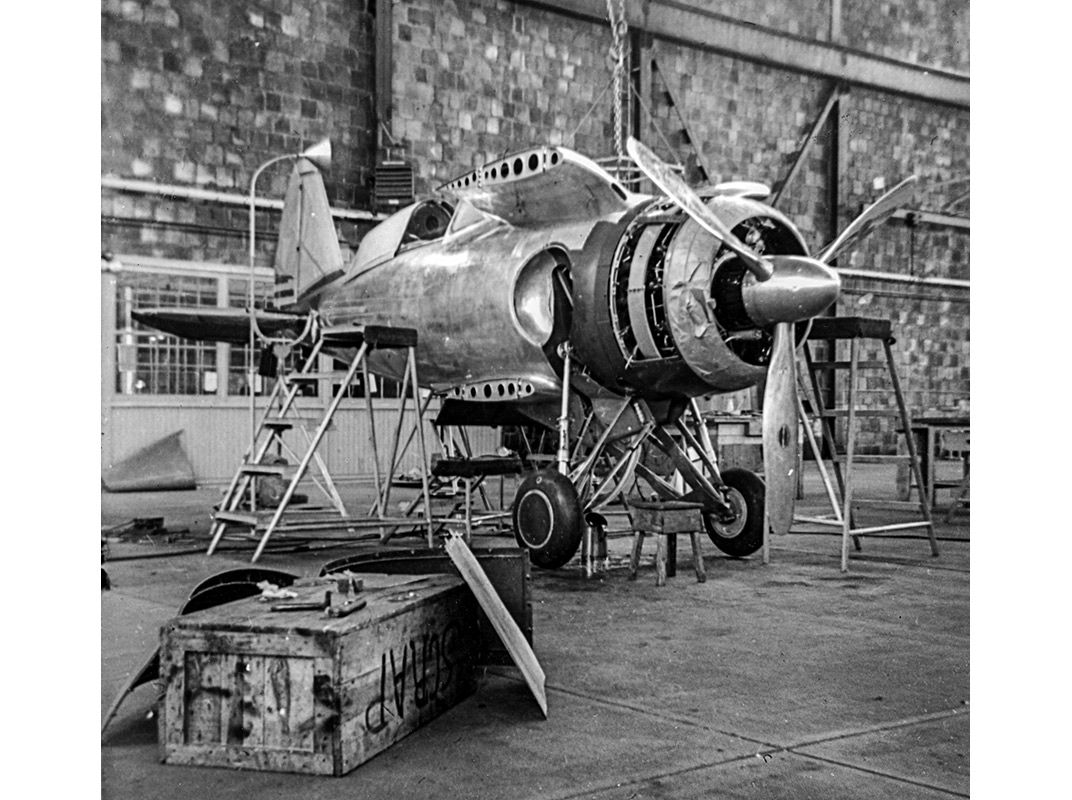

Cancelled: The Gregor FDB-1

One pilot called the Canadian biplane “chubby in a vicious way.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/51/6e/516e152d-6b20-47df-a89d-511bf3c03f97/main-gregor.jpg)

“They’ll start the war with monoplanes but finish it with biplanes.” So predicted aeronautical engineer Michael Gregor, who persuaded the Canadian Car & Foundry Company Limited (Can-Car) of Montreal to hire him to design and build a highly maneuverable biplane fighter at its Fort William, Ontario plant. It would have to compete with the likes of Hurricanes and Helldivers. Can-Car’s general manager, Leonard Peto, was evidently impressed. In 1940, he told the Montrealer magazine he thought the new aircraft “would find a heavy market in Britain and France.”

Can-Car was founded in 1909 and built railway cars and the occasional minesweeping ship until falling on hard times in the 1920s. A 1935 tax deal with the Fort William city council rejuvenated the company as an aircraft builder, specifically of the Grumman G23 biplane fighters, most of which went to Spanish Nationalist Forces and the Royal Canadian Air Force, which called it the Goblin. Over the years, Can-Car also manufactured Hawker Hurricanes, Curtiss Helldivers, and North American AT-6s under license. In 1937, the company sought its own engineering and design capability, and Gregor’s résumé looked good: The Russian-born engineer had helped design Brunner-Winkle’s Bird biplanes; had served as chief engineer at Seversky Aircraft Corporation, working on the SEV-3 Sport Amphibian; and had run the Gregor Aircraft Corporation at Roosevelt Field in New York, where he prototyped the GR-1 Sportplane. Can-Car hired him as chief aeronautical engineer.

Gregor’s convincing pitch included marrying some of the newest aircraft technologies, like stressed-skin construction, bubble canopy, streamlining, and retractable gear, with the proven dogfighting agility of the biplane. The most striking features of his elegant design were the gull shape of the upper wing, the teardrop canopy, the flush gear retraction, and smooth fairings all around. Gregor chose the 750-horsepower Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp engine and aimed for a 1,200-hp option. Dubbed the FDB-1 (for Fighter-Dive Bomber), it first flew in April 1939.

In enticing the Royal Canadian Air Force to test it, Canada’s Department of Transport cited the report from trials that Can-Car had run: “[T]he aircraft has been spun at least twice to complete eight full turns. Also, the tail parachute has been tested in the air for correct functioning and ejection.” The parachute was to be deployed if the FDB-1 entered a non-recoverable spin (a nose-down attitude would restore control-surface function). The Can-Car report added “the terminal velocity dive test was performed from 23,000 feet, attaining an indicated air speed of 472 mph…all acrobatic manoeuvres can be performed smoothly and satisfactorily.”

Impressed, RCAF Flight Lieutenant L.E. Wray made a test hop on May 10. Apart from an alarming canopy vibration during loops, he was taken by its snappy handling. Performance, not so much. Wray recorded an initial climb rate of 2,800 feet per minute (Can-Car had predicted 3,400) and 402 mph in the dive (against Can-Car’s 472 mph), with an easy 7-G pullout. The gull-wing blinded him on landing, but “it has maneuverability to the extreme,” he wrote. “Below 15,000 feet, a contemporary low-wing monoplane or single seater, despite superior performance, could not successfully engage the Gregor singly.”

But in performance, the FDB-1 wasn’t beating monoplane fighters by much, and this was 1939, when Can-Car was gearing up its Hurricane production lines for war. Without clearly superior performance, the RCAF wasn’t convinced that regression to biplane design was the way to go.

The company didn’t give up, however. The sales team got Mexico interested in manufacturing the biplane under license in 1940, but the Canadian government inexplicably nixed its export. The following year, Can-Car flew a demonstration at Roosevelt Field for another potential foreign client. The pilot was Fred Smith of Canadian Colonial Airways, who called the FDB-1 “chubby in a vicious way.” Smith too had been delighted with its “feather-touch” handling. Following the demo, he reported a tentative offer of “a colonelcy in a South American nation’s air force if I’d train a squadron in these aircraft.” Someone was impressed, but not enough to place an order.

Gregor’s fighter languished in a Dorval hangar in Quebec until the mid-1940s, when it was destroyed by a fire. Gregor’s patience seems to have run out long before that: He quit Can-Car shortly after RCAF interest had evaporated, moving back to the United States and eventually landing a job with Chase Aircraft Company, which built “assault gliders,” a term only the military could utter with a straight face.