Barnstorming the Beltway

How a homebuilder’s determination won liberty and experimental licenses for all.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/beltway_388-may06.jpg)

After World War II the Civil Aeronautics Administration, expecting a boom in private flying as pilots returned from overseas, issued regulations governing the production of light aircraft. The expectation was that new airplanes would be built in factories and meet federal guidelines. Private citizens who wanted to build their own aircraft were left in limbo. Homebuilts were not expressly forbidden, but licensing limitations were so restrictive that such airplanes would have no practical use.

This didn’t go over well, particularly in Oregon. In the pre-war years it had been possible to build and fly airplanes there on a state license, without government interference. Pioneers like Oregon farmer and mechanic Les Long inspired small groups of young men who wanted to fly. They built—and re-built—small airplanes in barns and flew them from pastures. It was exciting stuff, especially in the dreary years of the Depression. Now, it looked like bureaucrats in Washington, D.C. were going to kill the fun.

In 1947, George Bogardus, from tiny Troutdale, Oregon, wanted to prove that homebuilt airplanes deserved better. He refurbished a single-seat, 65-horsepower airplane built before the war by Oregonian Tom Story. He finagled a special permit to fly the airplane, now christened Little Gee Bee, to Washington, D.C. (The airplane had no relation to the famous Gee Bee racers built by the Granville brothers; George Bogardus may have liked the play on his initials.)

His flight must have been quite an adventure. Sixty-five horsepower is pretty minimal for the mountainous West, and the rigid seat that Story welded into the airplane must have tortured the six-foot-one Bogardus. Stopping along the way to recruit members for what he called the American Airman’s Association, he landed safely, eight days later, in Deer Park, Long Island. From there, he and other members of the group flew to Washington, where they lobbied the CAA to write regulations making it legal to build one’s own airplane.

He was politely received and some temporary provisions were enacted. Not satisfied, Bogardus repeated the trip in 1951. Finally the CAA, (which became the Federal Aviation Administration in 1958) wrote a provision specifically allowing individuals to build and license airplanes in an “experimental” category for their own “education and recreation.”

His mission accomplished, Bogardus returned to Oregon, carved out a tiny airstrip on his property, and then dismantled Little Gee Bee and stored it in a shed. Increasingly reclusive, he faded from the aviation scene. His American Airman’s Association never developed, but a similar group, the Experimental Aircraft Association (Bogardus was said to regard it as a rival), has grown into one of the largest aviation organizations in the world.

Bogardus died in 1997 and, surprisingly, left his estate to his local EAA chapter. One chapter member, Dick VanGrunsven, who had as a teenager been enthralled with airplanes, had often flown his Taylorcraft onto Bogardus’ strip for visits. The designer of

a line of kit aircraft,VanGrunsven headed a crew that cleaned up the property. It was a major task; Bogardus was a bit of a pack rat. After removing airplane parts, sundry mechanical debris, and towering piles of old magazines, they found Little Gee Bee where Bogardus had stored it, 45 years earlier.

The airplane was in rough shape. The engine was disassembled and the pieces thrown into several boxes. The fabric covering was nearly gone; it survived only on one wing and part of the other. The wheels were badly corroded and the tires were rotted beyond redemption.

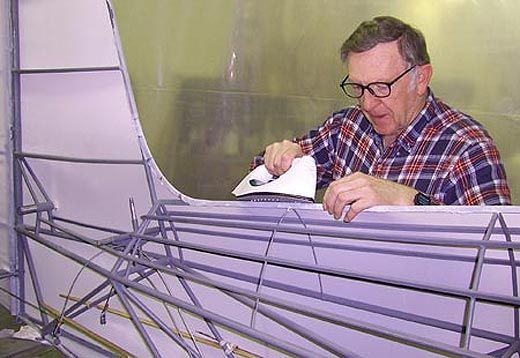

Eventually, Little Gee Bee was moved to VanGrunsven’s shop in North Plains, Oregon. There, Dick, his brother Jerry, and a band of volunteers met every Saturday to rebuild it. One of the first to show up was Mike Story, son of the original builder.

“Little Gee Bee evolved from one of Les Long’s designs,” says VanGrunsven. “In the ’30s my father flew from Long’s field—it’s just a few miles from here—and he always mentioned Les’ talent with great respect.

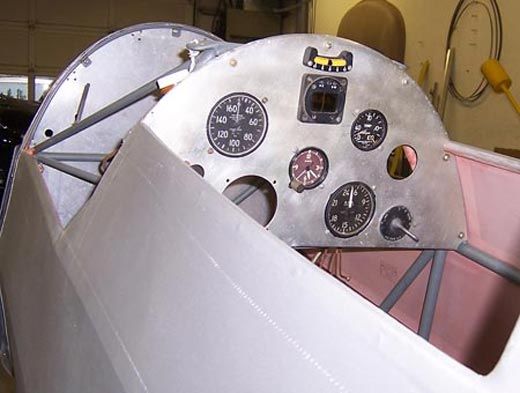

Inspecting this airplane confirms that. It’s an elegant design, with a very light, strong structure that gets the best out of the small engine. The steel-tube fuselage is beautifully welded…. Tom Story was an artist with a torch. Everything about the airplane is simple, but it all worked and worked well.”

“My dad was a builder,” says Mike Story. “He built about 14 airplanes and a complete car, but when he was through, they’d sort of go away. Then he’d just start building something else.”

After the fuselage was sandblasted, repainted, and recovered, the corroded aluminum leading edges of the wings were replaced and the rotted wood ribs rebuilt. The Sensenich Propeller Company reconditioned the wood propeller. No original tires or wheels could be located, so another VanGrunsven brother, Stan, restored the original wheels and machined adapters to accommodate Piper Cub tires.

By this spring, Little Gee Bee was almost completely restored and destined for a spot in the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Dick VanGrunsven believes the aircraft deserves the honor. “By itself, it’s just another little airplane, but in the historic sense, it’s a heck of an ancestor,” he says. “About one out of five airplanes registered today is amateur-built—even SpaceShipOne is registered in the Experimental category. They can all be traced back to Little Gee Bee.