Beware the Black Widow

The P-61, the Beaufighter, and the first air war fought in the dark.

:focal(2168x1281:2169x1282)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2f/88/2f888235-2509-4e97-8762-3798a5f584b5/03c_aug2016_p61_nightprepmidnightmickey_mh_live.jpg)

Vladimir Pavlecka had a message for his boss, Jack Northrop. It was October 1940, and a U.S. Army Air Corps colonel had summoned Pavlecka, Northrop’s chief of research, to a meeting at Wright Field in Ohio. The engineer was instructed to commit to memory—he could take no notes—specifications for a secret aircraft. This “Night Interceptor Pursuit Airplane” included an unnamed device that could “see and distinguish other airplanes” in total darkness. From the tone of the meeting, Pavlecka concluded that accepting the project wasn’t an option. It was an order.

The Northrop Aircraft Corporation, headquartered in Hawthorne, California, was only a year old, operating principally as a subcontractor for larger aircraft makers, so it seemed an unlikely choice to commission for the development of the world’s first dedicated night fighter. However, established manufacturers—Lockheed, Grumman, Douglas—were already committed beyond their capacity to stocking the nation’s flying arsenal. Also, the military may have gotten wind of something: A month earlier, the British Purchasing Commission had quietly approached Northrop with specs for a proposed night fighter for the Royal Air Force. Having endured nightly hammering from German bombers during the Blitz, the Brits had learned that night fighting required an aircraft with special characteristics: a high ceiling to intercept intruders, extended loiter time to circle a defended zone slowly, and the firepower to take down big bombers before they reached their targets. And perhaps most important, that unnamed device.

In the first world war, darkness had been used to cloak airborne weapons. German Zeppelins, though awkward aerial punching bags by day, hectored England with bombing raids on moonless nights. Gotha biplanes also night-bombed London, inflicting even greater casualties. Though England fought back with searchlight-guided Sopwith Camels and anti-aircraft fire, the memory of high explosives raining out of the darkness was unnerving to the British as they learned that German belligerence and warplane production was ramping up again in the 1930s.

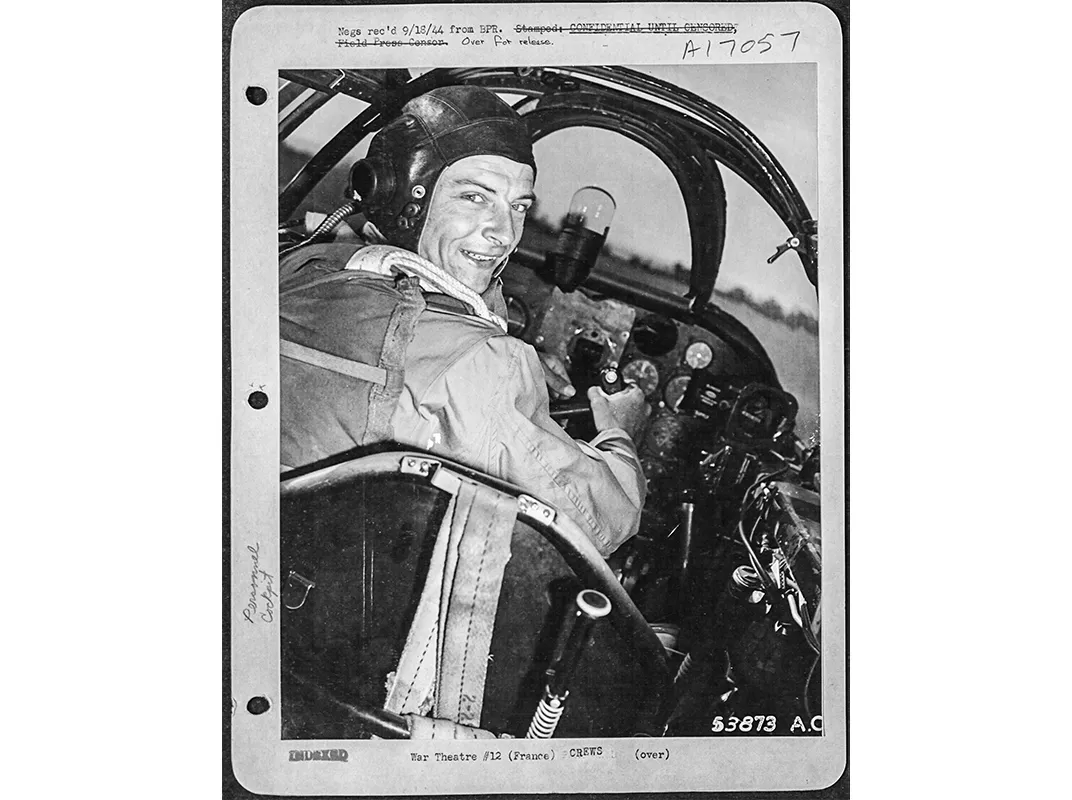

In the United States, where the airspace had never been violated, the ability to fight at night was a low priority. “It involved a handful of military pilots, trained by civilian airline pilots, who used conventional radio aids and standard flight instruments,” recounts Carroll Smith, destined to become the highest scoring night ace in the Pacific, in American Nightfighter Aces of World War 2 by Andrew Thomas and Warren Thompson. “The glaring weakness of this was that few of these pilots were able to fly without visual references to the ground.”

A few months before Pavlecka had his secret meeting in Ohio, a contingent of Army Air Corps observers had been sent to get an after-hours view of the Battle of Britain. A string of long-wave radar installations along the British coast pulsed the sky over the North Sea. On cathode ray scopes at ground centers, the American visitors watched electronic signatures of German intruders, and the twin-engine Bristol Blenheim night fighters the controllers sent to intercept them. Unknown to the Americans, the Blenheims were also equipped with then-classified radar to augment ground control guidance.

A month later, as part of a joint agreement to share military secrets, the British Technical and Scientific Mission arrived in Washington. British disclosures included the Whittle turbojet—one of the forerunners of all jet engines—and several hand-made, long-wave airborne radar sets. The United States agreed to sponsor research and development of microwave radar—more accurate and less glitchy than long-wave radar—at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The MIT Radiation Laboratory fast-tracked the first 10-centimeter-wavelength airborne unit, producing it in six months.

After his meeting at Wright Field, Pavlecka caught an overnight flight back to Los Angeles, and the next morning told Jack Northrop about the orders from Ohio. Noting the similarities between the Army Air Corps specs and the preliminary concept he had already sketched for the RAF night fighter, Northrop spent two weeks incorporating elements of both into a single aircraft, then personally took the plans to Wright Field. Within three months, Northrop had hired 125 engineers to work on the project, promising the military one experimental XP-61 in nine months and 12 service-ready YP-61s in 16. They were deadlines just begging to be missed; a P-61 didn’t enter combat until 1944.

Northrop’s P-61 design was medium-bomberish: 66-foot wingspan, two 2,000-horsepower engines, twin tail booms, three crewmen required. Its estimated fighting weight exceeded 29,000 pounds. (A fully loaded British de Havilland Mosquito fighter was only 17,700 pounds.) Pilots were often unimpressed at first: “I remember thinking, ‘She’s too big and clumsy to be a fighter,’ ” Smith wrote after the war. The airplane’s hefty specs were driven by its unique mission, but also by British influence. In Queen of the Midnight Skies by Garry H. Pape and Ronald C. Harrison, Northrop chief of aerodynamics William Sears recalls, “The configuration, armament, loiter capability, relatively short range, were all pointed toward the London defense situation.”

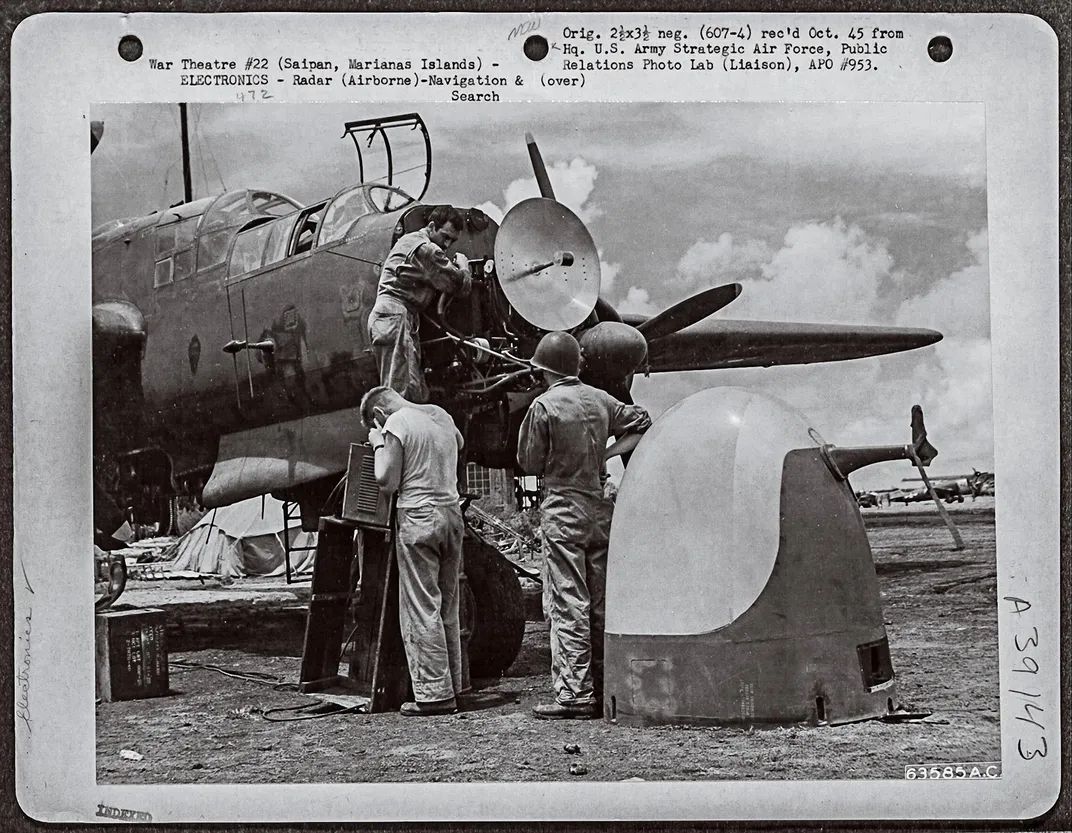

The pièce de résistance was the airborne microwave radar: enclosed in the nose of the aircraft, the spinning, 30-inch scanner-receiver dish antenna would sweep the sky with a knife-like beam. Using it reduced the ground echoes that plagued long-wave radar at low altitude, and the shorter wavelength enhanced accuracy, guiding interceptors to within 100 yards of intruders in total darkness.

The aircraft’s $180,000 price reflected the advanced technology and mission-specific engineering. But for the same price you could get two C-47 transports, or three P-38 fighters. Not everyone was on board with the big-ticket option. General Hoyt Vandenberg, famed commander of the Ninth Air Force, contended the mostly wooden Mosquito—some were eventually equipped with radar—offered more night-fighting bang for the buck. When the Northrop fighter arrived in Europe in 1944, Vandenberg predicted: “Little success can be expected.”

For nearly 18 months, Northrop engineers slogged through developmental delays and revisions, but the Army Air Forces couldn’t wait any longer to start training pilots. Night crews were volunteers, and the military had no problem recruiting candidates. “Their courage and resourcefulness will have to exceed, if possible, all that any pilot has ever had before,” wrote General William Kepner, commander of bomber support squadrons in England, to the director of night fighter training.

Most of the pilots selected had at least 100 hours flying B-25 bombers. Twin-engine experience was required, as well as good night vision and well-developed instrument flying skills. P-61 radar observers (R/Os) were recruited as “aerial observers,” a job description that was deliberately vague to help keep the technology secret. “It was very hush-hush,” recounted Bob Orzel, an R/O with the 422nd Night Fighter Squadron, in an interview with the New York State Military Museum. “It wasn’t until we got to basic radar ground school that we began to get some kind of inkling about what we would be doing.” In July 1942 crews began training in P-70s—radar-equipped Douglas A-20 Havocs re-purposed as interim night fighters—at the Fighter Command School, Night Fighter Division, in Orlando, Florida.

U.S. pilots in the Eighth Air Force who had served in RAF Eagle Squadrons contributed to the curriculum by recounting their experience with night interception tactics. Though most pilots arrived as second lieutenants already wearing wings, training reverted almost to square one to build skills specific to night fighting: high-and low-altitude flight in total darkness, radar-guided interception maneuvers, collaboration with ground controllers, and blind landings.

Leaving the laggard P-70s behind in Orlando, the first four U.S. night fighter squadrons arrived in England in March 1943—without their airplanes. The P-61s still weren’t operational, so crews were assigned radar-equipped two-seat British Bristol Beaufighters. Americans got instruction from the night-savvy RAF Operational Training Unit, who advised them that the Beaufighter was the most finicky of English aircraft and that, yet again, much of what they’d learned in P-70s would have to be forgotten. In an interview recorded by the Veterans History Project at Grand Valley State University in Michigan, Bob Bolinder, a U.S. pilot in the 422nd, recalled, “The Brit night fighters had already learned the trade. They had to learn it to save England.”

In the Mediterranean, the four squadrons flew nearly 5,000 night sorties in Beaufighters and were credited with 32 kills—mostly Luftwaffe Junkers Ju 88 bombers. Their experience enriched the night fighting knowledge base with practical know-how: Keep the cockpit window crystal-clean and scratch-free, turn instrument lights off completely, avoid looking at bright lights on the ground, and when firing guns, keep one eye closed to shield from muzzle flash. They also developed the habit of using onboard oxygen starting at take off, not just at altitude, which improved night vision.

Meanwhile, Northrop and company were still working on the P-61. “Jack, you’ve got a damn fine airplane!” Northrop senior test pilot Vance Breese told Jack Northrop after the first flight of XP-61 no. 1, on May 26, 1942. The original design had morphed visibly, and the prototype hadn’t yet incorporated radar. Nevertheless, the Army Air Forces ordered 670. Six long months later, XP-61 no. 2 rolled off the line.

Rethinking pre-production models consumed nearly two critical wartime years, but it turned the P-61 into a platform for innovation. The twin-tail design provided stability in the propwash behind multi-engine enemy aircraft. Spoiler-type ailerons—“spoilerons”—developed by Northrop engineers in conjunction with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, forerunner of NASA, helped the bulky twin-boomer turn as tight as a single-seat fighter. Exhaust flame dampers and flash suppressors on guns blotted out nearly all of the stray light coming from the aircraft. Strong binoculars, swing-mounted at eye level in the cockpit, incorporated an illuminated gunsight so the gunner could range-find enemy aircraft, then accurately aim a fusillade from four 20mm cannon or 50-caliber machine guns. Finally, installed in the fiberglass nose radome was the microwave radar, mass-produced on a Western Electric assembly line but still top-secret.

As the P-61 evolved, the initial engines—18-cylinder Pratt & Whitneys —were upgraded to 2,250 horsepower to enable airspeeds of 350 mph and a 33,000-foot ceiling for intercepting high-flying bombers. However, a remotely operated General Electric top gun turret—in scarce supply because priority was given to the B-29 Superfortresses—ended up being scrapped from about half the P-61s in production.

A single-seat cockpit accommodated the pilot up front; behind and above him sat the gunner, beneath a bulletproof plexiglass canopy allowing panoramic visibility. (In P-61s lacking the electric gun turret, four fixed 50-caliber guns were mounted in its place, along with four 20mm cannon underneath the aircraft’s belly, which the pilot fired. Gunners often flew missions anyway as an extra pair of eyes.) Seated backward in the aft fuselage, the R/O monitored scopes and had a clear view to the rear through a plexiglass tail cone.

In November 1943, P-61s were finally available for training. Most U.S. warplanes came from the factory in daylight camouflage: drab olive and gray. By moonlight, however, this livery was far too visible. So was flat black, oddly. Experiments showed that a high-gloss, jet-black finish gave the aircraft maximum invisibility in night skies. On the nose of one, neophyte gunner Peter Raymen painted what quickly caught on as the sobriquet for America’s first dedicated night fighter: Black Widow.

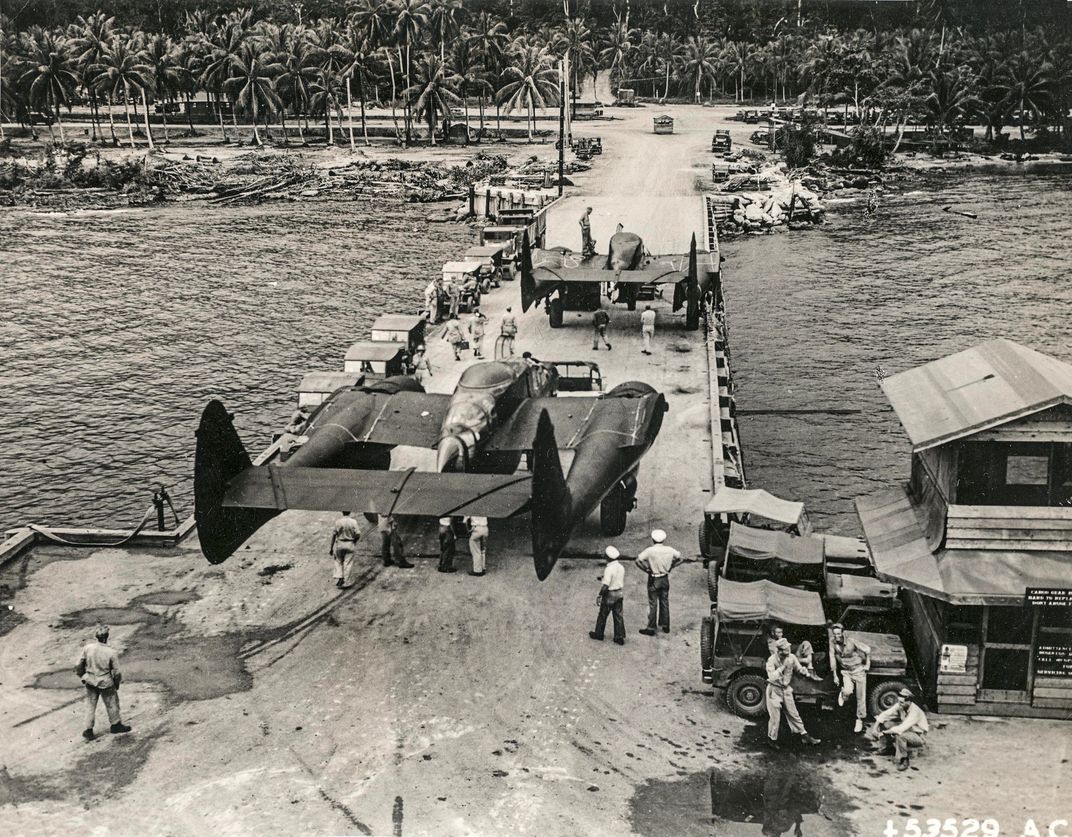

Six months later, the first combat-ready P-61s were rushed to join nightfighter squadrons in the Pacific that urgently needed an upgrade from their P-70s. Receiving the technologically advanced aircraft without training, some units struggled to assemble the Widows, which were shipped dismantled, and even fly them without instructions or pilot manuals. Northrop quickly dispatched his chief engineering test pilot, John Myers, to meet with both the brass and crews, selling them on Northrop’s unusual new product.

“Everywhere we went we were met with raised eyebrows,” Myers wrote of the response to the new aircraft. “There were remarks about it being funny-looking, awkward, odd.” Skeptical fighter jocks dared the bulky P-61 to mock dogfights. Myers, who used to test fly Lockheed P-38s, happily obliged, out-turning challengers and showing off loops, stalls, and rolls. “They were a surprised bunch before they landed,” he said. P-70 pilots in particular were quick converts. Myers recalled: “We actually had instances where crews flew her for the first time in the afternoon, then went out on successful combat missions that night.”

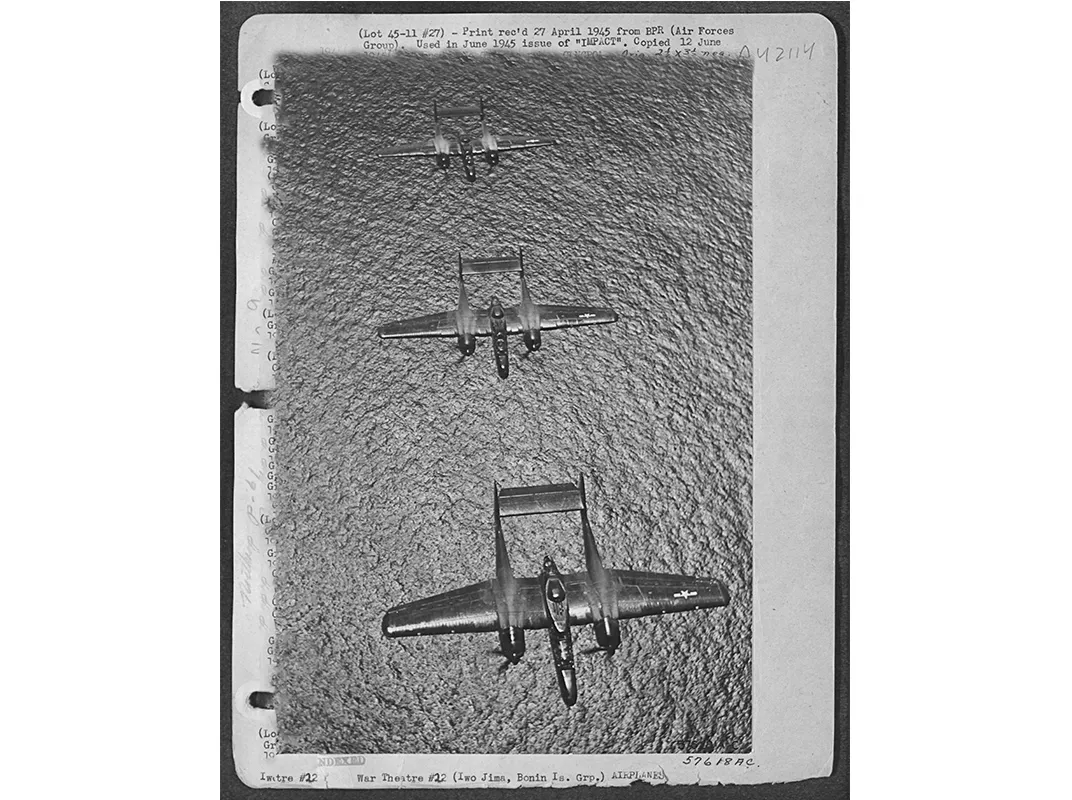

The P-61s of the Sixth Night Fighters were deployed to Saipan to provide after-hours protection for B-29 Superfortresses massing to attack mainland Japan. Nine days after arrival, the Black Widow’s long-delayed first kill was recorded.

On an initially quiet patrol in the P-61 Moonhappy, pilot Dale Haberman and his R/O Ray Mooney were notified by ground radar control of a Japanese Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber approaching head-on. Because the Betty lacked airborne radar and the Widow was virtually invisible at night, the enemy crew was unaware of the interceptor’s presence. Haberman allowed it to pass just above them, then made use of Northrop engineering’s spoilerons to pull a sharp 180, climbing to 17,000 feet and quietly taking position behind the bomber. Suddenly, the Widow’s onboard radar displayed a surprise: One blip became two. A Mitsubishi Zero escorting the Betty was tucked under one wing so close that the two airplanes had appeared to ground controllers as a single blip.

Tailgating in the darkness, a P-61 risked rear-ending its target or getting clobbered by debris produced in an up-close shootdown. Guided by Mooney’s prompts, Haberman finessed the distance as the Betty and Zero rumbled on toward the B-29 airfields, oblivious to the Widow’s proximity. When the gap between the U.S. and Japanese airplanes was just 700 feet, Mooney cleared the pilot to fire.

“I pulled the Widow up on her tail and nailed the Betty in the port engine,” Haberman recounted in Queen of the Midnight Skies. Flames erupted from the Betty’s fuselage, the nose dropped, and the bomber dived into the Pacific, exploding on impact. However, its agile escort flipped over and disappeared off Mooney’s scope.

Peering out the rear bubble, the R/O advised the pilot that the Zero was now directly behind them. Haberman threw Moonhappy into a power dive. “Mooney was looking up into the Zero’s gun barrels, telling me to twist port or starboard to make the Zero’s gunfire miss. We left him like he was in reverse.” The Japanese fighter vanished. “So we don’t know what happened,” Haberman said. “I pulled her out at 1500 feet and since nothing seemed bent or broken, we landed.”

Carroll Smith found the new sport of downing airplanes in total darkness “rather a thrilling experience if you haven’t tried it before on a good black night.” The enemy discovered that dispersing chaff, sized to jam long-wave radar, had only marginal effect on the Widow’s microwave vision. Nor could their bombers find safe haven above 30,000 feet anymore (P-70s had taken nearly 45 minutes just to reach 20,000 feet, and couldn’t breach 28,000). At the end of December 1944, the P-61s of the 418th Night Fighter Squadron took down 12 Japanese aircraft in 13 nights. In that spree, Smith alone added four shootdowns during two missions on December 29 and 30, for a total of five night victories. Near the war’s end, Japanese bombers began jettisoning bomb loads at sea and reversing course if a Black Widow infiltrated the formation.

In the Mediterranean, meanwhile, U.S. pilots were never able to bond with the British Beaufighters. “This aircraft is far below American standards,” Major Arden W. Cowgill, the commanding officer of the 414th Night Fighter Squadron, griped in a memo to higher-ups about the aircraft’s poor construction and vulnerability to wear and tear. “When the British turned airplanes over to us, naturally they didn’t give us their best ones,” said John Roberson, a crew chief in the 417th Night Fighter Squadron. The Beaus that Americans were flying were RAF hand-me-downs with airframes and engines that had significant flight hours on them. As Northrop increased P-61 production, U.S. squadrons were able to exchange the Beaufighters for shiny new Black Widows. National brand loyalty turned out to be mutual: Even though it was British interest that initiated Northrop’s night fighter program—and under the Lend-Lease Act, the Brits had dibs on 50 new P-61s—the RAF was unimpressed by a sample Widow and returned it months later. Many U.K. night fighter squadrons instead upgraded to the radar-equipped Mosquito.

The first U.S. squadron that was trained exclusively in the P-61, the 422nd, arrived in England in March 1944. One of that squadron’s pilots, Herman Ernst, flying a Widow named Borrowed Time, downed an unpiloted German V-1 “buzz bomb” over the English Channel on the night of July 15—the first Black Widow victory in the European theater.

As lone wolves stalking prey in total darkness without eyewitnesses, P-61 crews had difficulty substantiating shootdowns. Even the interceptors couldn’t always be certain they’d scored. Three probable kills of German airplanes occurred before a Black Widow crew got official credit for one. On the night of August 7, pilot Raymond Anderson and R/O John Morris were patrolling Normandy in Lovely Lady, looking to intercept a German Junkers Ju 88. Their onboard radar allowed them to get close enough to make a positive identification. With a burst of 20mm cannon fire, the Junkers exploded in a fireball. The Black Widow had taken its first verified bite of a piloted airplane in the European theater.

“We loved the dark,” said Bob Bolinder, who downed four German bombers in the P-61 Double Trouble. “We weren’t happy if it was a moonlit night.”

The European squadrons quickly established an intercept protocol. Intruders appeared on ground radar up to 150 miles away. If the distance closed to 50 miles, controllers directed a P-61 to the best guess they could make of the bogie’s path. Between 50 and 10 miles out, the Black Widow’s radar operator fine-tuned the fix, guiding the pilot directly below and behind the aircraft for identification.

U.S. rules of engagement required a positive visual I.D. before opening fire. In the night sky, an unknown aircraft’s silhouette and exhaust patterns were its main giveaways, but more striking proof sometimes appeared. Bolinder recalled sneaking up to an unidentified bogie at 10,000 feet when he saw a bold Iron Cross insignia on a Heinkel bomber suddenly loom out of the darkness. “I was shocked to see it,” he admitted, “but it was comforting to know that I really was shooting at a German airplane.” Once an unfriendly was confirmed at that minimal range, it was hard not to hit. However, if an enemy evaded the Widow and broached the 10-mile radius around a target, the night fighters backed off and let 90mm anti-aircraft batteries take their shots; allied gunners let loose at anything in their searchlights. Black Widow crews often feared them more than they feared enemy aircraft. “Under no circumstances will we hold the ack-ack,” a Pacific anti-aircraft commander warned. “This is war and a night fighter will just have to take his chances.” Close calls with friendly fire occasionally resulted in colorful radio exchanges between P-61 crews and ground gunners.

As the tide turned against Germany, Black Widows increasingly assumed the role of intruders into enemy-held territory. “If it was a slow night in the air, we would go out and shoot up targets of opportunity on the ground,” Bolinder said. The 425th Night Fighter Squadron strafed German locomotives and convoys attempting to retreat under cover of darkness from the onslaught of General Patton’s Third Army. The most productive single night shift of the war occurred on April 11, 1945, when P-61 intruders took down 14 Luftwaffe airplanes, most of them Junkers transports attempting to bring supplies to surrounded German troops.

During the Battle of the Bulge, Widows provided early proof of the all-weather fighter concept that later came to fruition in jets of the 1950s. When poor visibility grounded standard day fighters, only radar-aided P-61s were flight-ready to support ground troops—night or day.

After the war, most Black Widows overseas were ingloriously scrapped there. Crew chief John Roberson is still baffled by that decision. “It was really a top-notch airplane, that’s all I can tell you,” he says fondly today. “It was well-made and I still don’t know why they decided to obsolete it.” Out of 706 produced, just four intact examples survive, and only one, rescued from a New Guinea jungle and under restoration since 1991 at the Mid-Atlantic Air Museum in Reading, Pennsylvania, is likely to fly again.

Perhaps no P-61 crew member would have believed it on his first mission, plunging into darkness in search of a deadly rendezvous, but night work was statistically safer than flying daylight fighters. The loss rate for all night fighters was just one-half of one percent. During the war only four Widows were lost, none to direct enemy action. Of course the delay in the Widow’s combat debut skewed the number of available targets, particularly in Europe. By then, Hitler was shifting forces east, and lack of fuel was grounding many German warplanes. Bob Bolinder, who eventually flew 44 P-61 sorties and earned a Silver Star, noted, “I didn’t even see an enemy aircraft until my 30th mission.” Though four Black Widow pilots became aces, there were relatively few verified night victories: 158. On the night of August 14, 1945, after the Pacific-based crew of Lady in the Dark acquired a Nakajima Ki-43 fighter on airborne radar, Lady dogged the fighter down to water level, where it crashed into the sea near Ie Shima and exploded—one of the final aerial kills of World War II. Around noon the next day, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender.

Though late to join the war, the P-61 fought to the very end, and proved the value of airborne intercept radar, a capability that earned a permanent place in U.S. warplanes.