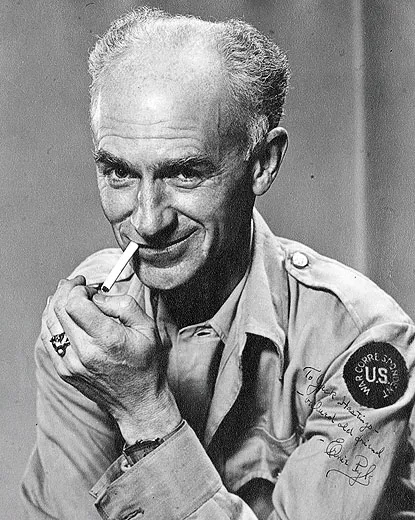

Byline: Ernie Pyle

The country’s best-known war correspondent learned his trade as an aviation reporter.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Byline_Ernie_Pyle_11-01-11_5_FLASH.jpg)

For Americans in the 1940s, Ernie Pyle was as much a part of World War II as war bonds. His newspaper columns made readers feel that they were witnessing the action on the frontlines and were written in a voice that seemed to speak to each one personally. “I wish you could see just one of the ineradicable pictures I have in my mind today,” Pyle wrote from northern Tunisia in May 1943. “In this particular picture I am sitting among clumps of sword-grass on a steep and rocky hillside that we have just taken.” Of the soldiers with him, Pyle wrote, “They are just guys from Broadway and Main Street.” The vivid language in the column is typical:

“For four days and nights they have fought hard, eaten little, washed none, and slept hardly at all…. Their walk is slow, for they are dead weary, as you can tell even when looking at them from behind. Every line and sag of their bodies speaks their inhuman exhaustion.”

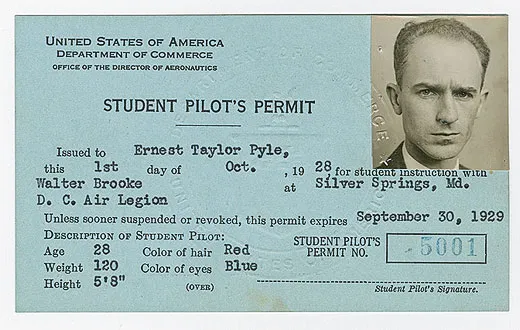

Pyle became famous for the sympathetic dispatches he filed while traveling with the infantry in North Africa, Europe, and the Pacific during World War II. But long before he became a hero of the American foot soldier, Pyle was an aviation reporter—the first in the United States to write a daily aviation column. Starting in 1928 (just 10 months after Charles Lindbergh’s solo crossing of the Atlantic captured the world’s attention), and for the next four years, Pyle’s column was a staple of the Washington Daily News.

He wrote about aerial mapping, the perils of night flying, airline safety, and engine and airplane design and profiled cropdusters, glider pilots, military aviators, parachutists, and barnstormers. Based in Washington, D.C., Pyle regularly visited nearby Hoover and Bolling Fields (today the sites of the Pentagon and a Navy-Air Force base), the Washington Naval Air Station, and a handful of smaller airfields. He spoke frequently with senators and congressmen; Jimmy Doolittle was a friend.

Once, the editor of the Daily News decided to introduce Pyle to Amelia Earhart. The pilot stopped him, explaining that the two were well acquainted. “Not to know Ernie Pyle,” she said, “is to admit that you yourself are unknown in aviation.”

Pyle hadn’t planned to become a journalist. He’d wanted to serve in World War I, but he was too young. In 1919, he enrolled at Indiana University with a vague plan to study economics. Overhearing another Indiana farmboy touting journalism as an easy major, Pyle signed up. He joined the staff of the Indiana Daily Student, reporting on fraternities, local news, and sports, even following the university’s 12-man baseball team to a demonstration game in Japan.

He left the university in January 1923 without a degree, taking a job as a reporter with the La Porte (Indiana) Herald. Four months later, Pyle made the jump to the Washington Daily News.

“The young staff was fluid, to say the least,” wrote Lee Miller, Pyle’s managing editor and first biographer, in 1950. “Shortly before Ernie’s arrival there had been a succession of three city editors in a single day.”

The 12-page newspaper, part of the Scripps-Howard chain, had been launched just 18 months earlier. Its editorial office, wrote Miller, was “a shabby, littered, ill-ventilated rectangle congested with secondhand desks [located] a few blocks from the White House.”

Although hired as a reporter, Pyle was soon also writing headlines and copy editing. By 1927 he was so bored that he asked Miller if he could try writing an aviation column in addition to his other duties. (He had developed a “veneration for aviators that was reminiscent of his [childhood] devotion to automobile racers,” wrote Miller.) After finishing his normal shift at about 2 p.m., Pyle would make the rounds of the airports and airfields, looking for stories. Then he would head home to write his column, and turn it in the next morning.

The first “D.C. Airports Day by Day” column appeared without a byline on March 26, 1928. After giving the day’s flying weather (“Gentle winds south and southwest up to 1000 feet”), Pyle described joyrides at three of Washington’s airfields: “Scores of passengers hopped off from Hoover Field, Capital Airport and College Park Field for short flights over the city. Hundreds of others, tempted by the ideal weather, lingered at the fields to watch the ships come and go.” He even worked in a little drama: Army pilot Ross Hoyt broke a propeller and smashed his undercarriage while landing in a plowed field, and Herbert Fahy, chief pilot at Capital Airport, was likened to the famous Lone Eagle: “Like Lindy, [Fahy] ate a sandwich as he flew, late in the afternoon. His plane, a Ryan cabin ship, almost a duplicate of Lindy’s Spirit of St. Louis, attracted many embryo fliers.”

The column was a success; by April, Pyle had his own byline, and in May 1928, he was relieved of his copy-desk duties and free to spend all of his time covering aviation.

“Pyle was finding his voice,” says Owen Johnson, a journalism professor at Indiana University who is editing a collection of the reporter’s letters. “Aviation was a pioneering world where things were changing, and that made it very exciting to write about. And Pyle did his best writing when he was excited about something. His letters make it clear that during this period, from 1928 to 1932, aviation was the center of his life.”

Just as Pyle would later describe the day-to-day life of the infantry to Americans on the homefront, he used his aviation column to portray the world of aviation to an air-minded public.

And the public was eager for details. Pyle wrote about flying in a twin-engine Fokker bomber and conducting searchlight tests; his trip in a Ford Tri-motor, flying at 156 mph over the Transcontinental Air Transport’s air-rail line between New York and Los Angeles; and what it was like to take a hop in a Pitcairn-Cierva Autogyro (“We went forward so slowly that you could hardly see the wings pass objects on the ground, but it seemed we were settling very rapidly. Very much like going down in an elevator”). He traveled to Cleveland and Chicago to cover the National Air Races, to Akron to report on the future of the zeppelin (“For long-distance hauling there is nothing in the world as fast, as safe, or as efficient”), and to St. Louis to attend a joint meeting of the Society of Automotive Engineers and the Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce.

While captivated by aviation, Pyle found publicity flights and endurance records distasteful; his heroes were airmail pilots. On June 30, 1929, he wrote a tribute to one: “Bill McConnell was in to see us yesterday. That name probably doesn’t mean much to you, for Mac hasn’t done bigger and better things in the publicity lines.

“He is an aviator, but he has never been to the North Pole, or the South Pole, or flown across the ocean at midnight with a pig in his lap, or stayed in the air a week without changing his socks.

“No, all he ever did was fly the night air mail between Cleveland and Cincinnati every night for 34 consecutive nights last winter.”

In these early columns, Pyle developed the easy, homespun style that would later characterize his World War II correspondence. Of Lieutenant Jimmy Doolittle running a 1929 radio beacon test: “If you had been at College Park Field just at dusk yesterday, you would have seen a little man, all stuffed and beclothed until he looked like a big man, waddle into his airplane and fly away into the northern darkness.”

Pyle wrote about pilots by day and socialized with them by night, often in his tiny second-floor apartment on N Street in southwest Washington. The airmail pilots were so comfortable with the slight, redheaded reporter that if they were forced to land due to bad weather, they’d call the postal service first and Pyle second, to give him the story.

Miller wrote that in 1929, “a young naval lieutenant, Apollo Soucek...was trying to set an altitude record. When he landed at the Naval Air Station after his first high flight and asked for a cigarette, Ernie was the first to hand him one. Another day, following a second flight, Ernie was there again with a cigarette. Still later, ‘Soakum’ stepped from his plane after another altitude flight—but Ernie wasn’t there. Soucek refused to smoke until Ernie was located, at Washington-Hoover Airport across the river, and rushed by taxi to do the honors.”

Pyle’s instincts were not always right. After flying in one of Eastern Air Transport’s big Curtiss Condors in November 1931, he offered this summary: “We think your airplanes are the most comfortable in the world, your pilots without peers, and your flying hostess idea a lot of foolishness.”

In 1940, the newspaper suggested a European trip; Pyle, by now a national columnist for Scripps-Howard, was lukewarm. Reluctantly, he decided to report from England, arriving in a blacked-out London on December 9, during the Blitz. His columns, eventually published as the book Ernie Pyle in England, were successful from the start; First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was a fan, telling readers in her own newspaper column, “I don’t know whether any of you are reading about Ernie Pyle’s trip to England with as much interest as I am, but I have read everything since he left….”

After England, Pyle thought about following the American air forces: “I could become sort of an adopted unofficial biographer for them,” he wrote Miller. “In a way I could revive the old aviation column....” He ended up in Algeria instead, just two weeks after the invasion of Africa, his first columns covering the Allied troops that had made the original landings, and the hospital units that cared for the wounded. Pyle told Miller he found these columns “inadequate,” but they offered something—the empathetic voice, perhaps—that readers at home seemed to need.

Says journalism professor Owen Johnson, “I have on my desk right now a series of four scrapbooks that include Pyle’s columns from World War II, and it’s not the first set that I’ve received; a number of people saved them.” Certainly there were other journalists writing excellent stories about the war, but no one else focused on the men who were waging it. “One of the things about Pyle that made him better known among the troops was that Stars and Stripes printed his column and not so much reporting by other people,” Johnson says. “So the soldiers would write home, saying, ‘If you want to understand what it’s like, read Ernie Pyle [and enclose a clipping from Stars and Stripes],’ and at the same time you have the families sending the columns to the troops so you’ve got this back and forth that no other correspondent had.”

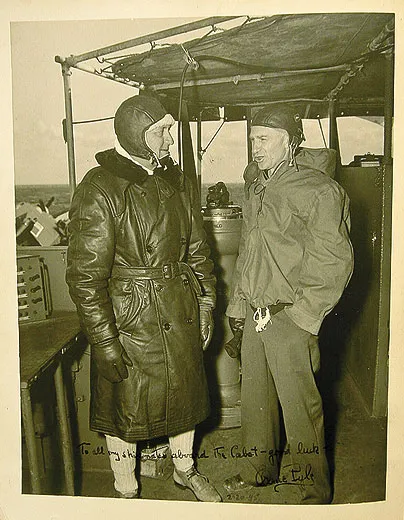

After North Africa, Pyle headed to Accra, Ghana, to cover, he told Miller, “the biggest American aerial operation anywhere outside the United States.” He was shepherded around by a friend, Colonel C.R. Smith. Learning that Pyle was in the audience during a USO performance there, the troops roared “We want Ernie!” Smith wrote in a letter home that the ovation was so big that “even the stars were jolted.” Pyle would eventually travel to Italy, back to England, and on to France, and then to the Pacific Theater. By 1945, almost 700 newspapers carried his byline.

During the war, Pyle would continue to run into the people he had met on the aviation beat in Washington, D.C. In 1942, he would catch up with his old friend Ira Eaker, whom he’d first met in 1929 when Eaker was chief pilot on an endurance flight in the Army Air Corps’ C-2A Question Mark. Eaker would become a U.S. Army Air Forces major general, and the commander of the Eighth Air Force. Pyle would also cross paths with General Jimmy Doolittle, whom he hadn’t seen in years; they would spend a long evening reminiscing over a bottle of rye. When Pyle was on a rare trip home to Albuquerque in 1944, he was paid a visit by Helen Richey, who had set an endurance record in 1932 by staying aloft for 10 days; now with the Women Airforce Service Pilots, she dropped in on him while she was ferrying an A-20 across the country.

But all of that was in the future. In 1932, after four years on the aviation beat, Pyle reluctantly accepted the position of managing editor at the Washington Daily News, and on June 26 he wrote a column, titled, simply, “Goodbye”—his last aviation column. “I have flown nearly 100,000 miles, landed in far away spots all over the United States, and even outside of it. Better than that, I have made wonderful friends; friendships that will last a lifetime. And, just to keep from sounding sentimental, I might add that I have known a lot of very ornery people in aviation, too. But thru it all I have had one grand time.”

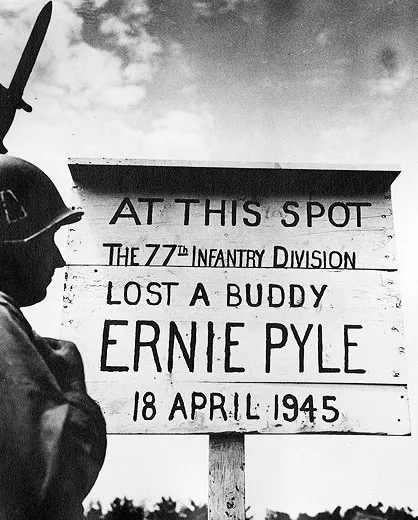

Members of the aviation community invited Pyle to a small ceremony at Washington-Hoover Airport, where Amelia Earhart presented Pyle with a watch. It was on his wrist 13 years later, on April 18, 1945, when he was shot and killed by a Japanese sniper on the island of Ie Shima, off Okinawa.

Rebecca Maksel is an Air & Space associate editor.