The Best-Built Airplane That Ever Was

The worldwide cult of the T-6.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b2/93/b293a61e-36c0-4072-bb53-b40ea07117f1/04s_dj2016_asjansmat64shipjans0406_live-web-resize.jpg)

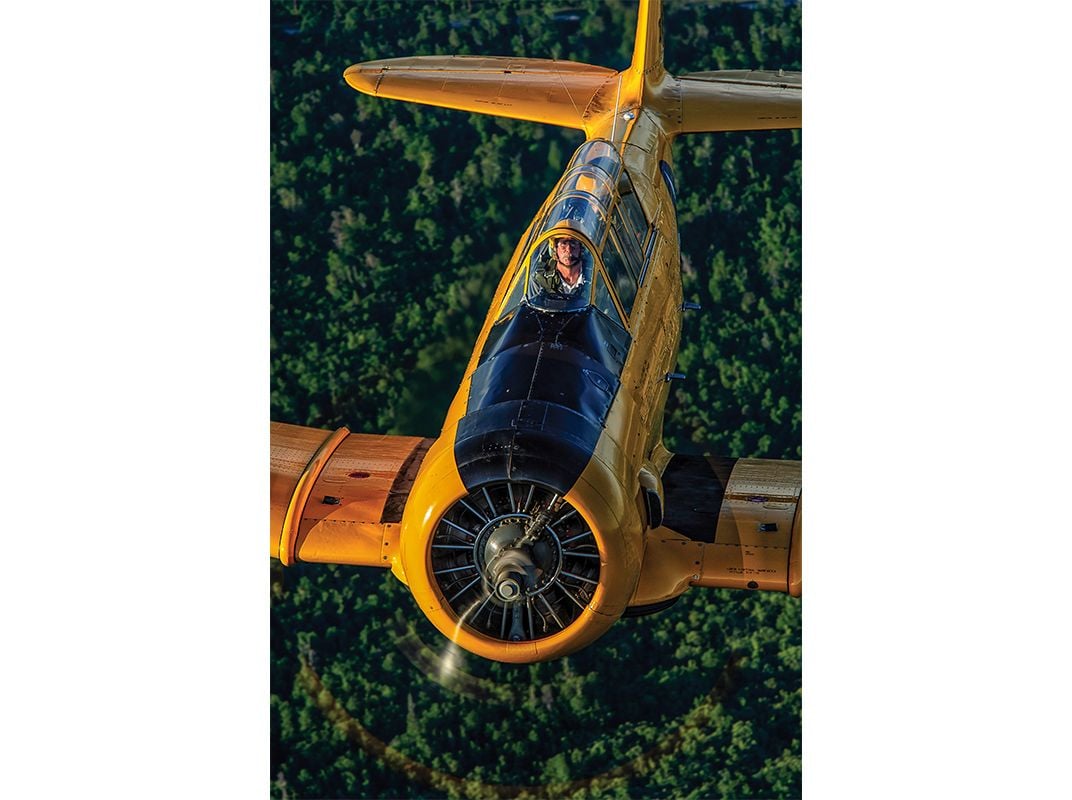

It’s that T-6 howl—that MMMRRROWWRRMmmm that deafens and pierces at the same time. “The roar of that engine is the biggest thrill in the world, as you power down the runway, coming off the ground, going through all these monkey motions to get the gear up,” says Martha Lunken, who has been flying since the early 1960s. “It’s just really fun.” But it’s more than the sound, says Mark Henley, lead pilot of the Aeroshell Aerobatic Team, which has been performing in T-6s since 2001. “We feel you gotta have plenty of noise, plenty of smoke, and be big enough to see,” he says. “And the T-6 is all three of those.”

More people hear the T-6, see it, smell it, touch it, and fly in it than any other warbird on the planet. According to the North American Trainer Association, an advocacy group for enthusiasts of the T-6, T-28, and other trainers, at least 500 T-6s (and variants, SNJs and Harvards) are flying today in the United States alone. And anyone who attends airshows can tell you that the T-6 Texan is ubiquitous. Why? Because as warbirds go, the T-6 is remarkably affordable and accessible.

Norm Goyer learned to fly in the Navy’s Aviation Cadet Training Program toward the end of World War II. He made his orientation flights at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn in the summer of 1945. When Goyer got out of the Navy, he bought two Texans from the service for $450 each. “I tell people it was the best-built airplane that ever was,” he says. “It had a North American airframe, a Hamilton Standard prop, and a Pratt & Whitney engine. Nobody made any of those things any better.” Scully Levin leads a T-6 aerobatic team in South Africa. He too loves the airplane: “The T-6 is rugged and sturdy and tough as a battleship.”

The T-6’s endurance comes down to the numbers. Like most World War II aircraft, the T-6 was built in vast quantities. A little more than 17,000 were built by North American Aviation and its overseas licensees. But what distinguished the T-6 then is what keeps it alive now: It was over-engineered, yet easy to maintain—and it didn’t become obsolete for a very long time. “There were a lot of them left over [from the war],” says Steve Larmore, a T-6 and P-51 instructor at Stallion 51 in Kissimmee, Florida. “They were still rebuilding them in the ’50s as G-models. They were built 15 percent too strong. They last a long time when they’re overbuilt in the first place.”

Fred Telling, president of the T-6 Air Racing Association, says it isn’t just that Texans were built to last—they were also built to be easy to fix. “I compare the T-6 to a 1957 Chevy,” he says. “They were the last of the cars that any person with a basic level of mechanical ability could take apart and put back together.”

Mike Ginter is living proof; to save cash on its annual inspection, he disassembles his T-6 himself. “With a Zeus tool and a screwdriver, it takes me only eight hours to take off all the panels,” he says. “Thirty or 40 panels. It helps bring the cost of the inspection down if I do all the grunt work.”

So whatever the role of a T-6 today—for pleasure flying, racing, airshows, rides, or, as ever, training—there’s support for it. But a newcomer still has to learn to fly the airplane, and that’s not easy. Besides a willingness to learn, there’s one thing a T-6 pilot needs, says Ginter: money. While modest compared to warbird fighters and bombers, this is no Cessna Skyhawk. It’s an advanced military trainer.

Family Heirloom

Taylor Stevenson, 26, says his family has never been without a T-6 since he was a baby. “The first time I flew in the T-6 I was about two or three,” the younger Stevenson recalls. He made his first solo flight in the aircraft at 22. Aeroshell team leader Mark Henley was 14 when his father bought a Texan, in 1973; flying it seemed like an ordinary thing to do. “You fly stuff that you’ve got,” Henley says. “We just happened to have a T-6.”

Sometimes the decision to buy one can be almost impulsive. Gordon Stevenson, Taylor’s dad, bought his after seeing one at an airshow—but before he’d had any flight training. Fred Telling jumped into T-6 racing after watching the trainers compete at the Reno air races. “I thought, ‘I could do that, that’d be fun!’ My wife looked at me like ‘Who are you kidding?’ ” he recalls, laughing. “I didn’t know anything about T-6s other than watching them and seeing them in the pits.”

But most budding T-6 pilots arrive at their choice of aircraft more carefully. No doubt aware of its reputation as “The Pilot Maker,” the pilots who seek out T-6s also know that the minimum requirements for a T-6 owner-operator can still be daunting.

“I call it a 5,000-pound tail-dragger with a mean streak,” says Steve Larmore, who has logged 4,600 hours in the airplane, most as an instructor. “It’s a delight to fly in the air, but it’ll ground-loop in a heartbeat.” Norm Goyer puts it in colorful terms. “When you get 5,980 pounds that wants to turn sideways, a tap on the rudder pedal ain’t gonna correct it,” he says. “Two 500-pound guys standing on it might.” Larmore has a prerequisite for pilots with little tail-dragger experience: “I tell them to go out and get a bunch of landings, preferably in a Pitts. But anything will do—a Super Cub, a Citabria, anything where you have to work to keep it straight and bring that to the table when you come to fly the T-6.” (World War II pilots in training generally worked their way up to the T-6 via the Piper Cub or an Aeronca or a Vultee Valiant.)

Flying Texans can be an expensive habit. Today, the baseline price of an airworthy T-6 is about $150,000 to $250,000 or more. “Every year, there’s two, three, four thousand bucks that goes into that airplane, in addition to the mortgage, the hangar, the insurance, and then the gas,” says Ginter. “The gas is roughly six bucks a gallon, and the T-6 burns 30 gallons an hour. So in addition to the fixed costs of ownership and maintenance, it’s $180 an hour to fly it. Factoring in everything—oil, parachute packing every 180 days, subscription to aeronautical charts—the operating cost is about $500 an hour.”

For the person of average means and time, probably the most affordable route to the T-6 is joining a Commemorative Air Force squadron. Many squadrons around the country have at least one T-6, and CAF membership allows regular proximity to an airplane and a hand in its care. For many, that’s enough to scratch the itch.

But not for all. Rob Krieg is a Marine veteran who, with his wife Amy, joined a CAF squadron in Virginia to help deal with his “drastic aviation sickness,” as he calls it. Krieg used the squadron’s airplanes to build up tail-dragger time. “I’m like a typical air cadet from back in the ’40s,” he says. “I learned in a primary trainer, then went to the BT-13, and now I’ve stepped up into a T-6.” Early in 2015, he split the price of a T-6 with two partners, one of whom is still learning to fly. Krieg is philosophical about the cost. “Warbirds are expensive,” he says, “but so is golf. I tell my golfing friends that it’s the same price—but they take all day to do it, and I’m done in an hour.”

Self-Governance

T-6 enthusiasts are organized—thanks in part to the large warbird fan clubs, like the Commemorative Air Force and the Experimental Aircraft Association’s Warbirds of America. But the groups largely or fully devoted to the T-6, the North American Trainer Association and the T-6 Racing Association, have the best-established training programs in formation flying and racing, not only for T-6 pilots but for the broader warbird community. Each program coalesced around the need for safety and standards—T-6 formations were getting larger, and an increase in the number of pilots who’d had no formation training was worrisome.

NATA began teaching its Formation and Safety Team curriculum in 1987. Earning a FAST card allows T-6 pilots to fly in formations, which can often grow to 20 aircraft and on rare occasions several times that. Taylor Stevenson may be NATA’s youngest member, but he typifies the participation in the program. “It’s kind of a ‘Pay it forward’ thing,” he says. “Everyone goes to [formation clinics] and spends their own money on gas so the next guy can get certified. We want people checked out.”

The same impulse guided Telling to help develop a curriculum for T-6 racers. “For a long time, the warbirds people didn’t consider the T-6 worthy,” he says. Bearcats and Mustangs just seemed to be in a different class from the T-6. “It wasn’t until 1968 that the T-6s started to race at Reno.” They’ve raced there every year since 1981.

“In the early years, people would just show up to race, and they might not have raced around pylons or had any formation flying experience,” Telling continues, noting that many of the pilots then were cropdusters and ex-military pilots who could adapt to racing quickly. In the late 1990s, the Reno Air Racing Association began its pylon racing school. Telling calls it a huge advancement in safety. Now, the T-6 Racing Association also requires a FAST card. “It weeds out the uninitiated,” Telling says, “and then pylon racing school teaches you the rest.”

But the T-6 Racing Association began developing its own approach to racing training—including ground school, pattern flying, and a host of particulars for racing at the Reno Air Races. The program grew from hand-drawn diagrams to detailed, animated video presentations. After Jimmy Leeward’s fatal P-51D crash in 2011—which also killed 10 spectators—Telling says their curriculum became the Federal Aviation Administration-approved basis for training in the other racing classes. It’s for rookies and veterans alike.

“It’s been wonderful,” says Telling. “It’s provided us with a level of competence and consistency that everyone can train to. We’re very proud of that.”

When the T-6 Is Your Job

T-6s aren’t just for recreation. For Aeroshell’s lead pilot, Mark Henley, the aircraft’s many pluses come together to make the T-6 a perfect and—with strong sponsorship—profitable performer. “For the most part, your airshow revenue is covering your expenses,” he says. “There’s no way you’d ever earn enough to make a living flying a Mustang. The cost of operation is just too high.”

Larry Arken, the lead pilot for the GEICO Skytypers, has his T-6s on double duty as part of an airshow team and as actual skywriting instruments, executing enormous messages in vapor for everyone from Starbucks to bridegrooms-to-be. (There’s nothing like a eight-mile-wide proposal.) “The airplane is great in formations,” says Arken, “and it’s got the carrying capacity for the smoke oil we use for the skytyping missions. So is there a better airplane to fit both the airshow world and the skytyping world—and economically? The answer is no.”

The T-6’s two cockpits make it ideal for giving rides. The website warbirdalley.com lists (as of October 2015) more than two dozen operations offering T-6 rides. Larmore, an early practitioner of the business, says: “We barnstormed three T-6s with more than one company in 10 or so markets. So we were all over the country doing 10 rides a day, 14 rides a day.”

All those rides add up to a lot of time on vintage airframes, the airplane’s least replaceable part. But Henley puts its durability in perspective. “My airframe has 7,000 hours on it,” he says. “In the scheme of things, that’s not a ton of time. Some of the ride operators using T-6s have 14 or 15,000 hours from hopping rides every day, and those airplanes are still rockin’.”

Planet T-6

There are Texans or SNJs or Harvards or Yales (early T-6s intended for France that ended up in Canada) flying on almost every continent and in dozens of countries: the Canadian Harvard Aircraft Association, the Oi demonstration team in Brazil, the New Zealand Red Checkers and Roaring Forties teams, and the United Kingdom’s T-6 Harvard Aviation all offer rides, demos, and filming.

But no country has been as critical to the current state of the T-6 as South Africa.

“This year [2015], we celebrate 75 years of the Harvard in South African skies,” says Scully Levin, who after leaving the South African air force flew big passenger jetliners for South African Airways for 38 years. “From 1940 to 1995 they were our primary trainer,” he says, adding that in 1995, the air force had more than 120.

For training capabilities, Levin appreciates the T-6 as deeply as he does his American counterparts, but he also acknowledges the unique reality South Africa experienced until 1994: “They faced sanctions because of the apartheid policy, and they weren’t able to find other airplanes easily. They had this huge number of Harvards, which were doing a fantastic job, so they kept them.”

When the airplane was finally decommissioned, in 1995, Morey Darznieks, the proprietor of Lance Aircraft, was there as the spares were auctioned off, and he shipped them all back to Dallas (see “T-6 World,” p. 26). “That fellow bought up virtually everything South Africa had,” says Levin. The country’s loss was the rest of the T-6 world’s gain. T-6 pilots of every stripe credit the spares from South Africa as a great resource for the airplane’s present and future. But back home, Levin says, “it’s very sad that these things actually left South Africa and we have to buy the parts back. And our currency has also gone to hell. That’s just the way the cookie crumbles.”

Still, there are active Harvard Clubs in South Africa, and Levin estimates about 35 T-6s remain in the country. Levin himself still is able to enjoy the airplane and, like his American counterparts, to do so as a business. He’s the lead pilot for the Eqstra Flying Lions, a formation aerobatic team. “Wherever we go, we steal the show with our four Harvards,” he says. “The audience loves the sound, the airplane has attitude, it looks good, and we’re able to make our displays very tight.” His team perfected the water-skiing Harvard maneuver, in which the formation descends, gear down, to a lake and rolls the wheels on the water.

Harvard v. iPad

Like all warbirds, the T-6’s future depends on its ability to catch the attention of younger folk. Taylor Stevenson realizes that, as a millennial T-6 pilot, he is rare. He has a couple of friends, also in their 20s, who grew up with the airplanes and fly with him. “It’s fun and it’s scary,” he says. “It’s fun ’cause there’s guys your age flying these really cool airplanes, they appreciate the history. But it’s scary ’cause there’s so few of us.”

Larmore defines “young” differently. “The next generation isn’t as connected [to World War II], especially if they don’t have family who were in the war. But for the 40-, 50-, 60-year-olds, it’s going strong. I don’t see any change in the next 10 to 20 years. A lot of guys retiring from the military in their late 40s or early 50s find their way to the T-6. There’s still a lot of sentiment there.”

Through his business, Courtesy Aircraft in Rockford, Illinois, Mark Clark sells Texans and other warbirds. Now in his early 60s, Clark says: “The majority of my T-6 customers are younger than I am. It’s not like I get 70-year-old guys coming to buy T-6s. I’ve had customers in their 40s, mid-30s, and have friends in their early 20s who fly them.” Clark says the number of owners who show an interest in the T-6’s history as well as its utility is growing. “In the mid-’70s, people just wanted to fly a surplus airplane, and they’d paint it white with a blue stripe down the side,” he says. “But slowly it’s transitioned to the exquisite, ground-up, historically very authentic restorations that are being done today.”

New owners like CAF member Rob Krieg take that stewardship seriously. “We’re just the caretaker,” he says. “Hopefully this airplane will outlast me, and someone else will take care of it.”

That sense of legacy is important, because even the biggest fans acknowledge that the T-6’s preeminence as a trainer for contemporary aircraft is long over. “Aviation has moved on,” says Levin. “Today, if you’re any good with your Apple iPad, you’re going to make a good pilot, I guess. Being of the old school, I would say there’s not a way in hell that [the newer South African air force Pilatus trainers] turn out a better pilot than the Harvards did.”

Bill Fischer, executive director of EAA’s Warbirds of America, sees increasing participation among younger pilots as an ongoing challenge. “But 97 percent of our attendees at AirVenture [the annual EAA gathering at Oshkosh] come to the warbirds area,” he says. And the T-6 is the biggest piece of the pie. “Every year we have 50 to 75 T-6s.”

As with all things T-6, it comes down to the numbers. May they stay high.

T-6 World

![04ZD_DJ2016_010[6]_LIVE.jpg](https://th-thumbnailer.cdn-si-edu.com/5QNkF5JFKHvPfQJ3X-FIgvpkll8=/fit-in/1072x0/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9f/d1/9fd15a57-bf0b-4f8a-b9c7-6c6d23d24b75/04zd_dj2016_0106_live.jpg)

The center of the T-6 world is a 70,000-square-foot warehouse in Dallas that houses Lance Aircraft Supply. Everyone who owns a T-6 relies on this family-run company.

“We own about 95 percent of the spares that are left for the airplane,” says John Darznieks, who runs the business with his parents and sister. “Out of that, about 90 percent is new surplus—never been put on an airframe.”

The Darzniekses cannot foresee ever running out. “Our customers—with their 70-year-old airplanes—can get parts faster than people that have Cessnas, Gulfstreams, and things like that,” John Darznieks says. “They can have their parts the next day, so long as they don’t call me too late in the afternoon.”

How did such a bounty come to be concentrated in one place?

“I had to eat,” says Morey Darznieks, John’s father. Born in Latvia, the elder Darznieks has lived a life of reinvention.

His family immigrated to Columbiana, Ohio, when he was a child. As a young man, he sought his fortune in California, becoming a mechanic, and later a salesman, for an aircraft parts supplier. The smog of the San Fernando Valley was too much for his asthmatic son, so he accepted an invitation to work for another aircraft parts company in Dallas. But by the time he and his family arrived from California, the company had gone out of business. He founded Lance Aircraft supply in his carport. Incorporated in 1967, the company grew from the carport to a second house to a warehouse. When the warehouse burned down in the mid-1970s, Darznieks started again.

He began traveling the world, hunting for T-6 engines and props to support cropdusting operations in the United States. (Farmers love the Texan’s reliability.) He brought home airframes too. He made one of his biggest scores in India, whose air force had phased out the Texan and the Harvard in the 1970s.

Darznieks stayed in the engine business until 1983, when the Reagan administration implemented a subsidies program that had a disastrous effect on farming. “The cropdusting industry died,” Darznieks says. “We went from four [engine sales] a month to zero.” Another restart needed.

The entire family pitched in to inventory their airframe parts, then began selling them. That family business became an empire. In 1983 or 1984, Darznieks acquired the company North American had licensed to manufacture T-6 parts. In 1986, he bought his chief competitor, Chesapeake Airways, in part, he says, to protect the T-6 supply chain from “a group of lawyers from Philly who wanted to buy me up too, jack up the price, and sell only to rich people.” He appreciates the work T-6 enthusiasts do to preserve the aircraft’s history and legacy; he wasn’t interested in seeing a big chunk of them priced out.

Asked if he’ll accept only a certain profit margin, the elder Darznieks explains that he sets prices according to “the WAG system. I’m sure you’re familiar with that.”

We are not familiar with that.

“You look at a part and you take a Wild Ass Guess what it’s worth,” he says. “We figure out what it would cost to make it, and try to stay below that.”

He’s been to 45 countries to buy up their air force inventory. When he bought the South African air force’s supply in 1998, he ensured that Lance Aircraft would remain the chief T-6 supplier. But could he fly one? “Oh no,” he laughs. “I ain’t smart enough to be a pilot.”