Those Safety Instructions in Your Airplane Seat Pocket? Nobody Understands Them.

An FAA survey found comprehension levels as low as 18 percent.

:focal(246x182:247x183)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/af/53/af5337f4-0bba-4935-93f8-b68c34ddbcf3/no_luggage.jpg)

How hard is it for novice fliers to understand the information on airline safety briefing cards? It’s almost impossible, according to a paper presented at the FAA’s International Fire & Cabin Safety Research Conference in December 2013. The survey, conducted by the FAA’s David Weed, indicated that passengers had a hard time correctly interpreting the information presented on 41 state-of-the-art briefing cards. Comprehension scores ranged from a barely adequate 70 percent to a dismal 18 percent.

The correct reading of the extremely busy pictograph at the top of this page would be something like, “When using the emergency evacuation slide, passengers should leave behind their luggage (to exit more quickly) and remove high heels (which could puncture the exit slide).” But some people surveyed thought it meant that all clothing should be removed before exiting. And only 26 percent of respondents interpreted the image correctly.

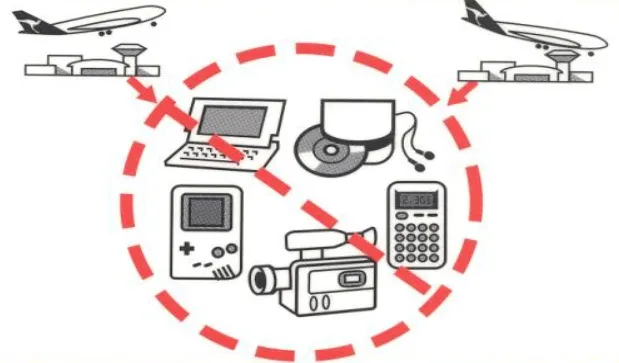

The correct reading of the card below is “These items may not be used during takeoff and landing.” Wrong answers from the survey respondents included the opposite meaning, “use these items only during takeoff and landing,” and “no things on airplane.”

The study concludes: “Results are consistent with the previous reports that individual details of the briefing cards are correctly interpreted more often than the briefing card as a whole. Recommendations based on the results of this study include a redesign of briefing cards by non-cabin safety experts, as the novice flying public were not able to accurately interpret the information presented.”

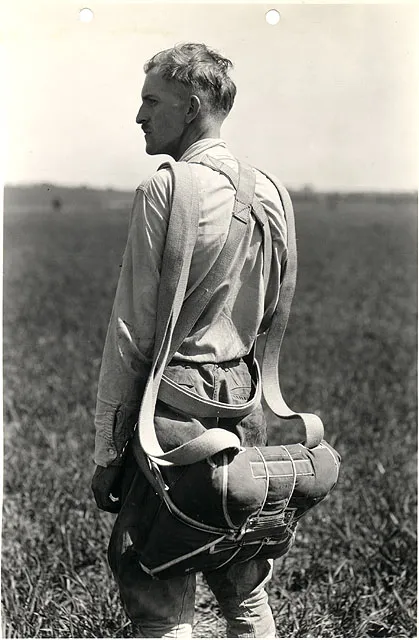

That got us wondering what the first passenger safety briefings were like. “The first pre-flight safety information by airline crews would have been during the airmail days of the 1920s,” says Daniel L. Rust, assistant director at the Center for Transportation Studies at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. “Before climbing into the open cockpit, the pilot would help his passenger strap on a parachute and tell him or her how to use it in case of emergency.”

Safety cards have been in use since the late 1920s, write Eric Ericson and Johan Pihl in Design for Impact: Fifty Years of Airline Safety Cards. But at first they were strictly text-based, and they rarely showed the location of emergency exits. (The authors note that they weren’t able to determine when safety cards were first introduced, or whose idea it was.)

By the 1940s, “the idea of flying was still quite terrifying for many travellers,” write Ericson and Pihl, “[so] one of the aims of safety cards...was to allay such fear. Slogans such as ‘life vests are fashionable and quite handsomely tailored,’ [and] ‘no wet feet for you,’ were often accompanied by comic illustrations.”

In the early 1960s, safety cards became more complex, adding depictions of oxygen systems, flotation devices, and location of exits. In order to save money, many airlines used just one card showing the floor plan—with emergency exits highlighted—of every type of aircraft in their fleet. These “fleet cards” were banned in 1967; the FAA now requires that safety cards outlining emergency evacuation procedures describe only the specific type of aircraft on which they are carried.

Meanwhile, passengers have paid less and less attention to these cards over time. As a 1991 FAA bulletin noted, “It would be desirable to have every airline passenger highly motivated; however, motivating people, even when their own personal safety is involved, is not easy.” And even though pre-takeoff safety information is often given these days by a crewmember or a video, safety cards are still required.