Can we afford to return to the Moon?

We are almost at the end of a year that has seen major changes in our space program.

We are almost at the end of a year that has seen major changes in our space program. We have in hand a report from a “blue ribbon” Presidential committee that concluded that Project Constellation, the architecture NASA had chosen to implement the Vision for Space Exploration, was not affordable at current funding levels but might be accomplished with an increase in the agency’s budget, on the order of an additional $3 billion per year. The committee presented architectural alternatives to Project Constellation, one of which eliminated the Moon in favor of a “flexible path” that allowed human missions to other destinations (e.g., an L-point, an asteroid) beyond low Earth orbit.

I take issue with several points in the Augustine report and have commented on them at length in several previous posts of this blog. But now that the dust has settled and we have a “new direction” for our space program, its two principal deficiencies are evident. First, by discarding the clear strategic direction provided by the VSE, we have entered an era of uncertainty and aimlessness of purpose in our space program. This institutional drift is reflected in nearly daily stories about NASA – new missions studies, new launch vehicles, the endless personal backbiting amongst the space internet cognoscenti. Second, the assertion of the report that return to the Moon is “unaffordable” is simply wrong. How you go to the Moon and what your mission is there determines cost and all the committee looked at were cost models for the existing program and minor variants on it.

I have made both of these points here and elsewhere and many were quick to challenge me to show how we could go back to the Moon under the conditions and assumptions of the Augustine committee. Rather than shut up, I now put up. I have submitted a paper for publication in the Proceedings of Space Manufacturing 14, the conference in late October sponsored by the Space Studies Institute. My co-author Tony Lavoie and I have developed an architecture that returns America to the Moon with a specific mission in an affordable way. Our paper has now been accepted for publication, so I am posting a pre-print of it on my web site and will summarize our findings here.

One of the biggest problems with NASA’s implementation of the VSE was that they never understood why we were going to the Moon. I base this assertion on their own statements, actions and publications. Early workshops were held by the agency to develop a rationale for lunar return. The Exploration Directorate issued a poster showing six “themes” for lunar return, but no one at the agency could state their mission in one sentence. At a Congressional hearing in 2009, the acting administrator of NASA said the he did not understand what “return to the Moon” meant in terms of mission objectives and activities.

The agency took the position that they were merely transportation agents – that it was up to the various “user” communities to decide that activities were to be undertaken on the Moon. As a matter of fact, the Vision itself very specifically laid out what was to be done on the Moon and even how to approach it. The purpose of lunar return is to learn the skills and develop the technologies we need to live on another world. The Vision specifically mentions that one skill we need to acquire is the use of extraterrestrial resources to make both exploration and human presence permanent and sustainable.

NASA ignored this direction. There are many reasons why they did this, but I believe that the main one was they did not know how to create sustainable human presence on the Moon using its resources and were concerned that such a thing might not be possible. But building large rockets is certainly possible – history documented that. So the VSE morphed into a rocket-building program, an Apollo Redux because that’s what the agency (allegedly) knew how to do. The only problem was that we do not live in the Apollo era and the space program no longer gets 7% of the federal budget.

The approach we take in our new architecture is to: 1) define the mission clearly and directly; and 2) design an architecture that accomplishes the mission in small, incremental and cumulative steps. These last three adjectives are important: Steps must be small to be affordable, not only under existing budgetary constraints but also under possible lower budgets that could be necessitated by national economic conditions in the future. The steps should be incremental, meaning that each step adds some asset or capability and must work in tandem with previous equipment and operations. Finally, the steps must interlock such that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. The architecture cumulatively increases features and capabilities with time.

We take as our mission the original Vision for Space Exploration. We go to the Moon to establish a permanent human presence there and a reusable, refuelable, and extensible transportation system to support such presence. Once established, we will have a space faring system that can not only routinely access the Moon, but all other points in cislunar space and beyond, including the L-points and near-Earth asteroids.

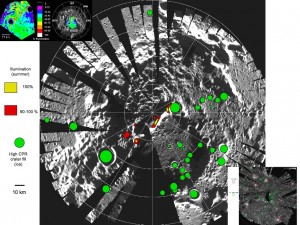

How do we accomplish all this? One of the principal advantages of the Moon as our first goal beyond LEO is that: 1) it has the material and energy resources we need; and 2) it is both close and accessible. This latter set of attributes is more important than you might think. The closeness of the Moon allows us to directly control and operate robots on the lunar surface; the time-lag between action on Earth and execution on the Moon is only a bit over one second. We can operate machines on the Moon in near real-time. Additionally, we can send space vehicles to the Moon at virtually any time. No other space destination is so easily and readily accessible.

The key to making all this work is the use of teleoperated robotic machines. We go to the Moon robotically first and later with people. These robots are controlled by people on the Earth. They prospect for resources, test techniques, evaluate product yields, set up processing plants, and begin harvesting lunar resources almost immediately. The extracted products are cached on the surface for future use. The entire lunar outpost is set-up and made operational by these robotic machines.

Our architecture is designed so that time is a free variable. We make constant, steady progress toward our goal; in fiscally lean times, we go slower, but we can accelerate the schedule if more money is available. Making individual steps small and incremental permits this approach – we are not waiting for the development or advent of some “magic carpet” piece of equipment to fill a major hole in our plan.

So what’s the bottom line? Our plan creates a fully functional, operating lunar resource outpost capable of manufacturing 150 metric tonnes of water per year. In addition, we develop a reusable space faring system, one fueled by lunar propellant and expandable to support missions to the planets and destinations throughout cislunar space. We do all of this under the budget guidelines provided to the Augustine committee by NASA; total aggregate funding for this program is less than $88 billion (real-year dollars), with peak funding of $7.1 B in Year 11. Although schedule is flexible, we achieve our primary mission goals by the end of year 16. We have had our assumptions, mass estimates and costing examined, reviewed and validated by a variety of space experts, including the Engineering Directorate Mission Analysis Group at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. This program architecture does what Project Constellation did not: it returns America to the Moon with a legacy of real and permanent space faring infrastructure.

In contrast to the current drift of our space program, the original Vision for Space Exploration set a strategic direction and path that made sense, giving us an expanding sphere of human reach beyond low Earth orbit. The idea that America cannot afford space is ludicrous – we have the world’s largest economy and the amount we spend on space is now less than one-half of one percent of the federal budget. But whatever we spend on space, we should expect to get something in return. A lunar outpost and space transportation system gives us a return on our investment; a program of one-off, stunt missions does not.

The path forward into the future is still open to us.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/blog_headshot_spudis-300x300.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/blog_headshot_spudis-300x300.jpg)