The Biggest Industrial Boom in U.S. History

How Roosevelt’s fireside chat changed American culture.

:focal(1500x665:1501x666)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/f3/46f308ff-ead3-4cb7-8a0a-96d97d390ae2/01j_am2015_enginespwr2800_live-cr.jpg)

When Americans tuned their radios to hear President Franklin Roosevelt deliver an informal address in December 1940, war seemed distant. “The people of Europe who are defending themselves do not ask us to do their fighting,” Roosevelt assured his listeners. “They ask us for the implements of war, the planes, the tanks, the guns, the freighters which will enable them to fight for their liberty and for our security…. We must be the great arsenal of democracy…. We must apply ourselves to our task with the same resolution, the same sense of urgency, the same spirit of patriotism and sacrifice as we would show were we at war.”

A year later the United States was at war, and its aircraft production had doubled. The following year, it doubled again, and by 1945 the country had produced 304,000 aircraft, more than Germany and Japan combined.

More Floor Space

To mobilize for war, the Roosevelt administration created the Defense Plant Corporation to oversee the construction of government-owned munitions factories, which were then leased to manufacturers. One of its largest projects was the 6.3-million-square-foot Dodge-Chicago plant, built in 1942 on Chicago’s south side to make B-29 engines. Raw steel and aluminum entered at one end and Wright R-3350 Duplex Cyclones emerged from the other, 18,000 times. In 1965, the plant became the Ford-City shopping mall. Today, part of the complex houses a Tootsie Roll factory, with a visitors’ gallery that displays a B-29 engine.

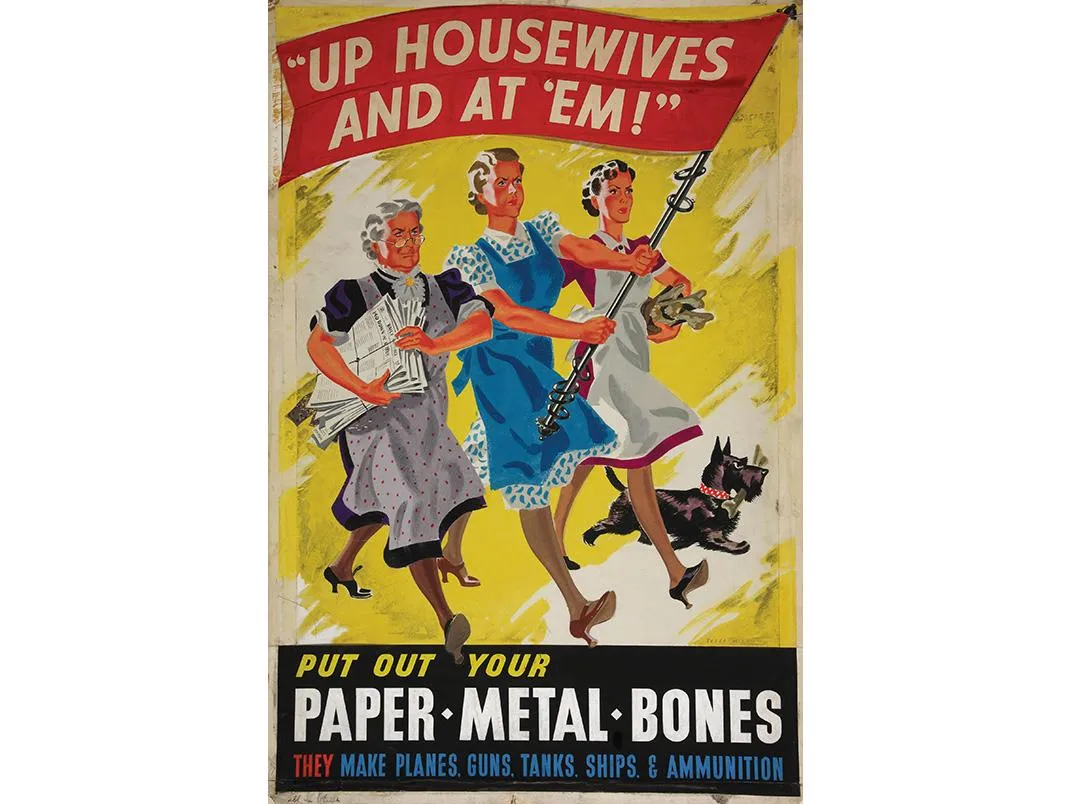

Made From Scrap

Airplanes weren’t. Scrap drives collected more than six million pounds of aluminum pots and pans and other kitchen utensils, but many were recycled into…pots and pans. Airplanes were made from higher-grade aluminum, and the vast supply needed came from building new refineries, boosting production at existing suppliers, and mining more bauxite, the mineral from which aluminum is made.

When silk could no longer be obtained from Japan, the War Production Board launched a drive for silk and nylon stockings, and within four months collected 880,000 pounds, which could be converted into parachutes and glider tow rope, but was a tiny fraction of what was needed. Economists have shown that World War II scrap drives had almost no impact on output, but historians say they promoted patriotism.

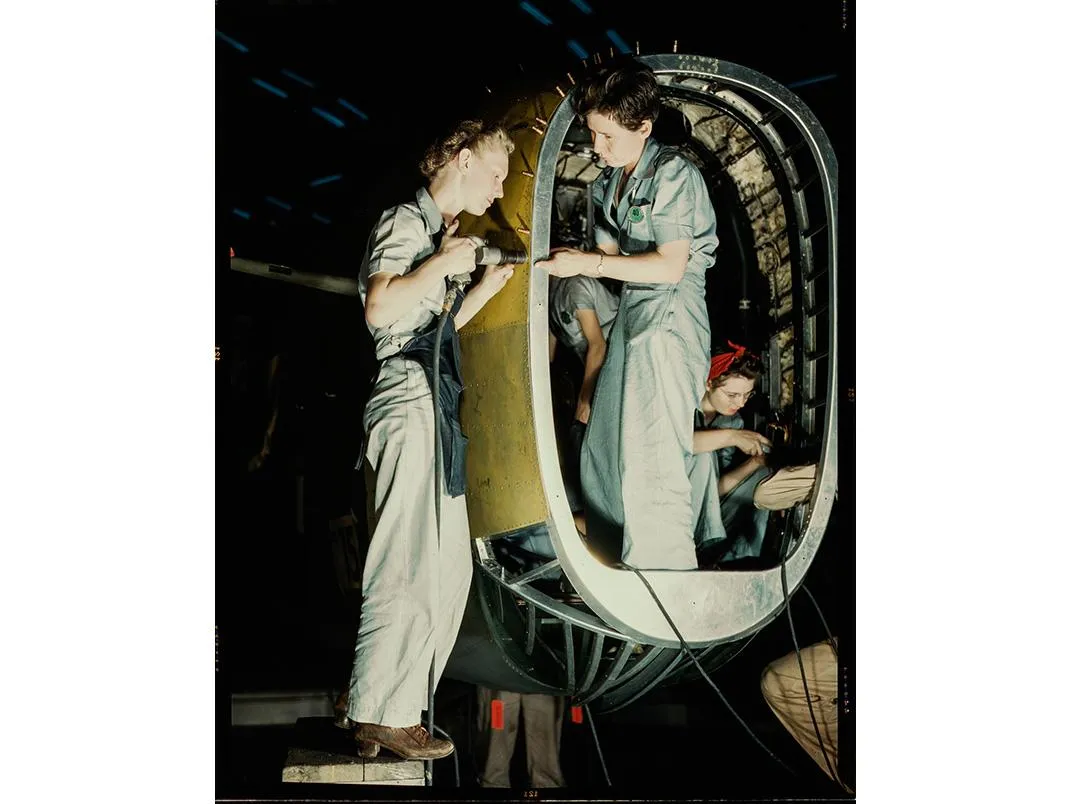

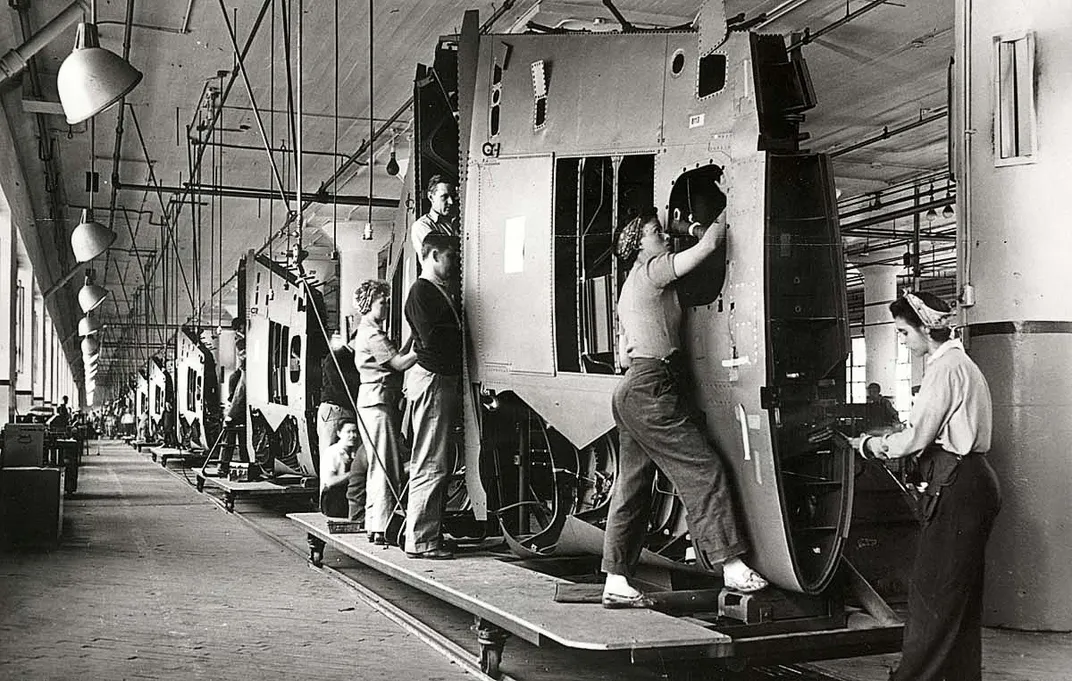

The Workforce

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, U.S. aircraft and engine plants ran 24 hours a day and required new workers to keep them going. Many were women. Before the war, women constituted only a quarter of the U.S. workforce. Most of them were single and held positions mainly in service, hospitality, and retail. By 1945, 19.1 million women held 36 percent of jobs, and many were married because a large number of servicemen wed before deployment. As women left the domestic and service jobs they had held before the war, minorities filled in. After a protest by the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Roosevelt signed an executive order banning discrimination in U.S. defense plants, and a half-million African Americans migrated north and west to fill jobs in aircraft and munitions factories.

Riveting Statistics

Several hundred thousand rivets are needed to fasten together the pieces of a single bomber. The Ford plant at Willow Run, Michigan, made seven million rivets a day. Produced in more than 500 standard sizes, rivets were first sorted in what must have been the dullest job at the plant. They were then driven by a pair of workers. The riveter would drive, and her force was opposed by the bucker, who applied a bucking bar. Because riveters had to fit in the cramped compartments of airplane interiors, workers were sometimes selected for their small size.

One riveter, Rose Will Monroe, was plucked from a B-24 assembly line to appear in Hollywood promotional films, and another, Rose Bonavita, set a record by driving 3,300 rivets into a Grumman TBM Avenger during one six-hour shift. But the images of Rosie the Riveter—the Norman Rockwell cover of a 1943 issue of the Saturday Evening Post, the description in a popular 1942 song, or the iconic poster widely used after the war to represent the women who built airplanes during the 1940s—are composites of many women.

Powerhouse

When war broke out, only three U.S. companies built military aircraft engines. Eventually, the original trio—Wright Aeronautical in Paterson, New Jersey, the Pratt & Whitney division of United Aircraft in Hartford, Connecticut, and the Allison Division of General Motors in Indianapolis—partnered with Buick, Chevrolet, Dodge, Ford, Packard, Studebaker, and others to crank out 808,000 engines and 799,000 propellers for the Army Air Forces. By 1945 engine manufacturers delivered a 10-fold growth in yearly output.

Efficiency Saves

As the machines and methods of aircraft construction improved, the unit cost of each airplane fell. The Republic P-47 cost the Army Air Forces $113,246 in 1939; it could be had for $85,578 in 1944. Curtiss P-40s cost $77,159 in 1939, and only $50,466 in 1944. A Boeing B-17 sold for $301,221 in 1939, but for only $187,742 in 1945.

Mix and Match

When a manufacturer’s capacity to produce a type of aircraft fell short of the demand, the military services and government-formed committees prevailed on companies to license their designs for construction by others. The Eastern Aircraft division of General Motors built more than 5,000 of the 7,860 Grumman-designed Wildcats produced. (GM’s were designated FM-1 or -2, instead of F4F.) Eastern also built most of the Navy’s Avenger torpedo bombers. At a Nashville plant, Consolidated built 133 Lockheed-designed P-38 Lightnings. Bell Aircraft constructed 652 Boeing B-29s in Marietta, Georgia, and Consolidated, Douglas, Ford, and North American all built B-24s.

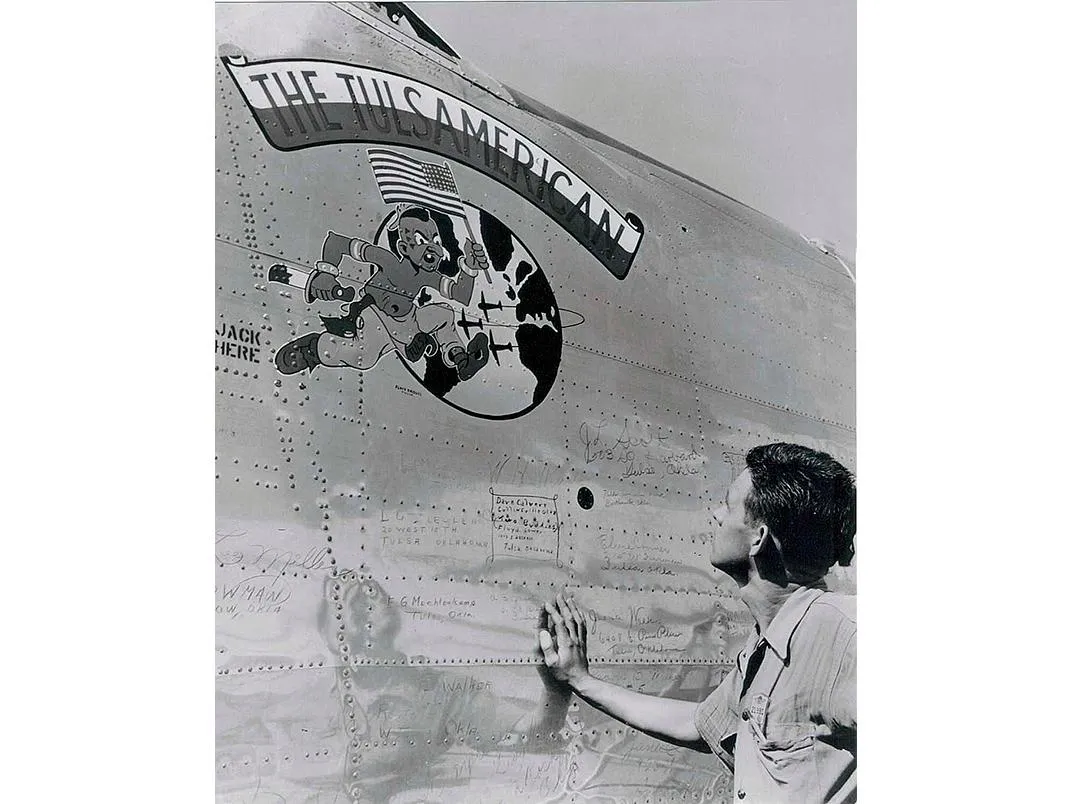

B-24s, First to Last

More B-24 Liberators—18,482—were built than any other U.S. warplane, and by 1944 a complete airplane left the Ford-managed Willow Run factory every hour. At a Douglas Aircraft plant in Tulsa, Oklahoma, B-24s were assembled from Willow Run-produced parts. The last assembled there, the Tulsamerican, was paid for by the workers, through their purchase of war bonds. On its final mission, on December 17, 1944, the Tulsamerican took German fire and fell into the Adriatic Sea off Croatia, killing three of its 10 crewmen. In 2010, wreckage of the Tulsamerican was found, its serial plate brought to the surface, and the last living survivor, 92-year-old Val Miller of Oklahoma City, interviewed for a local paper.