Sub Hunts in a Seaplane

On cold war missions, in any weather, Martin Marlins prowled the globe.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/7c/f27ccb9b-1024-4295-9989-1b4b2bee83ec/04d-p-t_dj2017_opener_live.jpg)

In the early 1950s, while fighting in Korea was heating up the cold war, the U.S. Navy faced a growing threat to its surface fleet from burgeoning numbers of Soviet submarines, designed to sink American warships and break any blockade of the Soviet coast. These diesel-electric boats could snorkel at periscope depth to charge their batteries, yet run silent and deep when they needed to escape detection.

To counter these threats, the Navy developed an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) doctrine based on three technologies: seafloor acoustic sensor networks guarding oceanic choke points, attack submarines with the latest sonar gear, and aircraft. From Korea through the Vietnam years, the Glenn L. Martin Company’s Marlin flying boat was one of the tines in the Navy’s anti-submarine warfare trident.

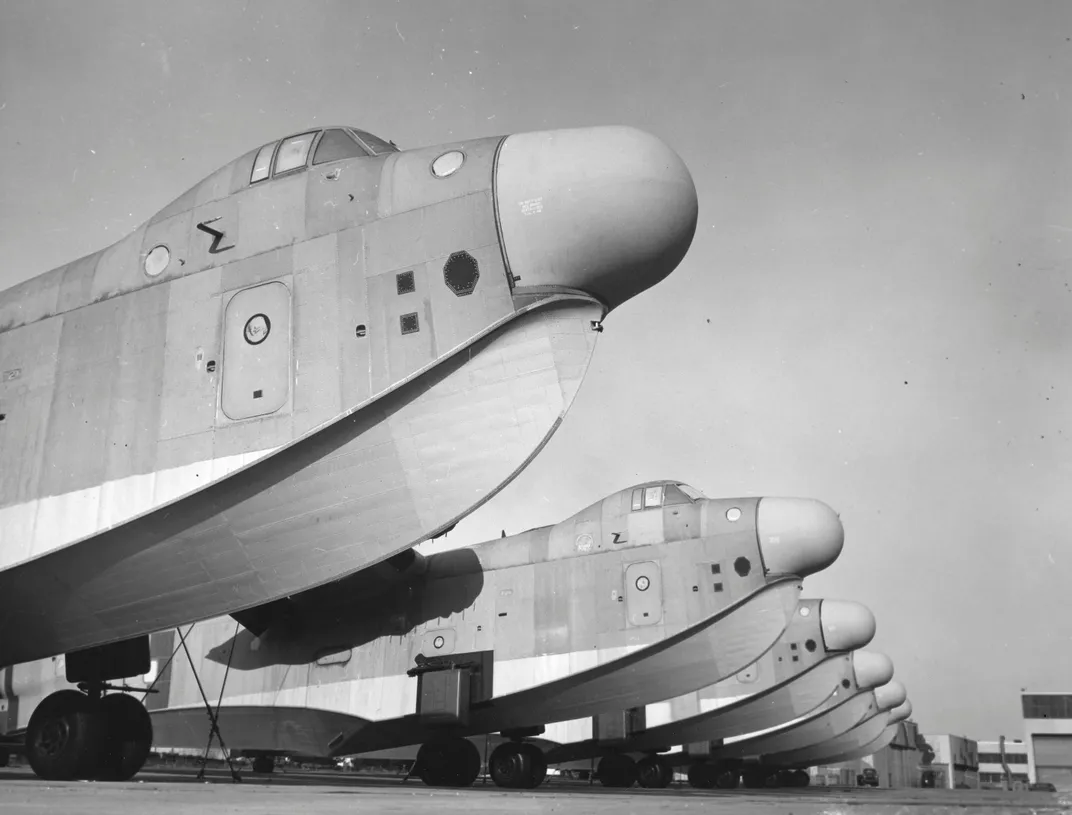

Martin’s design of the P5M Marlin emerged directly from the Navy’s rich seaplane experience in World War II’s Pacific theater. The company’s twin-engine PBM Mariner had been a stalwart of wartime reconnaissance, but by 1945 its limited sensor capacity was not sufficient. A much improved evolution of the Mariner, the XP5M-1 prototype first flew in May 1948. It sported a gull wing to keep its engines above the sea spray and an extended aft hull to reduce porpoising during takeoff and landing. The initial production version entered Navy service in 1952 as the P5M-1 (P for patrol, 5th in the series, M for Martin).

Compared to other aircraft that entered service during the early years of the cold war, the Marlin was an anachronism. At a time when early jet fighters were going supersonic, the Marlin’s top speed was 251 mph, and it cruised at 150 mph on two Wright R-3350 turbo-compound radials. And the Marlin was a true flying boat: To get it ashore, crews had to attach a set of wheels as berthing gear.

Production aircraft were equipped with a powerful search radar in the nose and magnetic detection gear in the tail. The Navy didn’t expect Soviet subs to fight it out on the surface of the sea. Instead, the Marlin would attack with depth bombs and homing torpedoes. Designers had placed a weapons bay in the nacelle behind each engine. Together the two bays could pack 8,000 pounds of bombs, torpedoes, and depth charges. By the late ’50s, the Marlin was also carrying high-velocity aircraft rockets (HVARs) on underwing pylons. Against surface targets, Marlin crews hoped the rockets would keep enemy gunners’ heads down long enough for them to complete a bomb or torpedo run.

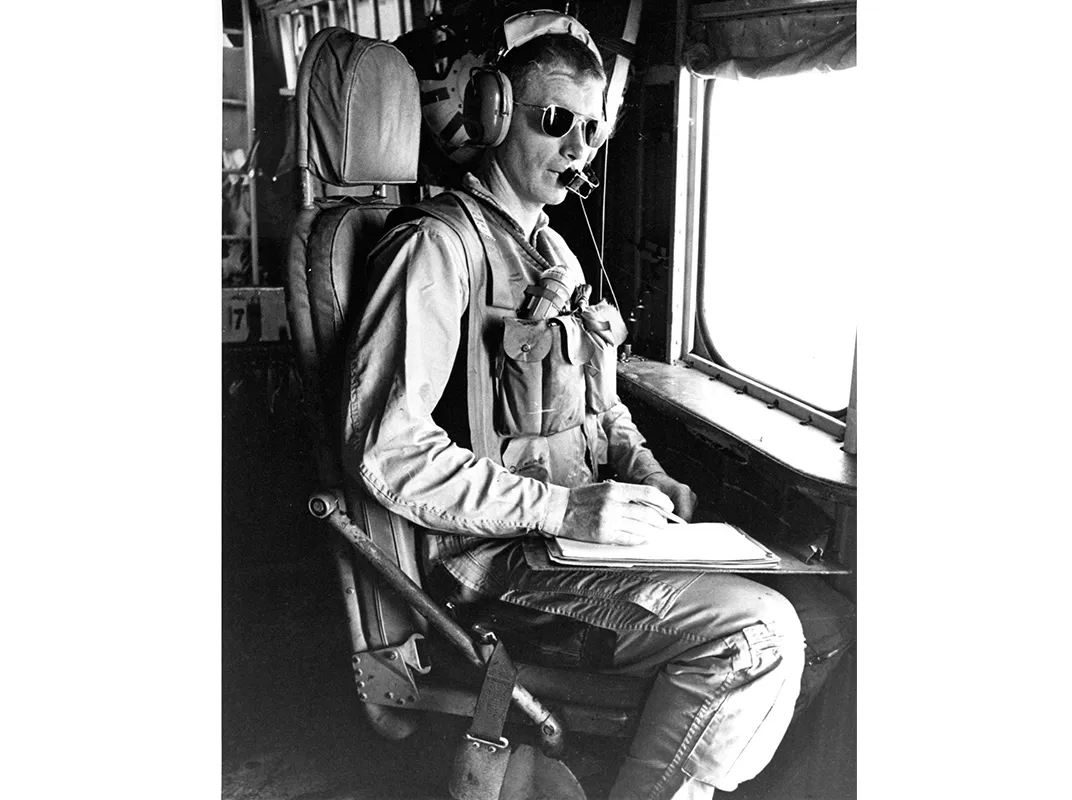

A typical Marlin crew consisted of 11 personnel: two pilots, a pilot-navigator, a radar operator, an ordnanceman, an airplane captain (mechanic) and assistant, a radio/panel operator, a pair of acoustic sensor operators, and an aft observer. Later, a tactical coordinator was added.

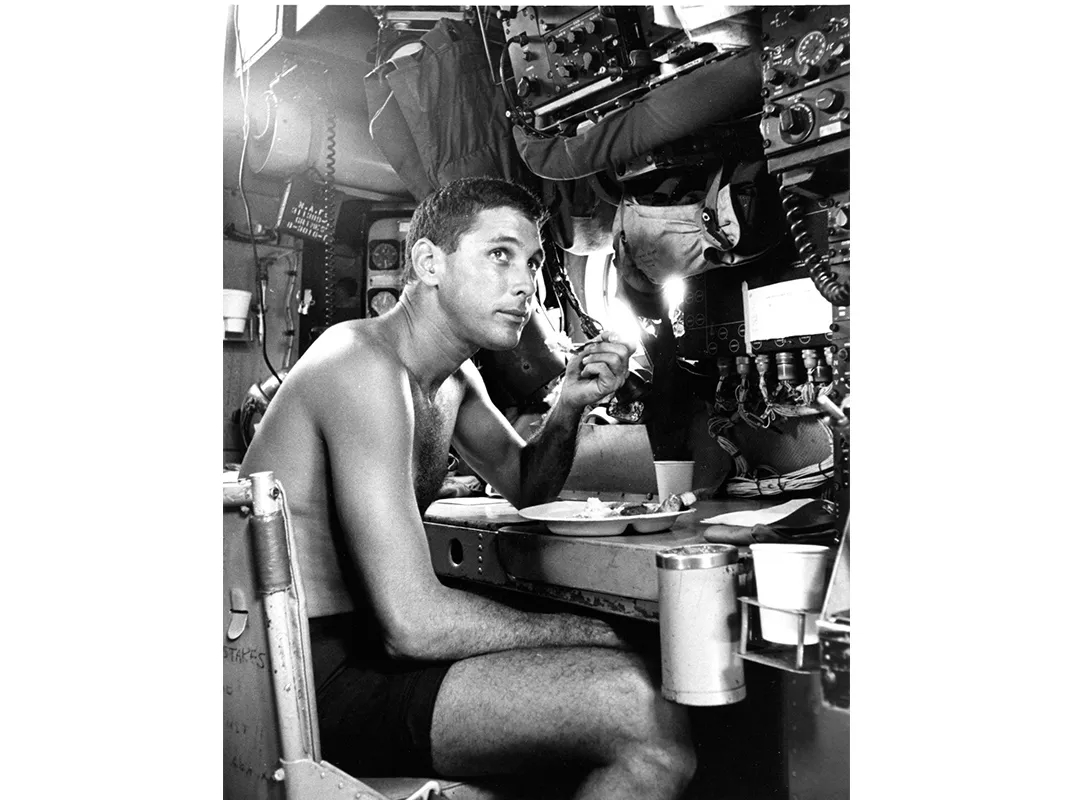

To make the crew comfortable, Martin equipped the P5M’s spartan interior with a head, a couple of bunks, and a small two-burner galley, augmented by an electric skillet.

Bruce Barth is a Marlin historian who served as an aircrewman with VP-40 (Patrol Squadron 40) from 1965 to 1967. “The mess hall ashore issued us crates of rations, including fresh steaks wrapped in brown paper,” says Barth. “I used to peel and cut the whole potatoes with a survival knife, then boil them up for mashed potatoes.” With typical missions lasting 10 to 12 hours, a crewman with good culinary skills like Barth was a prized asset. Nothing relieved the monotony of a long patrol like the aroma of grilled steaks and potatoes wafting through the cavernous hull.

To accommodate a crew of that size, the Marlin had to be large. The Marlin was so big, in fact, that a fully loaded aircraft—weighing nearly 77,000 pounds—couldn’t take off in gusty conditions without the added thrust from a pair of JATO (jet-assisted takeoff) bottles mounted on each side of the hull. With the Marlin’s twin radial engines at full power, the patrol plane commander, or PPC, would squeeze a button on the control yoke in order to trigger the JATO rockets.

Victor A. Jones, a third pilot on a VP-50 Marlin crew, told Barth about once getting the unexpected opportunity to make a JATO takeoff. “We lined up with the sea lane,” said Jones. “I missed a garbled radio transmission, depressed what I took to be the ICS [intercom] button on the yoke, and asked, ‘Are we cleared for takeoff?’ At that very moment, I heard a deep loud rumble from back aft. We were moving, and the [commander] shoved up the power on the engines. We were soon on the step, and upon reaching takeoff airspeed, lifted off, made our turnout, and jettisoned the JATO bottles. After everything was squared away, takeoff checks complete, the PPC turned to me and inquired, ‘Is there something about JATO you don’t understand?’ ”

**********

En route to their patrol areas, crews gave the Marlin’s sensor gear a rigorous checkout. Stewart Morton, a retired Navy commander, recalls that arriving on station, his crew would patrol a box above the shipping lanes, sweeping it with radar from about 2,000 feet. “Once we had a target, we’d descend to 500 feet and make two passes, one from stern to bow, and another [at right angles] across his track to make an ID.” The process of noting the ship’s masts and antennas for positive identification is termed “rigging” the vessel, and crews took pride in getting in close for a good look and snapping furiously away with a suite of cameras, some gyro-stabilized. Soon a report would be on its way to fleet intelligence with the vessel’s identity and nationality, as well as its deck cargo, course, and speed.

Mastering the Marlin was a satisfying challenge for its pilots, says Rick Davis, a VP-47 patrol plane commander in the early 1960s. “The Marlin was a stable, well-behaved aircraft,” he says. “It drove like a truck, but it was easy to fly and wouldn’t surprise you when you rolled it up in a 45-degree bank, circling 300 feet over a submerged sub.” Stew Morton adds that it “was a typical Martin airplane, very steady and predictable. Trimmed up, you could fly it with a finger.”

Davis says those traits were important because much of the Marlin’s work was done at low altitude, at night, and in bad weather. In the North Pacific, off Japan and Korea, Marlin crews were often faced with low ceilings, snow squalls, and icing. “The Marlin had anti-icing gear, but it was vulnerable in heavy icing,” says Ron Narmi, a retired rear admiral and VP-47 Marlin pilot. “Patrol missions in winter weather always caused me to fret.”

Losing an engine on the big flying boat required immediate action: Add power, control the yaw with rudder, feather the dead prop, and descend while dumping fuel and any expendable equipment. Davis recalls that during a 1960 deployment to Iwakuni, Japan, VP-47 suffered a spate of engine failures. “It turned out the Navy’s west coast overhaul facility was installing the wrong size piston rings,” he says. Fortunately, the Marlin could fly on one engine: Many a crew managed to limp hundreds of miles back to base with only one prop turning.

Once home, the flying boats excelled at settling in at the seadrome. “At night, we’d set up for a 90-knot, 300-foot-per-minute descent to the touchdown zone,” says Rick Davis. “If there were no lighted buoys marking the sea lane, you just kept stabilized in the descent and flew the plane into the water—no flare.” Taxiing to the mooring buoy was done with differential power, reversible propellers, and underwater hydroflaps—water brakes that extended from the aft hull and were controlled via the rudder pedals.

In 1967, retired Vice Admiral Norm Ray of VP-50 was at the controls for a night check ride off Coronado Island, California. Sitting in the right seat, Ray lined up for an instrument landing: He held an approach heading and eased the ship down at about 200 feet per minute. His instructor pilot, looking ahead at the lighted buoys marking the sea lane, called out the diminishing radar altitude: “You’re fine, keep it coming.” But as the Marlin splashed down, it struck an unlighted buoy. The impact tore open two of the hull’s three watertight compartments. With the sea rushing in, Ray drove the Marlin up on an empty beach. “It caused quite a stir,” he says. “We even made the evening news.”

**********

Martin introduced the improved P5M-2 in April 1954. Among its advantages were a larger fuel capacity, more powerful Wright R-3350 engines, and a distinctive T-tail, which kept the horizontal stabilizers high above the salty prop blast and ocean waves during takeoff. A forward hull facelift and repositioned nose chine helped keep sea spray from the engines. Altogether, Martin delivered 238 Marlins, the last in December 1960.

P5M-2s were equipped with the latest electronics for wartime anti-sub work. The improved AN/APS-80 radar could detect the snorkel of a Soviet sub from 10 miles out, and one sensor could detect fumes from the boat’s diesel exhaust.

Once the radar found a submarine, the Marlin crew dropped sonobuoys to home in on its submerged quarry. JEZEBEL buoys listened passively for submarine propeller and hull noises, radioing data back to the Marlin’s sensor operators. The complementary JULIE system set off small explosive charges to echo-range a sub’s position. (JULIE was named after a Philadelphia exotic dancer who had impressed off-duty Navy officials during a mid-1950s visit to the nearby Johnsville Naval Air Development Center.)

Ron Narmi, who flew the Marlin from 1957 to 1962, says his crew would tackle a sub by “dropping sonobuoys to get his course and speed, and you might even drop a ‘fence’ of them in front of him to fix his position as he passed through.” Closing in, “we’d get more localization by flying cloverleaf patterns over him, sometimes down to two or three hundred feet, at up to 45 degrees of bank with 140 knots.”

At this point, the crew employed a magnetic anomaly detector (MAD) sensor, a spike-like magnetometer projecting behind the Marlin’s tail. The MAD sensed disturbances in the local magnetic field caused by the submarine’s metal hull. “You tried to drop on a MAD contact, which was your most accurate location, because the Mark 54 depth charge had a lethal kill radius of only about 75 feet,” says Narmi. The Marlin’s best weapon was a homing torpedo, which could lock on if dropped within 500 yards of a sub. In the event of war, Marlin crews were authorized to kill any submarine their sensors identified as hostile.

While crews honed their anti-submarine warfare skills in training exercises against U.S. submarines, rarely did a crew on patrol pick up a Soviet sub. Instead, the Navy’s 10 Marlin squadrons spent most of their time on sea surveillance. They shadowed Soviet freighters during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and patrolled for communist ship traffic around the globe.

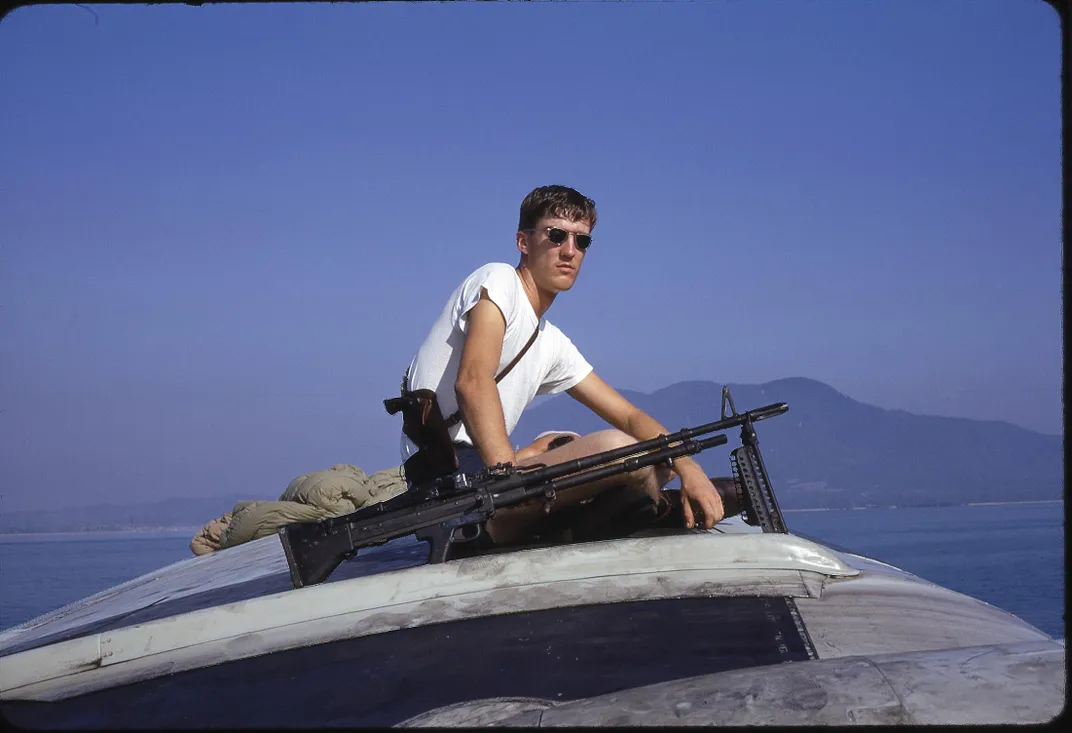

Beginning in 1964, Marlin crews picked up the pace of these missions off the coast of South Vietnam. To stop the shipborne flow of arms and ammunition to Viet Cong forces ashore, the Navy implemented Operation Market Time, an air-and-sea blockade. For three years, Marlin crews were a key element of the campaign.

From their base at Naval Station Sangley Point in the Philippines, crews flew the two-hour passage to their assigned station, ran an eight-hour patrol off Vietnam, then returned to base. To shorten transit and response times, the Navy deployed seaplane tenders to Cam Ranh Bay, which could support up to six Marlins at a time. The tenders took care of maintenance, fueling, and arming the Marlins, as well as quartering the crews.

Says Bruce Barth: “We’d pull buoy watch for our plane while moored—three or four enlisted men and one flight officer aboard for a six- to eight-hour shift. One would keep watch from the wing, looking out for enemy swimmers in the water.” Other crewmen would sack out in lashed-down sleeping bags atop their Marlin’s wing. “We caught some gorgeous sunsets up there,” says Barth. “But some nights, a Navy launch crew would cruise the anchorage, tossing concussion grenades in the water at random to deter swimmers. We didn’t get much sleep on those watches.”

Marlins pulled radar-picket duty over the fleet in the Gulf of Tonkin, and swept the sea lanes off the coast for interlopers. “We covered tracks off the coast from north of Hainan Island all the way down to Da Nang,” says Barth. “We had a bird in the air over these areas 24 hours a day, seven days a week.” Finding a suspicious target, the Marlin crew would descend to rig the ship and, if necessary, call in air or surface assets to stop an enemy vessel.

Low-altitude rigging was serious business. “We saw everything from trawlers [electronics eavesdroppers] to junks to steel-hulled freighters trying to get through,” says Barth. He remembers “taking photos of guys ripping the covers off their ship’s deck guns.” While a few Marlins were hit by hostile fire, none were ever lost to enemy action.

Though Marlins flew on well beyond their expected service life, they couldn’t compete with the Navy’s land-based patrol aircraft: Lockheed’s P2V Neptunes and P-3 Orions were faster, could range farther, and could carry more payload. Orions were also cheaper to operate. Stan Piet, author and archivist at the Glenn L. Martin Maryland Aviation Museum, says that after World War II, the Navy had plenty of bases and runways around the globe, and sea-based aircraft offered few advantages. “That’s what put the seaplanes out of business,” he says. “Land-based patrol aircraft had lower operations costs and didn’t face the corrosion and maintenance issues involved with sea basing. I’m surprised the Marlin lasted as long as it did.”

By mid-1967, Orions had supplanted the flying boat squadrons off the coast of Vietnam. Many P5M pilots moved on to Orions or other billets with few regrets, but most would agree with Stew Morton, who says: “It wasn’t a glorious airplane. It was kind of silent, doing its work over thousands and thousands of hours. It had a phenomenally good accident record. The esprit de corps of the men—the camaraderie that came from doing the job—was always good. I was proud of my time in the Marlin. It was a little sad to see it retire, but I knew it had to go.”

When VP-40 rotated back to San Diego that summer, most of the Navy’s Marlins had already been taken to the boneyard. But on November 6, 1967, the last qualified Marlin crew took its P5M-2 (re-designated an SP-5B) up for one final pass, thundering past Naval Air Station North Island in a salute to a line of Navy flying boat crews stretching back 57 years. When its sleek hull at last sliced into the waters of San Diego Bay, the era of the naval seaplane was over. That lone surviving aircraft, Bureau Number 135533, is on exhibit at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.