to get that kind of performance?”

“Nothing,” Mohr said. “I have 10,000 hours in the airplane. It’s skill and experience. It’s not the airplane.”

This is Mohr’s trademark. What started as necessity—he couldn’t afford more power to begin with—became virtuosity. He had to learn, he says, to fly the wing, not the engine. “Nobody else gets as much out of a 220-hp Stearman as I do,” he says. “Even guys with 450s are flying higher and don’t do as many maneuvers or put their shows together the way I do.”

It is easy to see why fans expect a showplane to be modified. Many show pilots spend huge amounts of money to get more performance. In the past, prominent Stearman show pilots, such as Joe Hughes and the Red Baron Squadron, doubled and tripled their engines’ output for wingwalking and formation acts. They added streamlined cowlings, nose cones to cover the propeller hubs, fairings on wheels, and ailerons to their top wings to boost roll rate. The stock Stearman has none of this. With all its wires, struts, knobby tires, prominent exhaust pipe, and seven cylinders sticking out in the wind, it is as streamlined as a pine cone.

Mohr stopped flying the airplane-to-helicopter transfer act after about eight years because crew, maintenance, and insurance became prohibitively expensive. A few years ago, he revived it, partnering with Roger Buis, who flies the “OTTO The Helicopter” comedy act, and longtime stuntman Todd Green. The three of them ham it up, dance around, fly side-by-side hammerheads with Green hanging by his elbow from Otto’s landing skid until Buis lowers him into a cloud of smoke on the ground.

A barnstormer’s grandson, Mohr grew up thinking of new ways to fly old airplanes. He’s still thinking, and developing the next act, which for now he is keeping behind his own smoke screen.

Writer and airshow pilot Debbie Gary has enjoyed writing about the best in her profession in Air & Space’s trilogy of features on airshow performers.