Build-It-Yourself Helicopters

If you have 700 hours to spare and can shim a rotor assembly to within .001 of an inch, here’s a hobby for you

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Helicopters_FLASH_AUG2010.jpg)

When someone slaps down a hundred grand for a vehicle—a cigarette boat, say, or a sports car—there is usually some kind of red-carpet handover: a hearty handshake along with the keys, then a captain’s cap or a bottle of wine.

Not when the vehicle is a kit-built helicopter. In March 2009, Rod Harms’ helicopter-to-be arrived in eight crates stacked outside his ranch-style house near Pekin, Illinois. The delivery service left them in the nearest open space: the road. “Not by the road, in the road,” says Harms. He called a friend to help hustle them out of traffic. The delivery, just eight days after the order had been placed with RotorWay International in Arizona, caught Harms with his hangar incomplete.

Four months later, he has finished the hangar, along with much of the aircraft’s frame and cabin. Bright, spacious, equipped with workbenches, power tools, and a concrete floor, Harms’ hangar is close to his house: His wife signed off on the project on the condition that he not build it after hours at his auto-body shop—she had the wifely intuition that she might not see him for months of Sundays.

One big crate stores dozens of lumpy, shrink-wrapped cardboard sheets. This is how RotorWay packages smaller parts like snap rings, pins, nuts, and bolts, which if shipped en masse in plastic bags could wind up in the wrong holes. Every part has a unique number to match a step in RotorWay’s notebooks and DVDs.

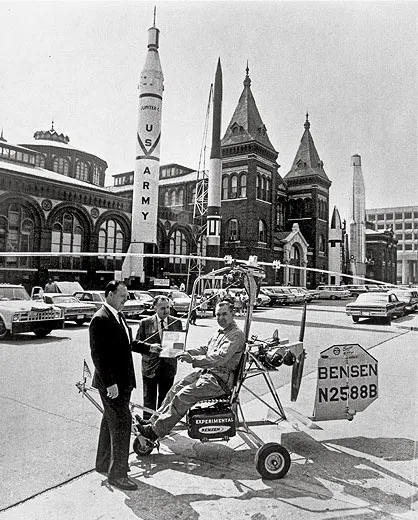

First clamoring for notice in brash, optimistic magazine ads of the 1950s (“Easy!” “Fun!” “Anybody who can ride a bicycle can fly this!”), the first viable home helicopter products came from Buford J. Schramm and Robert Everts, who designed the Scorpion (first named the Javelin) and began selling it in 1967 to hobbyists who wanted recreational rotary-wing flight but didn’t want to go the gyrocopter route with Bensen, Barnett, and other brands, or couldn’t afford a factory-built model. Two-seater Scorpion and later Helicom kits were challenging even for the mechanically gifted, but cost less than $7,000 in 1975, one quarter the price of a Hughes 300 two-seater. Although this entry-level niche took a hit when the $40,000 Robinson R22 production helicopter debuted in 1979, the homebuilt industry still sells hundreds of kits per year for construction under the Federal Aviation Administration’s amateur-built, experimental category.

According to Homer Bell, who taught himself to fly in a two-seat RotorWay Scorpion Too in the first wave of kit-copter enthusiasm and is now a consultant to home helicopter builders, “There’s no single type of customer. They’re all over the place—doctors, farmers, not just people who don’t have enough money to get a production machine.” The kit helicopter community is much smaller than the fixed-wing kit builders, but the skills cross over: It’s not unusual to find helicopter builders whose stables house a Van’s RV-10 or other homebuilt airplane.

When all checks are done and forms completed, the customer finds that he or she is the manufacturer of a new aircraft, as well as its mechanic, notwithstanding the lack of an airframe-and-powerplant license. This has its pros and cons. On one hand, the sellers of such kits can be agile and adaptive, which helps keep production costs low. They can choose to ship whatever engine suits their fancy, or can leave the choice to the buyer, who could use a rotary engine from a Mazda RX-7 if he could adapt the power train. Since the FAA does not certify unassembled kit helicopter models as airworthy, it offers no opinion on such matters. On the other hand, in case of mishap, the customer’s number-one legal target is himself, as manufacturer and chief mechanic.

The word “kit” may conjure up childhood memories of assembling a Revell model from a cardboard box, building up each rotor with blades and a tube of glue. But when it comes to full-size helicopters, “build” is a more appropriate verb than “assemble.” While some parts must be cut, trimmed, or drilled, no arcane skills are necessary. It helps to start with a well-equipped workshop, a methodical style, and a familiarity with engines. Some companies, like Hummingbird maker Vertical Aviation Technologies, let customers add bucks to move up to a “quick-build kit” that cuts down on workshop time. But speed is not the point. Think of a big watch: RotorWay wants its customers to wield a micrometer and paper-thin shims to bring the hub and attached rotor blades (which stretch 25 feet tip to tip) to within .001 inch of perfect center.

“Some people should only be building wheelbarrows,” says Al Behuncik, a RotorWay dealer in Alberta, Canada. “Their attitude is, ‘Well, it looks good enough to me!’ ” Behuncik spent 27,000 hours building and flying the four aircraft in his “copter barn,” coming up with improvements for the factory to adopt. Meticulous in his work, he has the gentle manner of a wrench-wielding Mr. Rogers, but his tone changes when discussing problems that are, in his view, easily avoidable. Behuncik says he sees two personalities that tend to get into trouble: “One is the person with no mechanical ability. The other is someone who just wants to get it done.”

While an old hand like Behuncik plans on spending 350 hours to bring a new A600 Talon from crate to flight, a newcomer is likely to spend twice that, or more. I heard tales of people for whom a decade of tinkering wasn’t enough. (Ads for the notorious Mini-500 single-seater kit from Revolution Helicopters claimed that owners could build one in 40 to 60 hours, but after a spate of well-publicized fatal crashes, hard landings, and hard feelings, Revolution folded in 1999.)

Five companies dominate the North American market. Three make kits in the United States—RotorWay sells the Talon; Eagle R&D, the Helicycle; and Vertical Aviation Technologies, the Hummingbird— and Canada has two brands, Safari and Mosquito. (B.J. Schramm founded RotorWay in 1961 and Eagle R&D in 1998; he died in 2004 in the crash of a Helicycle, but his wife heads his second company.) Kits with engines sell for about $28,000 for the entry-level, single-seat Mosquito to $200,000 for the four-seat Hummingbird, a kit version of the Sikorsky S-52. RotorWay dominates the field, having shipped its first kit helicopter, the Scorpion, in 1967.

HOMER BELL IS A HOSPITABLE soybean farmer who moonlights as a traveling troubleshooter for kit-helicopter owners; they know him by first name rather than last. Since Bell doesn’t hold an airframe-and-powerplant license, his official role is more mentor than mechanic.

Bell spent two and a half years on his two-seat RotorWay Scorpion Too, flying it at the 1975 Oshkosh show. B.J. Schramm had priced the Scorpion low enough to attract newcomers like Bell: $6,900 for the complete kit, including an Evinrude outboard motor. But Scorpion buyers opened the boxes to find raw material waiting to be cut, bent, and joined into a fuselage per the blueprints. Would-be pilots besieged Schramm’s RotorWay firm for help.

“He was taking calls 24/7 from customers,” recalls Bell, who was a technician for National Cash Register when Schramm invited him to be a dealer and earn commissions. “Pretty soon I was spending three to four hours a day on the phone, into the evening, and also working third shift,” Bell says. “I told B.J., ‘I’m spending too much time on this. Let me out of this dealer deal.’ ”

The solution: Bell would keep offering aid and comfort to kit builders but charge for it. In 1984 he began inviting fellow helicoptrians to his house in Waynesville, Ohio. After three years, the July “copter meet” outgrew the neighborhood, and Bell bought a 200-acre farm, where he lives today, raising corn and soybeans, and putting aside helicoptering for the harvest each fall.

In the first years, Bell’s fly-in was more of a drive-in, in which he hosted unflyable helicopters that arrived on trailers. Some of those that looked ready to go had owners who were reluctant to make the first flight without a nose-to-tail rotor inspection by Bell and other veterans. “It was more of a seminar back then,” Bell says. “They’d bring their machines and we’d critique ’em. We’d help on certain things, like building up blades.” Because today’s kit-builders have much more help available—online forums, factory checkouts, paid builder assistance, aftermarket parts, DVDs, shrink-wrapped parts—and more components like rotor blades are sold already fabricated, needing only attachments, few helicopters pull up at Bell’s door in dishabille anymore. “Every night the Helicycle guys go to their site on Yahoo,” says John Murphy, who owns a one-seat Eagle R&D Helicycle. “Minutes after somebody has a problem, it’s on the pilots’ site.” Users then respond with a solution or start a fix-it discussion. “So that gives you a warm fuzzy feeling.”

Finishing a helicopter both completes a challenge and begins another. Let’s assume that the new two-seater is rigged and balanced perfectly. Assume also that a certified flight instructor is on hand. Even so, the first days of practice are likely to be frustrating—even scary—because it takes time to develop the reflexes and multi-tasking skills unique to helicopter piloting. Once skids depart ground, pilots must make constant, small corrections on the controls without delay. Early kit-built rotorcraft had such a high crash rate that an FAA inspector in a July 1970 Popular Science article called them “the most dangerous type of experimental aircraft in use today,” and warned that 95 percent of the crashes happen at low speeds near the ground. It was a sobering change in tone from that found in earlier magazine articles. One reason for trouble among novices is the phenomenon called dynamic rollover. If a helicopter pivots around a landing gear during liftoff or one landing gear makes inadvertent contact with the ground while sliding sideways, the thrust of the main rotor will flip the machine on its side, requiring thousands of dollars in repairs.

The major brands of kit helicopters share the layout of Igor Sikorsky’s classic VS-300 prototype of 1941, which combined a single main rotor for lift with a small, vertically mounted rotor on a tailboom to offset the main rotor’s torque. Flight controls on kit-built helicopters mimic those on their production counterparts. Two “anti-torque” foot pedals control the pitch of the tail rotor and point the nose left or right; a collective lever connects to the main rotor and urges the machine up or down; and a joystick at knee level called a cyclic adjusts the main rotor to tilt the helicopter so it flutters off in the desired direction.

Orv Neisingh is an independent Missouri-based expert who has been training pilots on RotorWay helicopters for 10 years, and now holds an airframe-and-powerplant license that allows him to sign off on repair work during his field visits. That elevates him to one of an elite corps of consultants. Liability concerns, the small size of the kit-copter market, and the inclination among builders to perform their own repairs keep the number of licensed mechanics who deal with kit-built helicopters low. Neisingh’s service comes with a wise skepticism. Before scheduling work where he would fly another’s kit helicopter for training or testing, he requires the new customer to fill out a long and sobering checklist.

RotorWay customers can also go straight to the factory. RotorWay runs its flight school out of Stellar Airpark in Chandler, Arizona, in three sets, or phases, of classes. Each phase takes up to a week. Phase 1 is mainly for hover practice, which alternates with school on documentation, maintenance, and rigging. According to Robin Wactler, director of the flight school, the best time to come for Phase 1 training is near the end of construction, but before the main rotor is complete.

Nearing the end of their build, Helicycle owners are required to spend a week with an Eagle R&D representative like Doug Schwochert of Burlington, Wisconsin. Schwochert’s house call comes at an extra charge but it isn’t optional, since he brings a crucial pair of main-rotor bearings available only from the factory. (After B.J. Schramm liquidated his interest in RotorWay and founded Eagle R&D, it was Schwochert who convinced him that a turbine instead of a piston engine should be the Helicycle’s standard powerplant.) Schwochert inspects each part before lighting off the turbine, followed by a series of adjustments before test flights begin.

A refurbished Solar T62 gas turbine once used in generators is the standard engine, accounting for a quarter of the kit’s $39,800 price. Its power section spins at 62,000 rpm, more than 1,000 times a second. Gearboxes bring this down by a factor of 20 to suit the tail rotor, and still further for the main rotor. Though the Solar is rated for 160 shaft horsepower, Eagle has cut fuel flow, holding it to 90 shaft hp for longer life.

IT’S JUST AFTER LUNCH in the RotorWay school hangar, and the talk is of grease: the red variety, in a big shiny grease gun, and where to point it. A RotorWay 162F Executive (superseded by the A600 Talon in 2007) has grease points under the main rotor and around the tail rotor drives. Explains Robert Preston, the company’s factory instructor pilot, owners will be wielding the gun every 25 hours of routine operation, and will be checking air and fuel filters, changing oil, and tightening the chain drive and the three rubber belts that drive the tail rotor.

When explaining how to tighten bolts, Preston advises student Don Pool: “Remember, this is an aluminum block and steel wins every time, so don’t apply more torque on the bolts than necessary—no monkey strength allowed!” With time out for flight training, Preston spends the week shouldering through a long list of RotorWay-specific techniques.

Pool is a high-time corporate jet pilot (and licensed airframe-and-powerplant mechanic) who seems content with setting aside time and money to learn the hobby—up to a point: He wants to earn his hover endorsement this week, rather than having to come back later to finish Phase 1. Preston warns him that most students need to come back for an additional week of training before moving on to Phases 2 and 3. In all, someone new to helicoptering could require four trips to Chandler, but at the end he or she will have a gilt-edged rotorcraft license.

Patience and good workmanship is key, says Al Behuncik. “The helicopter is a wonderful machine, but if it’s not built correctly it can and will kill you. There’s no excuse for anyone building a shoddy machine, because the instructional books and videos show you exactly how to do it.”

What do people do with their helicopters upon completion, besides attend fly-ins? As these are experimental craft, commercial use is prohibited. Rod Harms plans on using his Talon for two-hour jaunts to Chicago, packing luggage in a cargo compartment that fits under the cabin. Joe Goetz uses his Helicycle as a volunteer eye in the sky for the sheriff’s department in Maricopa County, Arizona; he enjoys the sense of mission and the fact that when on duty he can land at places otherwise off-limits to helicopters, like downtown parking ramps. Norm St. Peter and his wife use their float-equipped Hummingbird to fly from Florida to northern Maine, where they fish remote lakes.

Checking back with Don Pool at the end of his week at RotorWay, I learn he has beaten the odds and won his hovering endorsement. This opens the way for training at home, followed by more work at Chandler to finish his rating. Then he plans to load his Executive on a trailer and haul it out west behind an RV. Where the pavement stops and the desert begins, he’ll climb in and head for the hills.

James R. Chiles is the author of The God Machine: From Boomerangs to Black Hawks, The Story of the Helicopter (Bantam Dell, 2007).