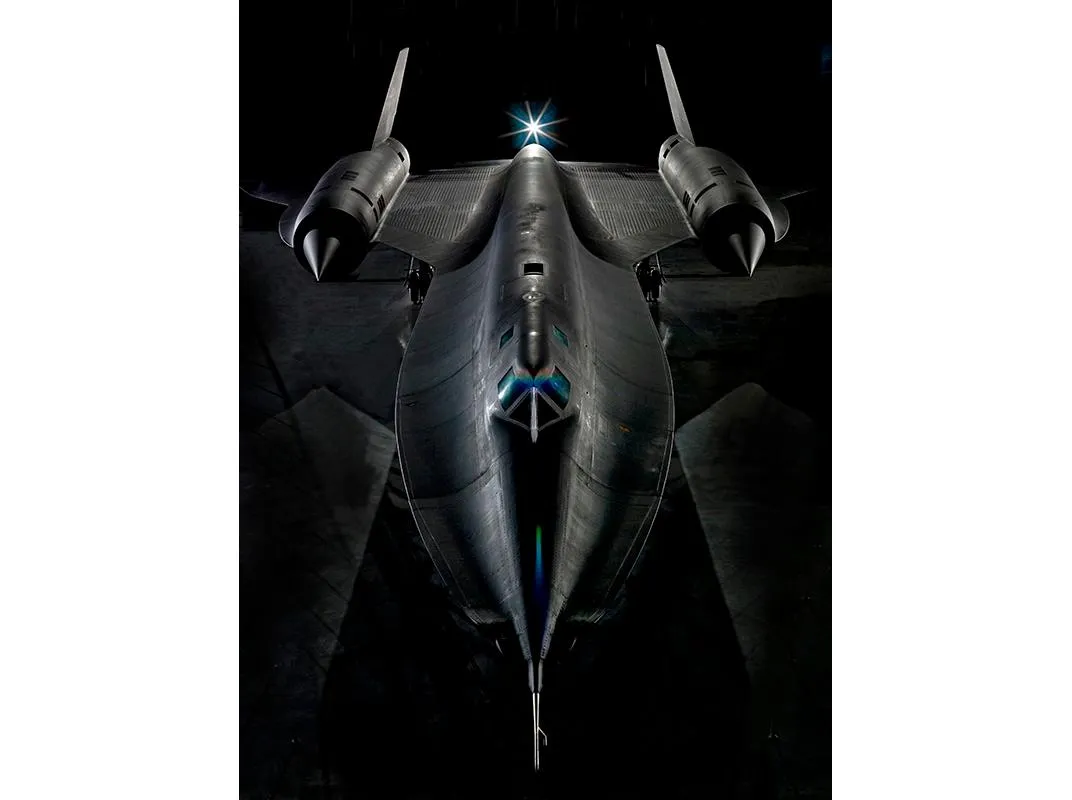

Blackbird Diaries

Stories from the fastest jet ever flown.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/fc/8efcd90d-be3b-4f7c-b5d9-0383ba3f089c/blackbird_opener.jpg)

When Bob Gilliland made the first flight of the SR-71 on December 22, 1964, engineers were still tweaking 379 items on the aircraft. That didn’t deter Gilliland, who took the airplane to 50,000 feet and Mach 1.5. At a 2010 talk in Ridgecrest, California, Gilliland recounted that he ignored the one error message he saw in the cockpit that day: “Canopy Unsafe.”

We have the cold war, Kelly Johnson, and the CIA to thank for what is still the fastest aircraft propelled by jet engines. Once the U-2 proved vulnerable to the Soviet Union’s surface-to-air missiles, the CIA issued a contract for a spyplane that could evade SAMs. Johnson responded with the A-12, the aircraft that would evolve into the SR-71.

Fifty years later, the Blackbird continues to mesmerize pilots and public alike. During its career, the reconnaissance aircraft gathered intelligence all over the globe. Crews spied on military activities in North Vietnam, took imagery during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, flew over the Persian Gulf, and peered into the former Soviet Union.

We’ve collected just a few of the stories from Blackbird crews, but when we asked pilots to compare it to other aircraft they’d flown, we stumped them. One summed up the slim similarities: “It’s got controls and a throttle.” Visit airspacemag.com for additional stories, pictures, and trivia—and add your own. —The Editors

Some stories first appeared in Richard Graham’s SR-71 Blackbird: Stories, Tales, and Legends; and SR-71 Revealed: The Inside Story. Excerpts are used with permission.

Colonel James H. Shelton Jr.

Shelton was the first Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron commander of the SR-71 unit at Beale Air Force Base, California. He was the fifth SR-71 crew member to reach the 900-flying-hour plateau.

During the October 1973 Yom Kippur War, our government wanted to know the battlefield situation between the Israelis and Egyptians. They couldn’t move one of our spy satellites out of a Russian orbit due to higher-priority targeting. Lieutenant Colonel Gary Coleman (recon systems officer) and I were asked to obtain the information. We were to take off from Beale Air Force Base, fly through the Mediterranean Sea, down the Suez Canal, around the city of Cairo, Egypt, head through Israel, back through the Mediterranean, and recover at RAF Mildenhall, England. This would be about an 8-hour-and-45-minute flight.

The next day, we were informed that the British would not let the SR-71 land in England due to their dependence on Middle East oil. The new plan was to fly from Griffiss Air Force Base, New York, through the Middle East and return to Griffiss. It meant that the mission was now 11 hours and 30 minutes.

As we headed down the Suez Canal, Gary informed me that a SAM site in Egypt was tracking us. We maintained speed and heading. Fortunately, as we continued south over the Suez Canal, the SAM site stopped tracking our plane. Eventually, we turned west to circle around Cairo. Once again, an Egyptian SAM site started tracking us. Through the side window, I spotted high-altitude condensation trails approximately 40,000 feet below us. Now we had fighter aircraft trying to track us or attempting to shoot us down, as well as the threat from the SAM site. Based on our location, I believed they were Egyptian aircraft and not Israelis.

Our sixth air refueling was over Canada. Knowing the weather at Griffiss was clear and we wouldn’t need any extra fuel, I pushed the throttles up to full military power, just before the afterburner range. This increased our speed to around Mach .98. The Canadian air traffic controller kept asking us what type of aircraft we were. I responded, “As filed on our flight plan.” After landing, I questioned our mission planners as to the type of aircraft they had indicated on our flight plan. They replied, “A KC-135 tanker.” No wonder the traffic controller wanted to know the type of aircraft—a KC-135 flies almost 150 miles per hour slower than I was going.

Our photos showed that the Israelis had moved farther into Egypt than Golda Meir had admitted. The State Department used these photos to convince Meir to withdraw from Egyptian territory.

Major Jerry Crew

Crew was a navigator on B-47s and B-52Gs when he became aware of the SR-71 program. After 308 hours in the back seat of the SR-71 and an unplanned medical retirement, Crew is now known as the World’s Fastest Farmer.The morning of 26 July 1968 started as another typical day at our detachment on Okinawa. Major Tony Bevacqua, pilot, and I formed Crew 013. We were hoping for a chance to fly an operational sortie over North Vietnam and, because of a glitch with the crew in line ahead of us, got it.

Our mission would take us over Hanoi and Haiphong. North Vietnam had been socked in for two weeks by weather. Knowing that current, up-to-the-minute intelligence was necessary to conduct the ground war added urgency to our mission.

Turning inbound on our first sensor run, I noticed the “R” light on my electronic countermeasures (ECM) panel was illuminated. A North Vietnamese SAM site was tracking us on its radar.

What we didn’t expect was the illumination of the “M” light, followed closely by the “L” light! This meant that the North Vietnamese had actually fired one or more SAMs at us. (The “R” light meant they were searching for you, the “M” light meant they were tracking you, and the “L” light meant they were launching at you.) Attempting to seem calm (I failed), I told Tony we had just had a SAM shot at us.

This news couldn’t have occurred at a worse time. We had just started our sensor take, and evasive action was not an option. Tony asked how long ago was it launched, and I replied, “About five seconds.” The time of missile launch was important; we were told countless times by our intelligence experts that the SA-2 missile’s total flight time was only 58 seconds. In other words, if nothing happened by then, we were probably safe.

We had practiced what to do in the event of a SAM launch many times in the simulator. My duty was to turn off the ECM jammer because we didn’t want the missile tracking the jamming frequency during flight. The purpose of our jammer was to confuse the missile prior to launch. My other duty was to start the stopwatch to time the missile’s flight.

My reaction time seemed terribly slow. It took forever to turn off the jammer (actual time: five seconds), and I never started the stopwatch. However, I did notice the position of the second hand on the clock when Tony asked how long ago the missile had been fired.

The next 50 seconds are in dispute! I thought the whole time was spent answering Tony about the length of the missile’s flight. “How long has it been?” he asked. “Five seconds since the last time you asked,” I answered. Interphone tapes show that Tony only asked four times. I do know it took much longer than the missile’s predicted flight time to convince us of our safety.

We completed the sensor run and descended to our tanker over Thailand, preparing for our return run back over North Vietnam.

In reality, two missiles had been fired at us. Luckily they shot early and below us—our cameras confirmed this.

Major Reg Blackwell

Blackwell had about 3,500 hours as an RC-135 navigator before entering the SR-71 program. He left the program in 1976 to attend Air Command and Staff College.Pilot Colonel Darryl Cobb and I experienced two separate flameouts while on deployment to Okinawa. During the first flameout, we were getting ready to fly down to Vietnam to take some bomb assessment pictures. After we’d taken on fuel, the inlet guide vein failed to shift. As we were descending, heading back to Kadena Air Base, I said to Darryl at 55,000 feet, “Can you get the engines restarted?” His response was “How did you know they’re out?” I said, “My suit started to inflate.”

At 10,000 feet, if it’s obvious the plane is going to crash, the RSO is supposed to eject. So we’re at about 20,000 feet, and I started reading the emergency checklist sewn on the pressure suit arm, on how to get into a rubber raft without puncturing it.

At 12,500 feet, Darryl got one engine started, and the other came on at about 11,000 feet. This happened on my first operational sortie.

On another mission, we were descending into Thailand to take on fuel from a tanker at 25,000 feet when Darryl saw a thunderstorm topped at 62,000 feet. He decided to take the SR off auto-navigation, and once we got to the other side of the thunderstorm, we’d do an emergency descent to get back on the profile.

As soon as we started down, both engines flamed out. We got the first engine started at 26,000 feet, and the second at about 22,500.

We’re probably the only pilot and RSO who have about 20 or 30 minutes of triple-sonic glider time.

Major Brian Shul

Shul was the first pilot to write a book about flying the SR-71. This story comes from his book Sled Driver: Flying the World’s Fastest Jet, first published in 1991, now in its sixth printing.Walter and I had just completed the 100 hours required to attain Mission Ready status in the jet. Ripping across the Arizona deserts 80,000 feet below us, I could already see the coast of California.

I was beginning to feel a bit sorry for Walter in the back seat. There he was, with no really good view of the incredible sights before us, tasked with monitoring four different radios. The predominant radio chatter was from Los Angeles Center, controlling daily traffic in their sector. While they had us on their scope (albeit briefly), we were in uncontrolled airspace and normally would not talk to them unless we needed to descend into their airspace.

We listened as the shaky voice of a lone Cessna pilot asked Center for a readout of his ground speed. Center replied: “November Charlie 175, I’m showing you at 90 knots on the ground.”

Now the thing to understand about Center controllers was that whether they were talking to a rookie pilot in a Cessna or to Air Force One, they always spoke in the exact same, calm, deep, professional, tone that made one feel important. I referred to it as the “Houston Center voice.” Conversely, over the years, pilots always wanted to ensure that, when transmitting, they sounded like Chuck Yeager, or at least like John Wayne. Better to die than sound bad on the radios.

Just moments after the Cessna’s inquiry, a Twin Beech piped up on frequency, in a rather superior tone, asking for his ground speed. “I have you at 125 knots of ground speed.” Boy, I thought, the Beechcraft really must think he is dazzling his Cessna brethren. Then out of the blue, a Navy F/A-18 pilot out of Naval Air Station Lemoore came up on frequency. You knew right away it was a Navy jock because he sounded very cool on the radios. “Center, Dusty 52 ground speed check.” Before Center could reply, I’m thinking to myself, “Hey, Dusty 52 has a ground speed indicator in that million-dollar cockpit, so why is he asking Center for a readout?” Then I got it. Ol’ Dusty here is making sure that every bug smasher from Mount Whitney to the Mojave knows what true speed is. He’s the fastest dude in the valley today, and he just wants everyone to know how much fun he is having in his new Hornet. And the reply, always with that same calm voice, with more distinct alliteration than emotion: “Dusty 52, Center, we have you at 620 on the ground.”

And I thought to myself: Is this a ripe situation, or what? As my hand instinctively reached for the mic button, I had to remind myself that Walt was in control of the radios. Still, I thought, it must be done. That Hornet must die, and die now.

Then I heard it. The click of the mic button from the back seat. That was the very moment that I knew Walter and I had become a crew. Very professionally, Walter spoke: “Los Angeles Center, Aspen 20, can you give us a ground speed check?” There was no hesitation: “Aspen 20, I show you at 1,842 knots, across the ground.”

I think it was the “42 knots” that I liked the best, so accurate and proud was Center to deliver that information without hesitation, and you just knew he was smiling. Walt keyed the mic once again to say, in his most fighter-pilot-like voice: “Ah, Center, much thanks, we’re showing closer to nineteen hundred on the money.”

For a moment, Walter was a god. And we finally heard a little crack in the armor of the Houston Center voice, when L.A. came back with “Roger that Aspen. Your equipment is probably more accurate than ours. You boys have a good one.”

It all had lasted for just moments, but in that short, memorable sprint across the southwest, the Navy had been flamed, all mortal airplanes on frequency were forced to bow before the King of Speed, and more importantly, Walter and I had crossed the threshold of being a crew. A fine day’s work. We never heard another transmission on that frequency all the way to the coast.

Colonel Tom Alison

When Alison left the SR-71 program, he had 966 hours in the Blackbird. He went on to become the Chief of Collections Management at the National Air and Space Museum. Alison died last June.We had two occasions to fly missions from Beale to Kadena that required very precise timing. On one, we were scheduled to pass a point off the coast of Petropavlovsk at the same time as another “Habu” [SR-71] was passing the same point in the opposite direction, heading from Kadena to Beale. After two air refuelings and three and a half hours of flying, we hit the spot within 10 seconds of our planned time and had the spectacular experience of seeing Lieutenant Colonels Bob Crowder and Don Emmons pass us, head on, about 5,000 feet below at a closure rate of over Mach 6.

On the second occasion, we were again going toward Kadena from Beale. My RSO, Lieutenant Colonel JT Vida, planned it so we left the third air refueling right on time, and we passed Majors Lee Shelton and Barry MacKean exactly “bang on” off the Soviet coast near Vladivostok. We continued on into Kadena and were followed moments later by Lee and Barry. The Blackbird watchers on Habu Hill had seen one SR leave, but somehow two came back!

Darryl Greenamyer

One of the best known race pilots in the world, whose 1977 low-altitude speed record (988 mph) in a modified F-104 still stands, Greenamyer was a Lockheed test pilot in the 1960s, flying A-12s and SR-71s.The idea of flying the SR-71 is you take off—or come off a tanker—and as best you can, get to 3.2 Mach number. With the SR-71 we’d fly out of Palmdale [California] or Edwards and fly to Florida in 58 minutes. At that time, I was living in Burbank, so I’d drive to Palmdale, have breakfast at a little café that I always went to, go to the factory where the airplane was, get in the airplane, fly to Florida, hit the tanker, fly home, and go to the same café for lunch.

Secrecy was pretty prime back then. Once I was flying an A-12 westbound from Florida, and I lost an engine over West Texas or New Mexico. So I started the descent, and I called them at Edwards to find out what they wanted me to do, and they told me, “Go ahead and land it in Nellis,” which is Las Vegas.

So I landed at Nellis. They had some remote taxiway pads to park, and this was probably left over from the war, when they would spread the airplanes around, so if somebody bombed the base, they’d only get one airplane. They taxied me out into the wilderness. But to get there, I had to taxi down the flightline, and it looked like the whole base was looking at me taxiing by.

Edwards Air Force Base had sent a colonel in charge of security to base ops to talk to the local security guy, and he was a captain. And the captain was so excited to have seen the airplane. The colonel from Edwards said, “I need to talk to everyone that saw the airplane,” and the captain said, “Well, everybody on the base saw that,” and the colonel said, “Well, schedule the auditorium.”

I didn’t go to the meeting, but the next day when I got in the airplane and got ready to take off, there were even more people on the flightline when I taxied by.

The majority of the flights were like flying a kiddie car. It’s a slick-flying, easy-flying airplane. You’re just sitting up, looking down at the contrails that the airlines are making and the curvature of the Earth, and it’s an exciting adventure.