A Tale of Two DC-10s

How one pilot overcame a flaw in the airplane—and one did not.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f0/b3/f0b3eb78-a98a-4356-91d8-72af1d6f97da/10f_dj2018_americann103aa_live_edit.jpg)

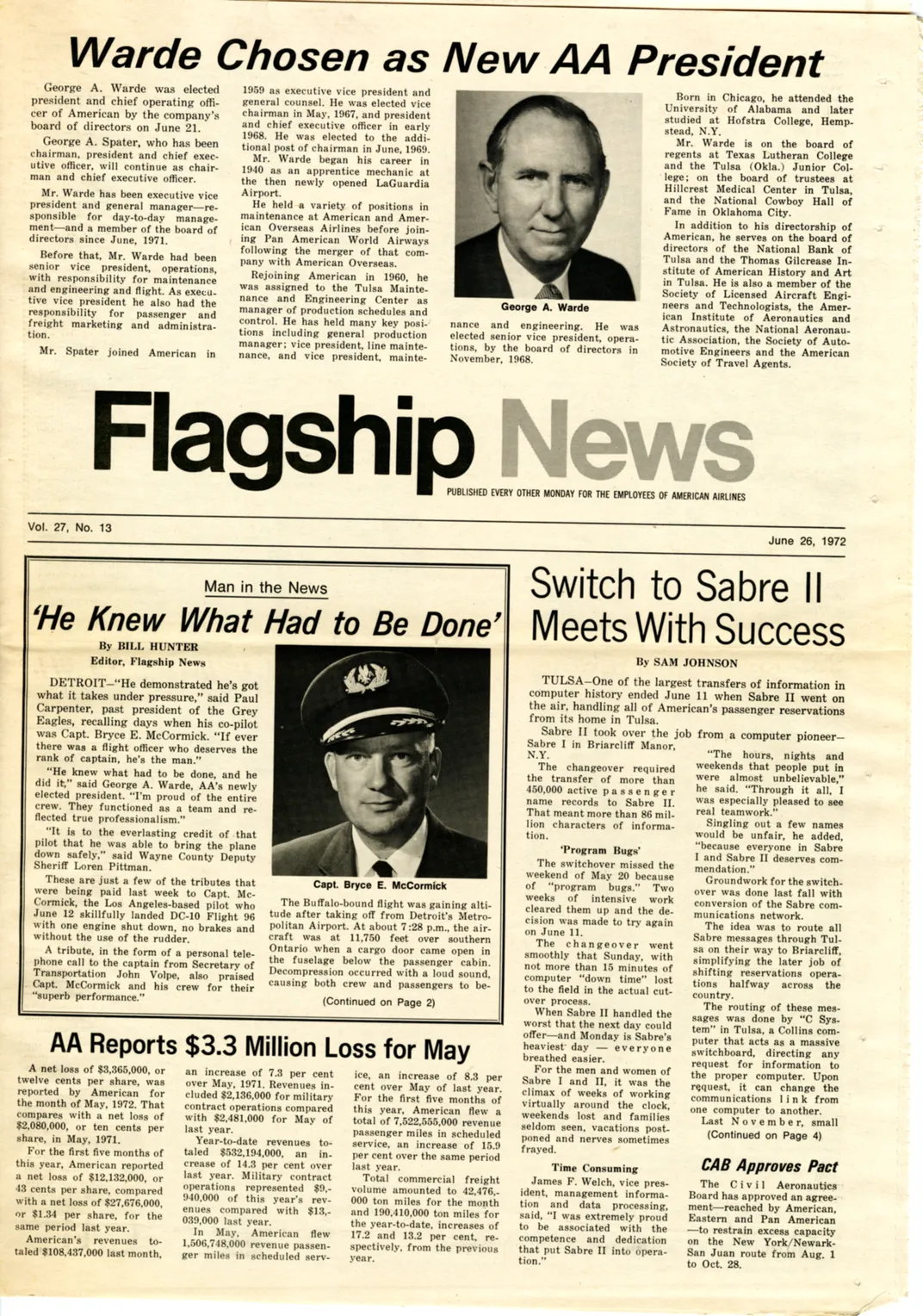

On June 12, 1972, American Airlines Flight 96, a DC-10, broke through a spotty cloud layer over the Canadian industrial city of Windsor, Ontario. Almost five minutes had passed since the wide-body jet had lifted off the runway at Michigan’s Detroit Metropolitan–Wayne County Airport at 7:20 p.m. Captain Bryce McCormick took a moment to appreciate the 180-degree view through the curved window of the cockpit, and leaned back and took a sip of coffee. Flight 96 was on its way to La Guardia Airport in New York City that evening, with a stopover in Buffalo. That morning, McCormick had flown the first leg of the flight, out of Los Angeles, so he let First Officer Peter Paige Whitney, 34, fly the takeoff from Detroit. All the gauges on the instrument panel registered normal. The autopilot was on, but Whitney kept his hands on the yoke out of habit.

Both pilots were well aware that their new DC-10 was only the fifth manufactured by McDonnell Douglas. The first had made its maiden flight in August 1970 and entered commercial service with American Airlines one year later, on August 5, 1971, on a round-trip flight between Los Angeles and Chicago.

McCormick was a veteran pilot who had accumulated 24,000 hours of flying time, while Whitney had almost 8,000 hours to his credit. The airplane was carrying just 56 passengers (the wide-body had the capacity for 206), plus 11 crew members, which included eight flight attendants and the three-man cockpit crew. (At the time, the DC-10 required a flight engineer.) Along with the passengers’ luggage, a casket carrying a corpse bound for Buffalo was stored in the cargo hold.

McCormick checked the radar and confirmed that no bad weather lay between Detroit and Buffalo. McCormick was an exceptional pilot. His presence in the cockpit inspired confidence. “He was the epitome of the perfect captain,” said Cydya Smith, the chief flight attendant on Flight 96. “He was very professional, yet he was warm and friendly and very respected, and respectful of the flight attendants.”

Both the “Fasten Seat Belt” and “No Smoking” signs had been turned off in the cabin. Passenger Alan Kaminsky and his friend Hyman Scheff unbuckled their seat belts and left their wives in the first class section to go play gin rummy in the forward lounge. They wanted to get in a few quick hands before the airplane touched down in Buffalo. Smith was out of her jump seat in the front of the plane before the “Fasten Seat Belt” sign blinked off. Following her usual routine, she walked to the galley and began to make coffee. “That’s when it happened,” she recalled. Exactly five minutes after takeoff, Smith was lifted off her feet by a powerful explosion. As the galley doors burst open, she could see entire sections of laminated ceiling panels falling into the passenger compartment, which was filling with a dense grayish-white fog. She could not hear the screams of the passengers. Instead, she felt as if she were enveloped in a gauzy silence.

As both pilots were jolted violently backward, a noxious cloud of charcoal-gray dust filled the cockpit, blinding McCormick, who feared the airplane had been damaged in a midair collision.

The actual cause of the unfolding calamity was something more insidious but just as devastating. A cargo door blowout in the hull had torn a gaping rectangular hole in the side of the aircraft, large enough to disgorge the six-foot-long casket, which tumbled two miles to earth, along with dozens of suitcases. Far worse, the explosive release of pressurized air had ripped out a large section of flooring in the passenger cabin directly above the gash in the hull. A hurricane-like wind was blasting through the length of the airplane. Flight attendant Beatrice Copeland had been knocked unconscious and lay trapped in the debris of the collapsed floor. Another flight attendant, Sandi McConnell, had barely escaped being sucked out of the airplane when the floor gave way beneath her; acting purely on instinct, she fought against the rushing air that threatened to pull her out into the sky. Without looking, she knew the lavatory door was directly behind her. It was her best chance for survival. Once inside, she closed and locked the metal door. She was safe for the time being, but cut off from rescue.

Alan Kaminsky remembers a “huge crunch” as his playing cards flew out of his hands and up into the air. Passengers shrieked as the DC-10 lurched to the right and fell several thousand feet.

The two pilots knew nothing about the gaping hole in the back of the airplane but were trying to contend with the stricken DC-10. As his vision cleared, McCormick took over the controls from his first officer. He had only seconds to regain control using a technique that had never been put to the test in an actual emergency.

Earlier that year, McCormick had been chosen by American to fly one of the new McDonnell Douglas airplanes. He had not been fazed by the jet’s size and engine power. What concerned him was one particular feature of the DC-10 that made it radically different from all the other big jets he had flown: its lack of a backup system to operate the airplane’s flaps, elevators, and rudder by hand in case the hydraulic system failed. In this regard, the DC-10 was very different from the DC-6 and -7 and the Boeing 707 and 727—all aircraft that McCormick had flown for more than two decades. All the older aircraft were equipped with reversion systems that gave pilots manual command of control surfaces if the hydraulic systems were knocked out. What would happen, he wondered, if all of the airplane’s systems were damaged?

He found the answer on a DC-10 flight deck simulator at the American Airlines training school in Fort Worth, Texas. Using the computerized simulator, McCormick spent hours repeatedly testing his alarming hypothesis of total hydraulic system failure and learned how to exploit the DC-10’s exceptional ability to fly on its engines without assistance from the rudder or ailerons, the surfaces that make the aircraft turn and bank. He also learned how to manipulate the engines to push the nose of the DC-10 up or down. Most jets have this ability to some degree, but McCormick discovered that the DC-10 was especially responsive.

The day his worst fears were realized, McCormick knew exactly what to do: He shoved two of the idle throttles fully forward, delivering a burst of enormous power to the aircraft’s wing engines, and felt them surge back to life. In response, the DC-10’s nose pitched up. McCormick had reversed the DC-10’s fatal descent. The returned engine power also bought him precious minutes to figure out how to steer the aircraft, which continued to yaw stubbornly to the right. He immediately flipped a switch to cut power to the fuel pump that fed the idle tail engine, taking it out of play and lightening the load on the elevators adjacent to the tail, making them slightly more responsive. Two of the four cables to the tail elevators had snapped. The ailerons were responding but sluggish. Without full hydraulic control, the DC-10 could not be banked in either direction by more than a gentle 15 degrees. Anything more would put it into a spin. McCormick decided that his best bet was to rely on the differential engine technique—boosting the thrust on one wing engine or decreasing it on the other—to slowly turn the DC-10 around and return to Detroit.

McCormick knew he would need ground controllers to give his crippled aircraft priority to land, and he contacted the control tower in Detroit: “Ah, Center, this is American Airlines Flight 96. We got an emergency.”

The response from Detroit control was equally terse. “American 96, Roger. Returning back to Metro?”

He hesitated. Where should they attempt to land? He briefly considered Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, where the runways are especially long and equipped with protective barriers in the event of a crash. But Detroit was closer. Better yet, the approach was clear. Detroit it was.

McCormick quickly reviewed their situation. “I’ve got no rudder control whatsoever, so our turns are gonna have to be very slow and cautious,” McCormick told Detroit control. All he could do was pray that the slats and flaps he needed to give the airplane lift at lower speeds would work when he began his descent.

The announcement had the desired effect. Whatever had happened, the pilot was not alarmed, and that inspired confidence.

McCormick’s biggest challenge would be to slow the aircraft enough to land safely. The DC-10 was approaching the runway at 184 mph, and McCormick needed to bring its speed down. However, without command of the rudder to keep the jet pointed straight ahead, McCormick might have to fly faster to ensure control.

At 7:40 p.m., 20 minutes after flying out of Detroit, Flight 96 was once again visible on the radar screen in the control tower. As the jet began its descent, it was Whitney’s job to monitor the aircraft’s critical sink rate, or rate of descent. As the ground rose up to meet them, the first officer began calling out the sink rate numbers with a sense of urgency that bordered on alarm. The rate was too steep and too fast. At the start of the descent, the jet was descending at a manageable 300 feet per minute. But as their speed slowed, the sink rate shot up to 500, 600, 700, 800, and finally 1,500 feet a minute. The aircraft wasn’t descending—it was falling. The only way to prevent a crash was to push the throttles forward and increase the speed. McCormick eased the throttles forward to deliver more power. And in a matter of seconds, the sink rate fell back to 800 feet per minute and the jet’s speed shot back up to 184 mph.

When its tires hit the concrete runway, the DC-10 was speeding like a race car; the jet veered off the runway to the right, where it bumped across taxiways and grass medians on a collision course with the main terminal. McCormick reacted by throwing the number 1 and 3 engines into reverse thrust, but even that could not counteract the airplane’s momentum.

Whitney reached over and took control of both throttles, simultaneously pushing the right wing-engine throttle full forward and the left wing-engine throttle into full-reverse thrust, delivering 10 percent more power and forcing the jet to swing to the left, on a return course to the runway. It hurtled along, with two sets of wheels on the runway and the other two off. When it finally stopped, half the wheels were on concrete and half on grass, with more than 980 feet of runway to spare.

A vastly relieved McCormick gave the order to shut down the two engines. Smith and the other flight attendants helped the passengers at the emergency exits. After the six chutes had inflated and the first passenger slid down to safety, it took only 30 seconds to get all 56 passengers off the airplane. McCormick gave his final order to evacuate the cockpit; he and Whitney were the last to exit.

As emergency vehicles came rolling up, red lights flashing, the crew members all wanted to get a good look at the mysterious hole in the fuselage. There it was, easy to see even in the deepening twilight: The large aft cargo door was gone. Above the opening, a jagged piece of metal curled upward, as if it had been peeled back by a giant can opener.

The entire episode on Flight 96, from its explosive onset to the perilous landing, had taken place in less than 30 minutes. The jet’s aft cargo door had separated from the aircraft with explosive force at 11,750 feet above sea level. How and why the door had blown out in midair was a mystery that needed to be solved as quickly as possible.

The accident investigators were in luck: The same day as the accident, Ontario police contacted airport officials about an airplane door—and coffin—that had landed in a cornfield outside Windsor. After going over every inch of the door, the investigators made a shocking discovery: The airplane had taken off with the door closed but not secured. As the airliner ascended and internal air pressure increased to a critical level, it was only a matter of time before the large cargo door would give way and blow out.

And there was another design flaw: The section of the cabin floor above the cargo hold lacked pressure relief vents that would have permitted the air from the cabin to flow through without ripping the floor apart. When the National Transportation Safety Board issued its final report, it implicated both the door and the floor.

***********

The Federal Aviation Administration agreed not to issue an airworthiness directive, but quietly told McDonnell Douglas to fix the problem. NTSB investigators recommended modifying the DC-10’s cargo door and cabin floor; McDonnell Douglas claimed that what happened to Flight 96 was an isolated incident. (The problem was actually intermittent and ongoing.) Less than two years later, a sudden blowout tore through Turkish Airlines Flight 981 from Paris to London. That DC-10 crashed in France; none of the 346 people on board survived.