POWs on The Day They Learned the War Was Won

Who were the airmen in John Swope’s famous photograph of the Omori prison camp?

:focal(874x1066:875x1067)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f9/60/f9601969-1f93-41fd-8ccc-e62d0239e28f/34d_aug2020_openercorygraffmainpowomori_live.jpg)

No one makes an entrance like the Americans. One of the first indications that they were closing in was the crash of a heavy wooden crate of Cashmere Bouquet soap plunging through the roof of the Omori prison barracks, missing Army Air Forces Major Robert F. Goldsworthy by three feet. “I thought, what a hell of a thing, to live through prison life only to get killed by a case of soap,” he wrote in 2000, in a comment posted to a B-29 website.

Until a few weeks before, there had been little hope among the approximately 600 prisoners at the Omori main camp. On the manmade prison island in Tokyo Bay, rumors were nearly as thick as the lice and the rats. Most of the prisoners speculated that when the Americans got too close, the guards would gather them together and gun them down. And by the summer of 1945, there was little doubt that the Americans were now very, very close.

From their barracks, the prisoners had seen the night skies glow from fires in Yokohama and Tokyo as they burned from massive B-29 bomber raids. Later they caught glimpses of smaller airplanes, launched from U.S. aircraft carriers, shuttling through angry puffs of anti-aircraft fire to pummel nearby airfields, port facilities, and storehouses. Their comrades were tantalizingly near.

Click on the dots to identify some of the POWs in Swope’s photo. (Apple News readers can click on this larger interactive version.)

Some of the prisoners interned at Omori were already “dead”—at least, no one outside the prison walls knew they were alive. The Japanese classified the captured sailors and airmen as “unarmed belligerents,” and they were held without rights or privileges. The Red Cross, the U.S. government, and the men’s own families had no information about them.

Omori’s population included prisoners who the Japanese viewed as the most troublesome, valuable, or notable, many of whom had been transferred from a nearby secret high-intensity interrogation camp run by the Japanese navy. After the enemy had wrung as much information as they could from their captives through torture and abuse, the men were sent to established labor camps, like Omori.

As a result, an Omori roll call sounded like a Who’s Who of the war in the Pacific. At one time or another, the camp was home to Marine Corps ace Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, former Olympic runner and Army bombardier Louis Zamperini (the subject of Laura Hillenbrand’s 2010 book Unbroken), and Richard “Killer” O’Kane, the most successful submarine commander of the war.

The treatment at the camp was horrific. The Japanese demanded labor in exchange for meager rations, so the able-bodied men were sent to work at nearby docks and warehouses. They did what they could to sabotage the work instead of supplying meaningful labor. Beatings, sickness, and barely edible food led to the death of many of Omori’s prisoners.

But things changed suddenly on August 15, 1945. After the Japanese emperor’s speech announcing surrender, the forced work details suddenly ceased. Many of the guards abandoned their posts, and those who were left passed out clothes, vitamins, toilet paper, and more food than the startled captives had ever seen before. “It seems as if the Japanese were trying in a few days of kindness to make up for the years of deprivation and cruelty,” Ernest Norquist, a Bataan Death March survivor, wrote in his postwar memoir, Our Paradise: A GI’s War Diary.

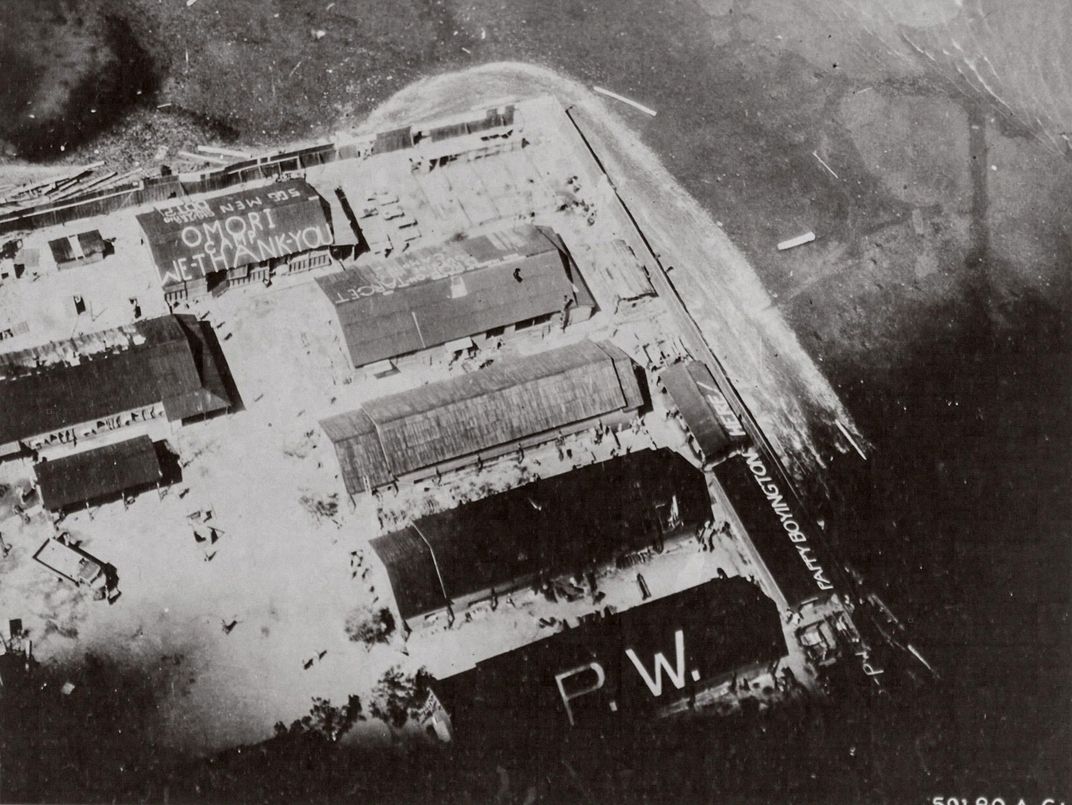

Now the American carrier aircraft roared overhead unimpeded, so close the prisoners could see the pilots’ faces. The prisoners took to writing messages on the barracks roofs using Japanese tooth powder mixed with water, including large “P.W.”s (prisoner of war), “Pappy Boyington Here!” and “Candy, Food, Home, Thanx.” Other men made flags from bedsheets and colored pencils. A Corsair pilot dropped half a pack of cigarettes with a note wrapped around it, which read, “Hang on! It won’t be long now!”

Another message was added to the top of the barracks after a B-29 Superfortress lumbered over, dropping loads of medicine, food, clothes, toothbrushes, razors, gum, and the big box of soap that nearly killed Bob Goldsworthy when its parachute-rigged bundle broke apart in midair. The new directive on the roof stated: “Drop-Out-Side Thank-You.”

By the time American ships advanced into Tokyo Bay on August 29, the prisoners were delirious with excitement. Their death sentence, it seemed, had been lifted. That afternoon, a group of landing craft began churning toward the shore with an Avenger torpedo bomber from the USS Cowpens guiding them straight toward the camp.

The first boat that came close to the enemy’s shoreline was filled with top brass, doctors, and nervous sailors with very itchy trigger fingers. The craft also carried a Navy photographer named John Swope. The scene in front of him was pandemonium. “We finally spotted the moving figures on a pier jutting out to the bay,” he wrote his wife. “We came closer—they were screaming and yelling and waving their arms, their shirts, and an American flag. Some wore no clothing at all, some had G-strings, and others had on the remnants of what they were captured in, and a few had on new clothes that had been dropped on them by B-29s the last few days. Some started to swim for our boat and were told to go back; the others kept waving and shouting and we waved and shouted back and tears came to my eyes.”

Swope was able to get only a few shots before the boat came ashore and he was mobbed. “[We] were immediately besieged by a hundred clasping hands and arms. They continued to cheer and yell and shake our hands and clap us on the back and fall on us in tear-soaked embraces. They asked us a million questions. They told us millions of things about themselves, and all the talk jumbled into a great din of welcome, with no one hearing anyone.” Swope’s 144-page letter of the experience, written to his wife, actress Dorothy McGuire, was later republished in a book by Carolyn Peter titled, A Letter From Japan: The Photographs of John Swope.

Over the years, historians and biographers have searched the famous photo for individuals, but the identities of all have never been revealed in a single report. Their stories of survival and capture are a fascinating narrative of the Pacific war, ranging from its first day to the very last.

Private Milton L. McMullen was assigned to the B-17s of the 19th Bomb Group at Clark Field in the Philippines. When the Japanese attacked, on the same day as Pearl Harbor, McMullen was injured by shrapnel from exploding bombs. He avoided the Bataan Death March when the locals secreted him away, nursing him back to health. Three months later, the Japanese caught up with him.

On December 10, 1941, Captain Colin Kelly’s B-17C flew over the Philippines, looking for enemy ships. After bombing a light cruiser and a destroyer, the B-17 crew was attacked by Zero fighters. Kelly ordered his men to bail out of their damaged aircraft. Private Robert E. Altman, the radioman and “tub gunner” on Kelly’s burning airplane, was one of the men who jumped.

When the bomber exploded, Kelly became one of America’s first heroes of the war. Altman, who had been wounded in the attack, was captured in the subsequent seizure of the Philippines. At the time of Swope’s photo, he had been a prisoner for more than 40 months.

Many miles away and a few years later, American carrier aircraft were working over Japanese-held outposts in the Pacific. The target for the USS Hornet ’s aircraft that day was Chichi Jima, which was dreaded by the aviators. The harbor was surrounded by hills studded with anti-aircraft guns; the pilots called the harbor “the punch bowl,” and there was only one path in and out. In his book Dauntless Helldivers, Harold Buell relates his feelings about the island. “Chichi Jima was a tough, dirty target that always scared the hell out of me and left me feeling like I hadn’t accomplished anything except to stay alive when I got safely outside the bowl again.”

On June 15, 1944, Lieutenant Daniel Galvin flew his Curtiss SB2C-1C Helldiver into the bowl on a bombing run, but no one saw him come out. The Hornet ’s aircraft action report states, “Lt. Galvin was apparently hit by [anti-aircraft fire] as he was last seen in his dive.” Galvin and his gunner, Airman Oscar Long, spent the next 14 months as prisoners of the Japanese.

On April 7, 1945, a Boeing B-29 named City of Muncie was rammed head-on by a Japanese fighter over Nagoya. The airplane’s left wing ripped away as it rolled over on its back and spun down in flames. Three of the 10-man crew were captured, among them Sergeant William Price. He related years later, “[We] were captured as soon as we hit the ground.” His two surviving companions, Lieutenant Melvin L. “Smoke” Greene and Sergeant Leroy Siegel, were also interned at Omori.

Lieutenant Gordon Scott was putting on his own fireworks show on July 4, 1945. He was blasting Japanese floatplanes northeast of Tokyo when the engine on his North American P-51D, named Sparkin’ Eyes, suddenly spewed gallons of oil onto his windscreen and then quit cold. He had just enough time to jettison the canopy and put both hands on the gunsight to protect his face before the Mustang’s air scoop dug into the waters of Lake Kasumigaura at 90 miles an hour.

Civilians pulled Scott from the water and beat him badly, cut him with rice knives, and seemed determined to kill him. Japanese soldiers pulled him from the enraged mob, and shoved Scott into a cage filled with other American airmen, some of whom appeared to have been there for years. Even so, he thought, “My God, I have it made.”

On July 28, 1945, while attacking a battleship in Kure Harbor, a Consolidated B-24J named Lonesome Lady was badly hit. Pilot Lieutenant Thomas Cartwright struggled to control the aircraft, but it was hopeless. Seven of the 10-man crew were captured soon after bailout and transported to a nearby city.

By early August, Cartwright was singled out and moved to an interrogation center near Tokyo. He later wrote, “I felt a bit sorry for myself.” On August 6, when the atomic bomb leveled the city of Hiroshima, Cartright’s six crewmates and six more U.S. airmen captured in the raid were still there. The military police headquarters building in which the prisoners were housed was just 400 yards from ground zero; all died from the resulting blast.

One of the photographs Swope shot of the Omori prisoners on the shoreline appeared in hundreds of American newspapers in 1945 and became the cover of U.S. Camera’s Victory Volume in 1946. The image of the prisoners waving three flags in a near-riot of jubilation shows more than 30 men—a mere fraction of those interned at Omori.