Aviation Pranks, Circa 1910

If you wanted to spice up your lodge meeting at the turn of the 20th Century, the DeMoulin brothers had some suggestions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/b3/c0b39be4-c54f-48a3-b731-0bdbda3e852d/whizbangaeroplane-large.jpg)

Looking for something wonderful to read? We suggest Julia Suits’ book The Extraordinary Catalog of Peculiar Inventions (Perigee, 2011), an offbeat look at the catalogs of the DeMoulin Brothers, an Illinois company that produced prank devices for fraternal lodges around the turn of the 20th century. Suits explains:

As population centers and wayward burgs popped up on the prairie, ridge, and shore, so did lodges of fraternal orders like the Odd Fellows, Masons, Knights of Pythias, Woodmen, and so forth. These lodges were central to the economic and social well-being of their communities. But their success depended on membership. Thus, it made sense for lodges to offer something to keep members looking forward to meetings.

In 1892, when fraternal membership began to surge, competition among lodges to attract and keep members intensified. It didn’t take long for Ed DeMoulin to realize this. A witty, grown-up whiz kid and inventor, he set to work to “amp up the action” at his local lodge in Greenville. Thus, at the intersection of two historic eras—the Age of Invention and the Golden Age of Fraternity—the DeMoulin Brothers Company was born.

Ed DeMoulin was himself a member of the Woodmen Foresters fraternal order, whose meetings were so dull that members often failed to show up, much less pay dues. To spice things up, Ed designed his first prank device, the Moulten Lead Test. Confronted with what appeared to be a pot of boiling lead, lodge candidates would be asked to plunge their hands into the pot to prove their bravery. (The pot actually contained cold water.) Lodge brethren got a good laugh at the candidates’ expense, and the lodge prospered.

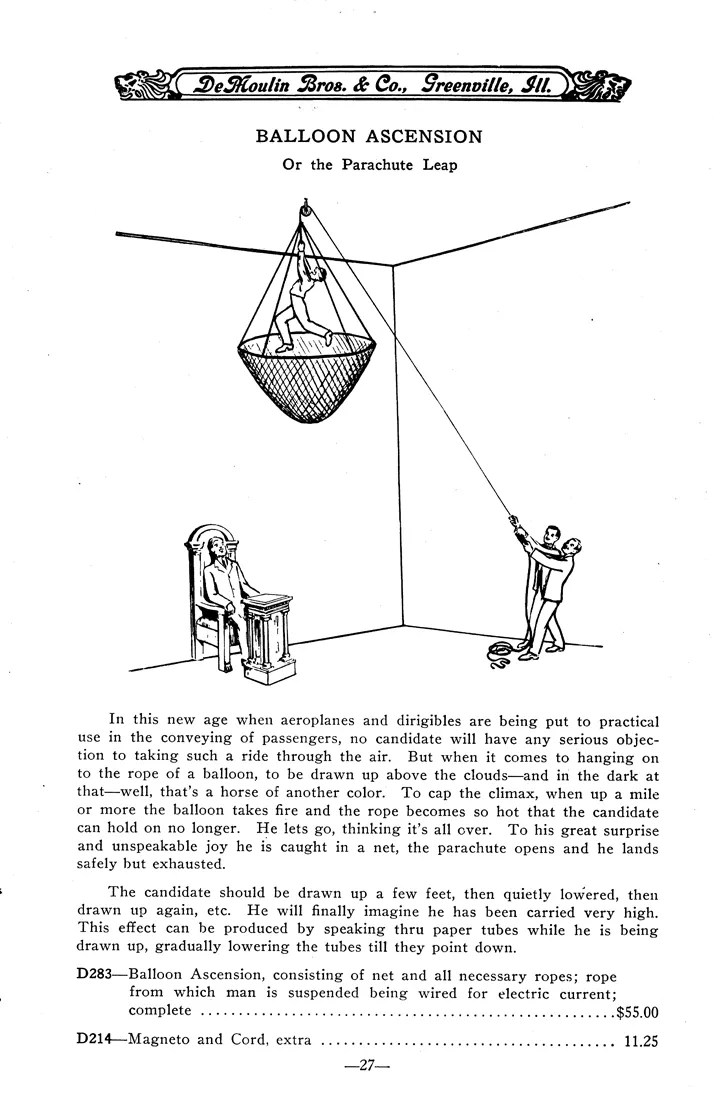

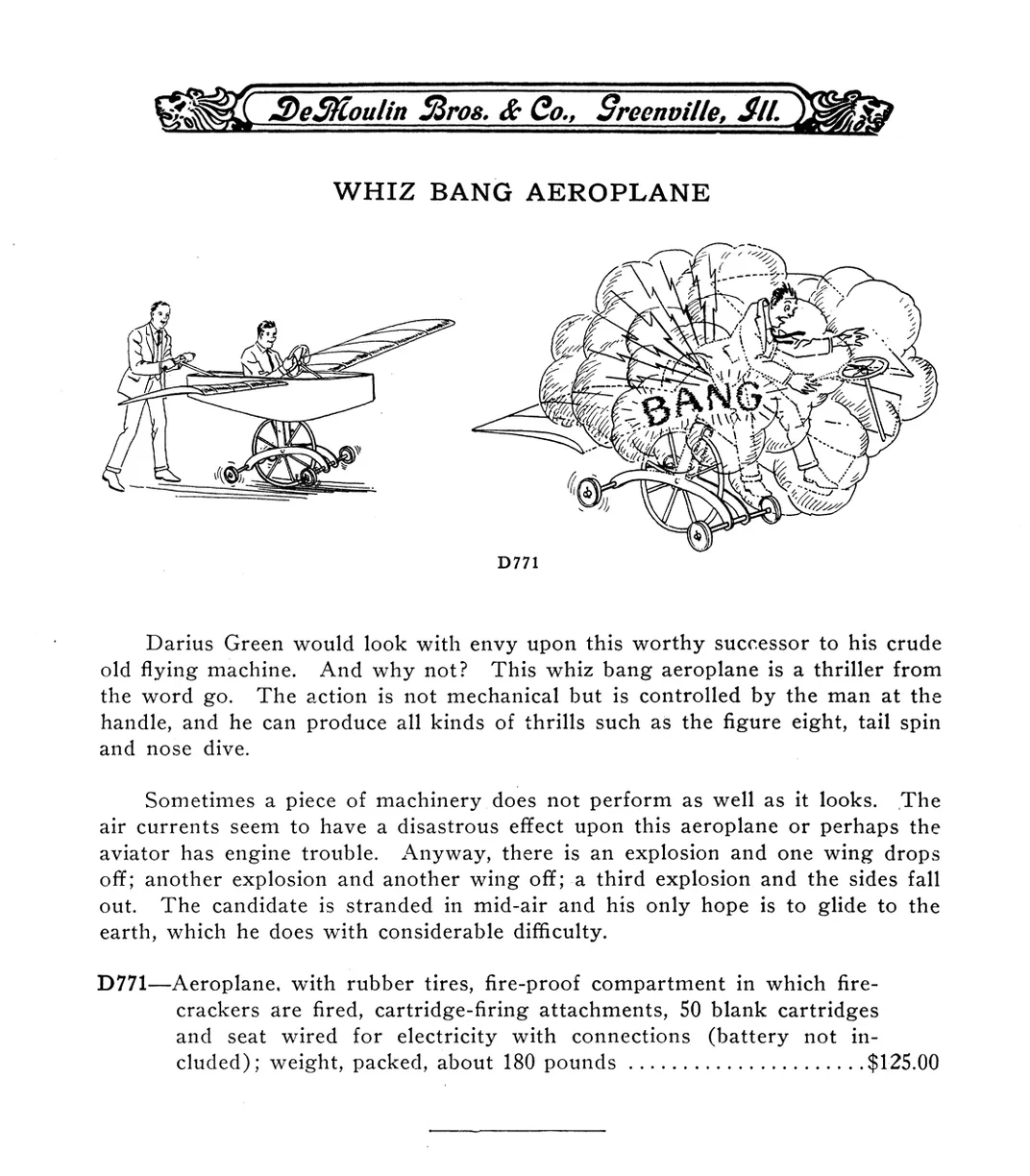

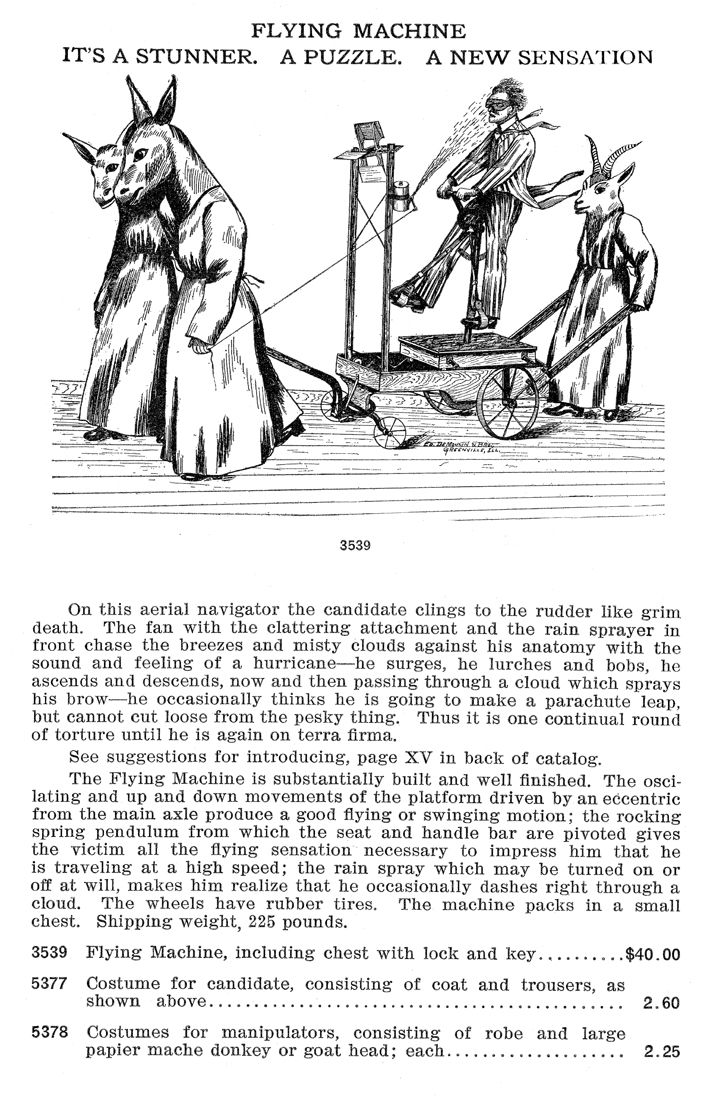

The catalogs included everything from cigar-smoking camels and human centipedes to fake guillotines and electric carpets. As this was the age of the Wright brothers, it comes as no surprise that some of the pranks involved flying machines, although the contraptions were more like something Darius Green, hero of a popular 19th-century poem, would have dreamed up.

The DeMoulin brothers had to take out a $90 bank loan to pay for postage on their first catalog in 1895; they were rewarded with orders totaling $1,600. By 1915, writes Suits, “the equivalent of two railroad carloads of catalogs was shipped out each year. When you consider that the prank catalogs made up just a small percentage of this amount, and that no one other than the highest-ranked officers laid eyes on them, you get a sense of how rare and elusive they were even then. The prank catalogs were published for only thirty-odd years. As quickly as they materialized—they vanished. America had sunk into the Great Depression. Many lodges failed and were supplanted by other forms of social bonding and entertainment.”

Images and text reprinted with the permission of the author.