Bazooka Charlie and the Grasshopper: A Tale of World War II

The most famous small airplane of the war is about to fly again.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a6/fb/a6fb012e-6460-4900-87f0-6c96788286ea/03d_am2020_-_img003_live.jpg)

Joe Scheil is a numbers guy. When he sees an interesting airplane, he looks for its serial number in an online database or published reference work to learn what he can about it. He adds the information he finds to one of several Excel spreadsheets he has created with details on hundreds of airplanes organized by their serial numbers. In 2017, while reading an article in the Experimental Aircraft Association’s magazine Warbirds of America, Scheil came across a photo of a famous World War II Piper L-4 Grasshopper, serial number 43-30426, and decided to find out more.

The article was about Charles Carpenter, an L-4 pilot who became known as “Bazooka Charlie” for his exploits against German tanks. The Grasshopper—a Piper Cub as a civilian—was flown during the war as a liaison and observation airplane, but Carpenter, war-weary and homesick, became dissatisfied with flying as an artillery spotter, scouting ahead of the advancing 4th Armored Division of General George Patton’s 3rd Army. Instead, he bolted six M1A1 bazookas on the wing struts of his Piper and rained fire on Panzer columns. “It was like a sparrow trying to attack an elephant,” says his daughter, Carol Apacki, who had written the article Joe Scheil read, “except this sparrow had fangs.”

Carpenter wasn’t the first pilot to hang weapons on an L-bird—as liaison airplanes like the Aeronca L-3, Stinson L-5 Sentinel, and the L-4 are known—but he was almost certainly the most effective at using them. In October 1944 alone, he destroyed four tanks and an armored truck. On the side of his airplane, he painted “Rosie the Rocketer,” a tribute, Apacki says, to the women working in aircraft factories back home, who were nicknamed Rosie the Riveter.

Besides picking out the Piper’s registration number, Scheil—an airline pilot and Cub owner who reads a lot of military aviation history—saw something else in the photograph of Carpenter and his airplane: a reminder of another photo, often included in histories of World War I. “It’s the picture of Frank Luke in front of his SPAD, the day before he died,” says Scheil. Luke, the first pilot to receive the Medal of Honor and at the time of his death the country’s leading ace, was, like Carpenter, unconventional and aggressive in combat. Scheil says Luke and Carpenter had the same casual pose and the same sad look. By the time Carpenter’s photo was taken, “all the ineptitude, naiveté, and bewilderment of the Americans as we were getting ourselves killed in North Africa” was gone, Scheil says. What he saw in Carpenter was the grind of the war after Normandy and the grief borne by airmen who had witnessed its horrors.

Charles Carpenter and his small airplane were also similar in some ways. Innocent in its early days, the Piper Cub was painted sunny yellow with a black lightning bolt running the 22-foot length of its fuselage. Nothing beats a Cub on a warm summer afternoon with the side door open: Pilot and passenger can watch the world float slowly by.

With a gross weight of 1,220 pounds, a cruising speed around 80 mph, and Model T simplicity, the Cub gently introduced thousands of pilots to flight from the late 1930s to 1944 through the U.S. Civilian Pilot Training Program.

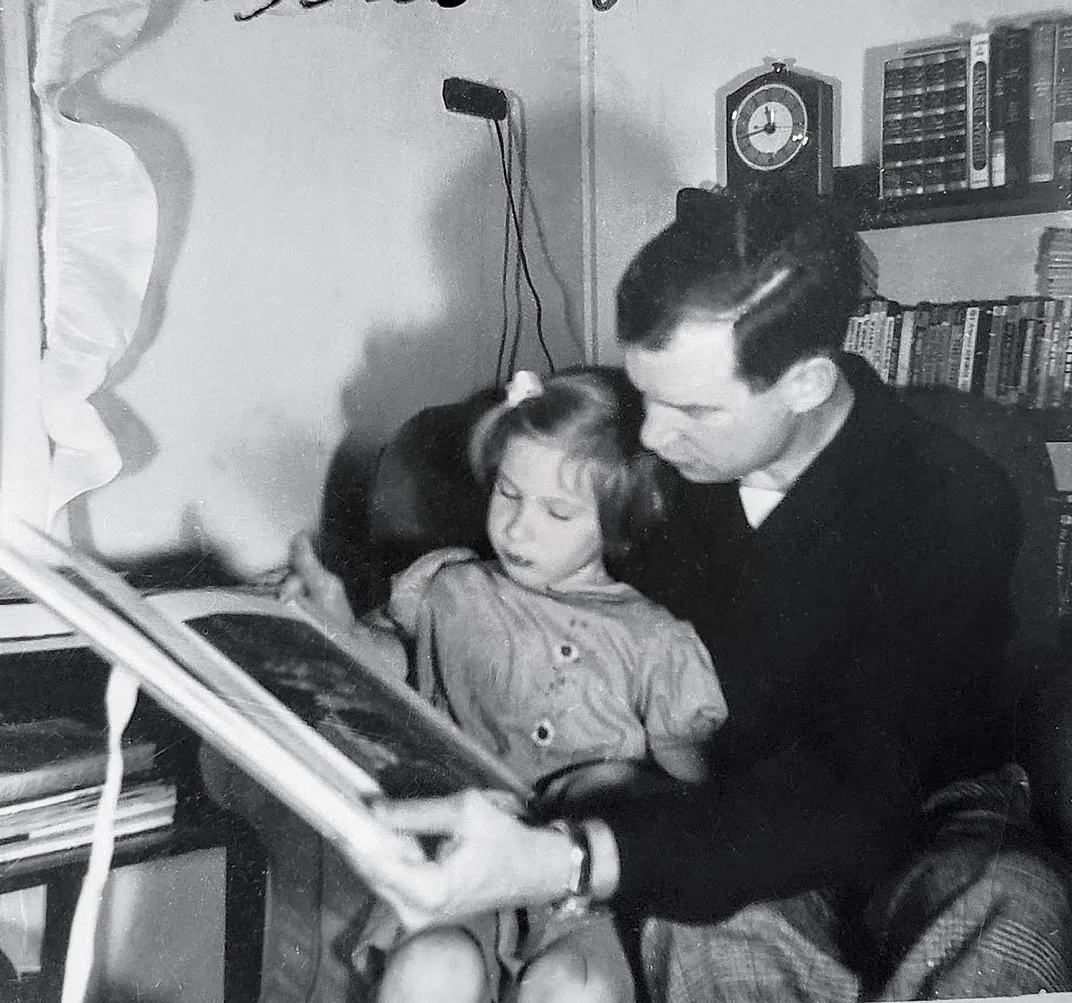

Carpenter could also be considered a trainer. Before America’s entry into World War II, he taught history in a Moline, Illinois high school. After the war, “In the summers, he ran a boys’ camp in the Ozarks,” his daughter writes in Warbirds, “a camp that focused on teaching outdoor skills and building character.”

When the war began, the Cub traded its yellow paint for olive drab, and Carpenter enlisted in the U.S. Army, commissioned as a second lieutenant. Flying at an altitude of 1,500 feet, the L-4 Grasshoppers could speed the advance of tank columns by reporting the positions of the enemy. Initially German soldiers feared giving away their positions by firing on L-birds, but the calculus quickly changed. Once Carpenter started firing bazookas, the Germans saw him as a threat. “Every time I show up now, they shoot with everything they have,” he told a Stars and Stripes reporter. Even before Carpenter turned his L-bird into an attack aircraft, spotter pilots were in danger. In June and July 1944, General Omar Bradley’s 1st Army lost 49 artillery spotting aircraft and 33 pilots. Flying at low altitude made the pilots vulnerable even to light anti-aircraft fire.

Watching mayhem from his 1,500-foot perch and barely escaping gunfire eventually took a toll on Carpenter. In a poem he wrote after the war, “Incident in the Woods,” he tries to capture the impact of combat on vanquished and victor alike. He describes coming upon an enemy officer tending to a soldier who had been shot: “The soldier dead, the man had returned/ To save some seeming trifle./ It was a baby thing, blue, and partly burned./ He folded it and kicked his loaded rifle./ I led him from that torn and stinking spot;/ May fire and grassy time soften memory./ Willing guards took him at the prison lot,/ And smiled, and wrongly guessed me free.”

In early 1945, Carpenter was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease (a type of cancer), given a prognosis of no more than two years, and sent home. (Instead, he lived another 21 years.) His airplane was assigned to another pilot. When the hostilities ceased in Europe, Piper L-4 aircraft, which had cost the government only $2,500 each, weren’t worth shipping home; they were either scrapped or sold as surplus. The Piper L-4 flown by Carpenter met one of those two fates. Until Scheil decided to look into it, no one cared which one.

Within hours of reading Apacki’s article about her dad, Scheil found that the L-4H, serial number 43-30426, had been left in a German surplus yard in September 1946. He first searched a list of military aircraft serial numbers on joebaugher.com, a website familiar to most warbird fans and packed with information about U.S. military airplanes. And there it was: On the site, the military serial number is linked with the manufacturer’s serial number 11717. With that manufacturer’s number, Joe Baugher’s source—he also lists on his website the people who email him information—found that after the war, the airplane was registered in Switzerland as HB-OBK and in April 1956, re-registered in Austria as OE-AAB. With further research, Scheil learned that Heinz Wullschleger of Olten was the first to register the Cub and that when the registration changed in 1956, the aircraft, sporting yellow Cub colors, became part of the Austrian Aero Club in Vienna, where it towed gliders.

For a number of years, the little Piper flew as a civilian until, as the second aircraft ever registered in Austria (signified by the designation AAB; AAA being the first), it was acquired by the Österreichisches Luftfahrtmuseum at Graz Airport. That’s where it was in 2017, when Scheil tracked it down. Bingo. Scheil called Rob Collings.

One of the foremost warbird collectors in the United States, Collings is the chief executive officer of the nonprofit Collings Foundation, which has supported the restoration and display of two dozen historic warbirds, including a Curtiss P-40 that had been in a hangar at Pearl Harbor on the day of the Japanese attacks and a Supermarine Spitfire that had flown 116 combat missions. The foundation also supports the Wings of Freedom tour, which sells rides aboard the P-40, a P-51, and several large bombers.

Scheil, one of the pilots who had flown the B-17 and a B-24 on the Wings of Freedom Tour, knew that Collings was looking for a combat aircraft that had seen action during the war.

“There are none that are obtainable,” Scheil says. “There’s no P-47 from the Eighth [Air Force] or the Ninth. We were looking for something that could capture the fight from Normandy to Germany—for an aircraft that was doing air-to-ground work.” Surviving P-51 Mustangs had all been spoken for, Scheil says. “So when this Cub showed up with an unknown number of tanks and armored cars killed, it was oddly enough the most destructive aircraft that we had extant from the ground war across Europe.”

Scheil says Carpenter and his Grasshopper are credited with stopping a German counterattack in one battle. “That was a very significant accolade paid in 4th Armored Division records to a liaison aircraft,” he says.

Rob Collings traveled to Graz, Austria to examine the Piper Cub then registered as OE-AAB.

“When I first saw the L-4 in person it had recently been recovered and was being restored as a static display,” says Collings. “We didn’t know too much about it because it had fresh fabric on it, and they weren’t keen to let us start cutting into it.” The museum was unaware of the airplane’s service in World War II, but Collings could see the serial number on the data plate. Not until the airplane was returned to the United States and stripped to the bare frame, however, could he confirm the parts numbers against Piper records.

In 2004, Colin Powers, the restoration manager for the Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum in McMinnville, Oregon, won a trophy for the restoration of a Piper Cub that had served in the Pacific. “I bought it in pieces,” says Powers, “and I thought it would be a fun project to do.” The trophy was awarded by the National Aviation Heritage Invitational, which for many years has invited vintage airplane owners to display their airplanes at the national air races in Reno, Nevada, where they’re judged for the authenticity of the restoration. (Powers is now a Heritage judge.) More than 200,000 people attend the races and stroll among the classics in the Heritage competition, and one morning during race week, Powers saw on his L-4 a business card that had been tucked in its door. It was from the Reno fire marshal with a note saying that he was the nephew of famous L-4 pilot Charles Carpenter. From him, Powers learned that Carpenter’s daughter lived in Ohio. When the Heritage Invitational went to the Dayton Air Show the following year, Powers invited Carol Apacki to visit the airplane. She had never seen a Piper L-4. “I had her get in it and she became very emotional,” says Powers. “She didn’t really realize how vulnerable her father was while he was flying. We became friends after that.”

Later, Powers re-restored the airplane and won a trophy from the EAA for Reserve Grand Champion Warbird. After Collings finalized negotiations with the Austrian museum, he chose Powers to restore the L-4 because of his experience (Powers restored two more L-4s after his first one) and because Powers had such a strong connection with Carpenter’s daughter. Rosie the Rocketer was packed into a cargo container in Austria, trucked to Spain, and loaded on a cargo ship to New Jersey. The airplane traveled by train across the United States and arrived in Powers’ Oregon shop in January 2019.

“Once we got it back to Oregon and had the fabric stripped off, we were just blown away,” says Collings. “We didn’t want to make everything perfectly new because what was underneath was in great condition. The original wooden spars still had great varnish on them. The ribs were bare aluminum but they were all clean. The grease pencil handwriting was there from the factory, with names and dates. These are things that you could never duplicate.”

With three L-4 restorations under his belt, Powers wasn’t expecting any surprises from Rosie the Rocketer, but he got a few. “Bullet holes,” he says. “One bullet had passed from the bottom through the leading edge of the aileron into the wing, went through the steel-plate hinge for the aileron, tore a big chunk of metal out of one of the ribs and exited out through the top of the wing. I’ve retained all of that [damage]; except on top of the wing, I’ll just put a patch where it exited.”

Powers also located a double patch on the front strut where the Army had patched both sides after a bullet had apparently entered on one side and exited on the other. Collings is intent on bringing the L-bird back to look exactly like it did in 1944. To do that, Powers has a long list of tasks.

“The airplane was modified,” he says. “The cowling and boot cowl and a lot of the instrument panel are all different and need to be replaced. They replaced the engine with a Continental C90.” As a glider tug, he says, it would have needed the increased power. “We have a period-correct, 65-horsepower Continental to install.”

They also replaced three of the instruments with German instruments. “Rob’s got a copy of the Piper build sheet,” says Powers, so he can determine what instruments were in it in 1944. “Keystone Instruments in Pennsylvania is refurbishing all the original instruments for us,” he says.

Finding six original M1A1 bazookas will be daunting. Powers is using photographs unearthed by Carol Apacki to guide him in mounting the bazookas. He knows they were mounted on a piece of plywood on the struts, but figuring out the proper angles is going to be trial and error.

“It gives me a lot of pride that I was asked to restore Rosie,” he continues, and says he hopes to fly it when it’s finished.

In an August 1944 letter home, Charles Carpenter wrote, “Lately I have been taking quite a few chances but my luck has been marvelous. Yesterday I got a bullet hole through the wing and hit a church steeple with one wheel. It was very little for what might have happened under the circumstances.”

More than 75 years later, Bazooka Charlie’s Grasshopper will fly again, to Oshkosh for the annual EAA fly-in and warbird judging. It is one of the last World War II veterans to return home, bullet holes and all.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/c3/59c3031e-5a1e-4ae8-8477-25b8a4a67b7e/03j_am2020_-_davidwhitworthphoto_live.jpg)