Champions of the World

With 56 test launches, a Georgia high school team had the data to win big.

:focal(2231x996:2232x997)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/34/aa/34aaff1d-8559-4466-8da4-8da6e9abab14/01k_on2018_rocketcontest2018-4_41457007394_live.jpg)

By the time they got to the International Rocketry Challenge at the Farnborough International Air Show in England last July, the four students from Creekview High School in Canton, Georgia, knew precisely what their rocket could do. They had the data.

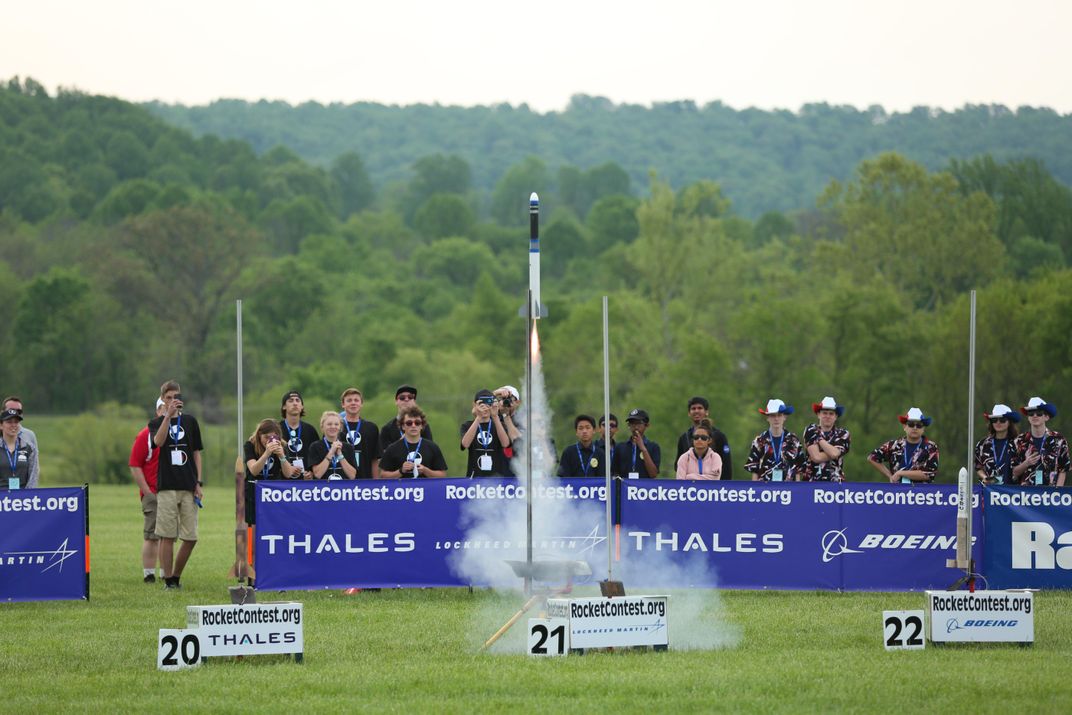

Before they could make it to Farnborough, though, they had to win the national competition in The Plains, Virginia, 50 miles from Washington, D.C., where their rocket, according to contest rules, carried two raw eggs to an altitude of 800 feet and returned them safely to Earth within 41 to 43 seconds of liftoff. Of the 100 teams competing from 28 states and the District of Columbia on that May day, the Creekview four—Brayden Dodge, Warren Teachworth, Kennedy Hugo, and Aiden McChesney—came closest to the altitude and duration targets. “I thought we might be in the top 10,” says Dodge. “When they announced 2nd place, we quietly high-fived each other. We wanted to be respectful to the 2nd-place team. We didn’t start cheering till our names were announced.”

Dodge, now a freshman at Auburn University, credits two aspects of their design for the victory. “We had the smallest fins in the competition,” he says. “And we found a motor we could trust. It’s got to be the smaller things that set your rocket apart,” he continues, “because all the rockets have to meet the same basic requirement.” (Rockets could not be heavier than 650 grams—about a pound and a half; had to have two body tubes of differing, prescribed diameters, and had to be at least 25.6 inches long.)

Creekview science teacher and rocketry coach Tim Smyrl says that because the U.S. teams had won the world competition each of the past three years, the students were really feeling the pressure for the 2018 contest. Smyrl coached the U.S. team that went to the internationals in 2014—and lost. “Yep. The last time we didn’t win was us,” laughs Smyrl, “so we were really, really worried about being the bookends.”

Smyrl seems to be one of those teachers so crazy about his subject that those around him naturally love it too, the science teacher who makes everybody in the class want to be a scientist. Maybe a rocket scientist. As he talks about the preparations for the rocketry challenge, he sounds more amused than exasperated by the choppy air that so bedeviled test and qualification launches that it kept some of the teams in the school’s aerospace club from qualifying.

“The kids would either get hit by a strong thermal or they would end up in dead air when we expected thermal activity,” he says. The club used Creekview’s athletic fields as rocket testing grounds. “We’d be at 801 feet and all the sudden we’d be at 50 seconds because we got nailed by a thermal. Then we’d switch chutes and we’d get to 797 feet, and we’d hit the ground at 31 seconds. Other times, it looked like the rocket was floating. The kids would say, ‘It’s not falling.’ Their eyesight is better than mine, so looking up, I’d just hear, ‘Noooooo!!’ ”

“We made adjustments,” says Dodge, “like delaying chute deployment.” Increasing the time between engine cut off and an open chute shortened the distance the returning payload had to travel through unpredictable thermal activity.

At the international contest, teams were judged not only on their rocket’s performance but also on their presentation of data. One of the judges, former NASA astronaut Don McMonagle, a Raytheon manager of the Ranger Generation Next program, which supports launches of rockets way bigger than the ones competing at the Farnborough event, was impressed by how the teams described their data. “Part of being effective as an engineer is being able to communicate and organize your presentation,” he says. “Several of the teams listed cost as one of the drivers in their decision making, which is a very practical thing to do so early in their careers—to understand that cost would be a design constraint.”

That trustworthy rocket motor that Dodge mentioned, for instance, cost them only $7 a launch. They went to Farnborough with 56 test launches behind them. That gave them enough data to know that the air temperature in Farnborough on the day of the world competition would require them to add just a little weight to their rocket. That’s why the 2018 world champion rocket reached its altitude and landed with a bit of extra payload: about an ounce of Crayola modeling clay shoved inside its nose cone. Hurry. Registration for the 2019 contest is open now and closes December 1.