Can This P-38 Be Saved?

Lockheed P-38 Lightnings brought many a pilot home. This pilot would like to return the favor.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Arch_Vapor_Flash_ON09.jpg)

On June 27, 1944, the U.S. 5th army had the Germans in northern Italy on the run. That day, Army Air Forces First Lieutenant David Toomey, a pilot for the 3rd Photo-Reconnaissance Group, took off from an airfield at Tarquinia, 50 miles north of Rome, to photograph German fortifications along the northern perimeter of the Arno River valley, from Florence to Pisa. It was his second mission over the territory in a week. Toomey flew a Lockheed F-4 named Duckypoo, the crew chief’s pet name for his wife. The F-4 was a photo-reconnaissance version of the P-38 Lightning. To get good tactical photos, pilots had to fly the airplane low, and to keep from being shot down, they had to fly it fast. His camera was mounted on the right side of the fuselage, so to photograph the northern area of the valley, Toomey would have to fly west at 1,500 feet. His approach took him north along the coast, then inland just south of the Arno. He’d head east 50 miles to Florence, all at treetop level to avoid German radar, pull a U-turn, and come back along the valley to Pisa. That was the plan, anyway.

Today, Toomey lives on Camano Island, Washington, and the P-38 he flew that day lies on the floor of the Tyrrhenian Sea, a few miles off Italy’s coast. Hoping to find someone to confirm its location and finance its recovery, he and his colleagues have knocked on doors from Washington, D.C., to Washington state. The National Geographic Society was interested, but later decided not to pursue a project. Representatives of the Flying Heritage Collection, Paul Allen’s museum in Everett, Washington, said that Allen purchases only airplanes that fly. Kermit Weeks, owner of Fantasy of Flight, a collection of flying historic airplanes in Polk City, Florida, told Toomey he already has a P-38. Even The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery declined. “They told me I’d best let Duckypoo rest in peace,” he says.

The following is adapted from Toomey’s typewritten memoir, Tall Tales and Vapor Trails.

The day was pleasant but windy and slightly overcast. I took off at 0830 and headed Duckypoo out to sea and up the coast. Although Duckypoo was our oldest airplane, she was our fastest—an old P-38F that had been stripped down and equipped with a pair of more powerful Allison V-1710 turbo-supercharged engines, each of which churned out more than 1,400 horsepower. Speed, and the ability to fly at both low and high altitudes, made the P-38 a natural for photo-recon. Fighters, as they say, win battles; recons win wars. General Mark Clark, commander of the U.S. 5th Army, wanted our latest photos on his desk every morning at 0600.

In the F-4, we flew mostly two types of missions: mapping runs and pinpoint runs. In mapping runs we flew back and forth at 25,000 feet, photographing an area of 400 or 500 square miles. Our cameras were loaded with 180 feet of 12-inch-wide film, which meant we could make a total of 180 exposures. Each exposure covered an area of nine to 16 square miles and provided amazing detail.

On pinpoint runs, we flew to an isolated point of interest, such as a bridge, tunnel, or highway intersection. These missions required precise navigation to identify the target, which we did by correlating rivers, railroads, and towns with what we had on the map. Then it simply required three or four good exposures of the target—at least two were needed to produce the third dimension.

Today’s mission, though, was the rare and voluntary third type: a dicer, from the word “dicey,” which our British friends used for “risky.” It was low and fast and left no room for error. It often put you face to face with the enemy.

I had transferred to the P-38 just six months earlier, from the copilot seat in the lumbering B-17 bomber. My love affair with the P-38 had begun at age 17, when I spent the summer of 1940 living with my grandmother in Portland, Oregon, cutting grass and brush for the city. On my days off, I went to the Portland Army Air Base to watch the airplanes take off and land. A squadron of P-38s was stationed there, I believe flying submarine patrol over the mouth of the Columbia River. As the airplanes returned to their base and “peeled up” for their landings, they were poetry in motion. I became fascinated by their sleek, twin-boom profiles and their graceful performance. Someday, I vowed, I was going to fly a P-38.

Four years later, here I was, flying the sleek Lockheed. On my first solo flight, in January 1944, I had left the ground at 100 mph, but as I retracted the landing gear, the airplane seemed to jump out from under me. I went from 100 to 250 mph so fast I couldn’t believe it. I started climbing, and as soon as I got my coolant controls set I nearly fell over—my altimeter said 10,000 feet. Even when I slowed the airplane down I was going 250 mph. Most of the time my airspeed was around 300. (Imagine going a mile in 12 seconds, and you can understand 300 mph.) I saw 350 several times, and in short dives, I even reached 400.

Speed was our only defense. The P-38 could generally outrun any of the Germans’ airplanes, in both a shallow climb or a dive. One day a group of Messerschmitt Bf 109s jumped me, and I outran them to the coast. I think I made 500 mph, going downhill. But I hit serious turbulence, and thought the airplane was going to come apart. The main spar between the engine booms and the gondola popped a bunch of rivets. When I got back it was a wreck, and they junked the airplane. The crew chief told me (jokingly) that I’d pushed on the throttle handles so hard I’d bent them. Bottom line: The most survivable photo-recon pilot was the one who was the most scared.

On this mission, I flew as close to the water as I could. To conserve fuel, I flew through the strait between the Isle of Elba and the mainland, rather than detouring around the island. I found the initial point I’d used before, then cut across the coast. The minute I crossed the frontlines, I’d always get a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach. In football we used to call it the “kickoff feeling.” For me, it usually lasted up until I started my first run over the target. It was especially true for us in photo-recon, because we were always alone, with no wingman or squadron mates to help watch for flak or enemy fighters. You had to do it all—fly, navigate, survey, operate the camera—and never a friendly face nearby to buck up your spirits.

A couple of miles later I crossed the main highway and approached a row of tall cottonwood trees. I hopped over them and dropped into a small meadow, which I recognized. At once I realized that something was wrong—something in the meadow had changed. A row of trees to my right hadn’t been there before. Too late, I realized they were German heavy guns elevated vertically and camouflaged. The Germans must have seen me coming; they started shooting at me with everything they had. I even glimpsed one soldier firing at me with a pistol. It was a miracle I made it through the ambush. Something, either a bullet or shrapnel, came through the canopy and cut me over my right eye. I remember wiping blood from the small wound and looking stupidly at the hole in the plexiglass.

The soldiers below and in front were all firing at me. I had no choice but to run their gauntlet. Suddenly one of my engines was on fire, and the cockpit began to fill with blinding smoke. I jettisoned the canopy. As soon as I could see, I banked the airplane sharply and, barely avoiding some trees, headed back toward the coast. Something hit the right engine, which lost power, knocking the airplane into a steeper bank. I threaded my way between groups of trees, fighting the controls, and struggled from one meadow to another. At last I crossed the beach and turned south toward Piombino Point and the Isle of Elba. I knew that my remaining engine wouldn’t make it, so I started preparing to ditch the airplane close enough to Elba that I could swim ashore. Before long, however, I realized my remaining engine was failing—I’d never make it to Elba now. The coolant temperature was up against the peg, and oil pressure was gone. Slowly, Duckypoo was going down—nothing I did could stop her steady descent.

I was diagonally approaching long swells topped with whitecaps. Though not deliberate, it was the best thing that could have happened: I was making a classic ditching approach to a rough sea. I watched, spellbound, as the whitecaps came closer. In desperation, I kept pulling back on the controls, trying to hold the airplane off as long as possible. Duckypoo started skipping from wave to wave. After about the sixth or seventh one, she plowed into a swell and stood on her nose. The crash was surprisingly gentle but sudden, and I was still fumbling with my seatbelt and parachute harness when I went under with the airplane. I finally was able to kick free and leave the cockpit, and immediately pulled both lanyards on my Mae West. The life jacket inflated. After what seemed an eternity, I popped to the surface.

It was about 10 a.m.—my old hack watch quit as soon as it got wet. The sudden silence was eerie; the only sound was the wind and the waves. The minutes turned into an hour or so, and I began to realize that nobody had seen me go down. I could see the beach, maybe three miles away. But a slanting wind was keeping me out at sea. I tried to swim. It was hard to do in the Mae West and heavy G.I. shoes. I tried to pull off the shoes but couldn’t because my legs had begun to cramp. Soon I could move only my arms, and only in a feeble paddle.

Hours passed. As each wave broke over my head, I began to struggle to keep from drowning. Occasionally I vomited some of the water I swallowed. I remember hearing airplanes, and watched a group of fighter-bombers attacking targets on the coast. Eventually, the wind subsided a bit, and began to blow toward the northeast. Over the course of several more hours, the wind pushed me slowly toward the beach. I began to hear waves breaking onto the sand, so I tried again to paddle.

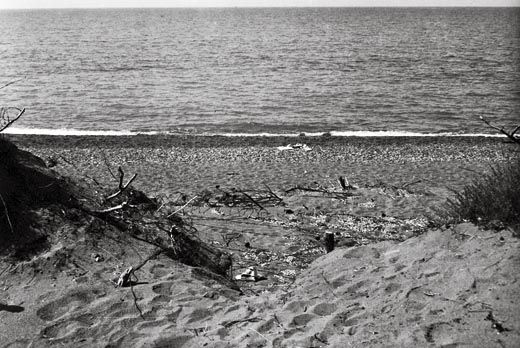

By late afternoon, I had drifted into the breakers, where my progress became agonizingly slow. I half-expected someone to walk onto the beach and pull me ashore. At this point, I didn’t care who it was, German or otherwise—I was totally exhausted. At last, a big wave washed me up on the sand. I was cramped up and face-down, unable to move any part of my body, not even my head. Waves continued to wash over me, but slowly the tide retreated. I tried to move farther up on the beach, but nothing wanted to work—not my arms, not my legs. Eventually, I was able to lift my head, and got my hands and then my arms to move. Finally, I pushed myself onto dry sand.

I remember how warm the sun and sand felt, then nothing more—I must have passed out. I’d been in the water at least ten hours.

When I came to, the sun was down on the horizon. I stumbled up the beach toward some brush, and got caught in a barbed-wire entanglement. It snagged my clothes and tore a deep cut in the palm of my left hand. If there were mines, they were buried deep, because I didn’t trip any. At the first brush pile, I took off my Mae West and buried it. Then I climbed up the six-foot bank and into the deepest brush I could find. The Germans hadn’t found me yet, and I wasn’t going to make their job any easier.

In the brush I found a patch of sunlight and pulled off my socks to dry them. I took out my escape kit and assessed my situation. The kit was a six-inch-square, rubberized-canvas pouch that we carried on every flight. Each kit was numbered. Pilots had to sign them out for each mission. I found a large silk map of Italy, an Italian/English dictionary, a short hacksaw blade, and a small compass with a dot pointing north. Except for the hacksaw, I would use every item to make my escape, especially the compass.

I was some 50 miles behind German lines. To make my escape I planned to walk east, deep into the mountains, and turn myself over to the Italian partisans, or resistance fighters. Ever since September 8, 1943, the date of the Italian armistice with the Allies, these partigiani had become a problem for the Germans and the Fascists. The brutality of the Germans toward villagers they suspected of resistance only bolstered the resolve of the partigiani. The Germans’ horrific massacre of 5,000 Italian soldiers who had surrendered in Greece, just after the armistice, was among the first of many atrocities, including more than 400 massacres of civilians, that proved to the Italians they couldn’t trust the Germans.

Still, we’d been told that the cities along the coast were likely Fascist, and that those Italians wouldn’t hesitate to turn us over to the Germans, who offered rewards for Allied aviators. Years later, during my first trip back to the area, I learned from former partisans that the Germans had been looking for me, and even offered a reward for my capture. They and the Italians thought I’d crash-landed on the coast; they hadn’t known I’d ditched at sea.

I curled up in the brush and went to sleep. When I awoke it was dark. Time to move out. I removed my pilot’s wings and all insignia except my first lieutenant’s bar and buried them. All I would need if I was captured would be proof of rank.

I had moved only a short distance when I encountered a massive complex of trenches, pill boxes, machine gun nests, and earthworks. Oddly, the place was deserted. I learned later that the Germans had built these defenses in anticipation of an Allied coastal invasion and beachhead, similar to that at Anzio. It must have taken me half an hour to work my way through it all.

On the other side I found myself in meadows surrounded by trees. I came to a creek that was pretty deep, so I followed along the bank until I found a narrow masonry bridge. I figured this must be the Cecina River; if so, I was on course into the mountains.

About then, a full moon started to come up. This made it easier to see the terrain but forced me to stop frequently. I had to wait to cross each meadow until a cloud covered the moon, affording me some invisibility. It slowed my progress, but I had little choice.

I came to a double railroad grade, and climbed over it into a patch of woods. Approaching an asphalt road bathed in moonlight, I hunkered down to wait for a cloud. Suddenly I heard footsteps and voices coming from up the road. I buried myself in the brush. With my face covered, I couldn’t see anything, but the sound of hobnail boots told me they were probably German. I held my breath and remained frozen….

Toomey eventually fell in with the italian partisans. They hid him, and kept him constantly on the move, rarely letting him stay with one group for more than a few hours. They ate squash blossoms, cabbages, onions, raw eggs, and very green apples. After four days, the Americans overtook the area, and Toomey returned to his unit and resumed flying.

In 1976, he traveled back to the region and visited Guardistallo, a village he recalled from his time there. He was warmly received by the people, who showed him a bronze plaque bearing the names of 68 villagers whom the Germans had rounded up and machine-gunned on June 29, 1944, in reprisal for hiding Toomey and other American pilots. Twelve of the victims had been partisans, while the rest were innocent men, women, and children. “I feel that the price paid by the Italian people was far more significant than my modest contributions to World War II,” Toomey says today. “I still find it incomprehensible that the German soldiers, presumed human beings, could sink to such levels of moral depravity.”

In July 2000, Toomey returned again, this time with professional divers Bill and Gary Peters. The Peters brothers had heard Toomey’s story and decided to fund a preliminary search for the airplane. In Cecina, the trio met an Italian diver who informed them of six wrecks off the coast, all charted with LORAN coordinates by the Italian government to help fishermen avoid the craft with their nets. He had personally dived on five of them, but none was a P-38. He introduced them to a dive boat captain who took them out to the one charted wreck that remains unidentified. It lies almost four miles offshore in 116 feet of water. The sea had been rough all week, and the brothers were able to dive only once. When they reached the bottom, visibility was three to four feet, and they ran low on air before they could find the wreck. But based on their research, including triangulations of Toomey’s flight path with where he washed up on the beach, and his personal recollections, all feel confident that this wreck is Duckypoo, and share a hope that an aircraft collector will step forward to help tell the final chapter of Toomey’s tale.

Despite his harrowing World War II experiences, David Toomey is still an ardent fan of aviation.