The Condors Quartet

Operation Lam Son 719 changed them. Then they waited for the world to catch up.

:focal(590x253:591x254)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/09/6309e3ea-88ea-4660-9994-44bfe0c991dc/condor_quartet.jpg)

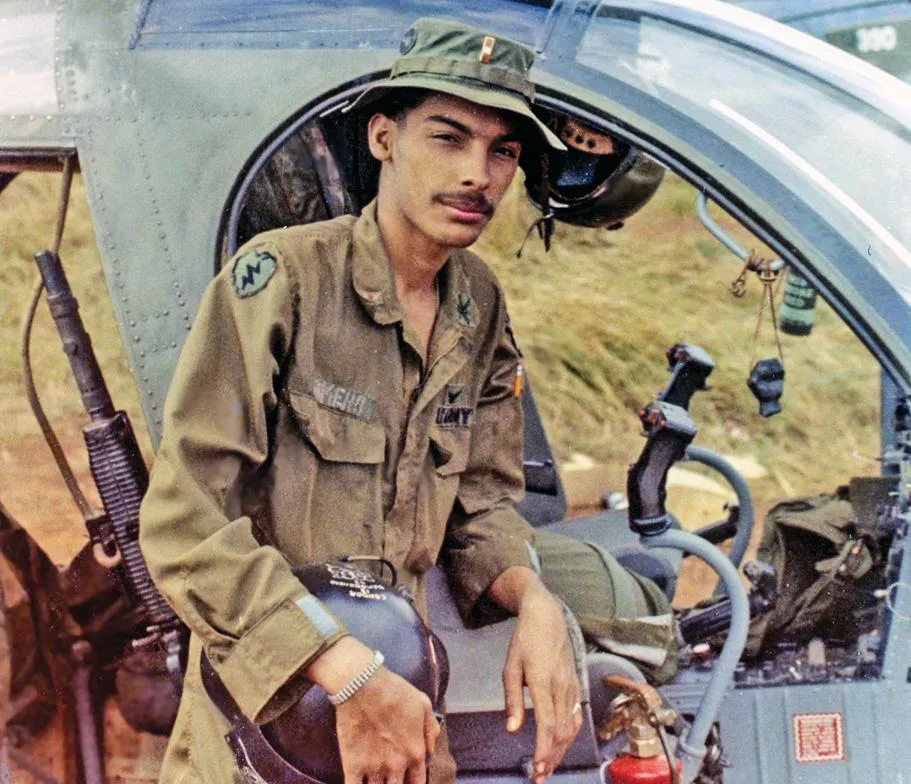

The Vietnam War entered American living rooms in television footage and newspaper photographs, but some of the most remarkable images were captured by the troops rather than professional shooters. One of those standouts is a snapshot taken at the Hue Phu Bai base in early 1971, showing four smiling men in fatigues, named Clyde Romero, James Casher, Eldridge Johnson Jr., and Bob Farris. It was no ordinary quartet. All were battle-seasoned helicopter pilots, all were in the same “Condors” unit of the 101st Airborne Division—C Troop, Second Squadron of the Seventeenth Cavalry—and all were Black.

From archived news reports and documentaries, America’s forces in Vietnam may appear to have been thoroughly integrated in a way that troops in the Korean conflict and World War II were not, but the Vietnam War’s integration happened mostly in the lowest ranks. Although eligible Blacks were drafted at a rate twice that of whites, only a small percentage gained entrance to the officer ranks. Most African-Americans sent to Vietnam, whether they volunteered for the U.S. Army or were drafted, spent their 365-day tours as combat infantrymen or in support units.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/71/29/712977e4-2cf3-4787-b7f1-f3aa035108dc/05n_dj2022_4copternampilots-111-cc-50479_live.jpg)

After their Army years, three of the men in the photo flew fixed-wing aircraft in the U.S. Air Force and National Guard, and finished their flying careers as pilots for major airlines. The fourth suffered years of post-traumatic stress from his Vietnam service—combat that won him a Silver Star for heroism during the disastrous invasion of Laos called Lam Son 719—and eventually died alone in Washington state.

Eldridge Johnson Jr. was the first of the four to touch down in Vietnam, spending his first tour as an enlisted man rather than a helicopter pilot. He was born in Arkansas in 1949, but his mother soon moved the family to Chicago. Johnson went to a state park’s open house at age 14, rode a few minutes in a light airplane, and left the field determined to be a pilot. Scraping up money for flying lessons, he soloed at age 16 but lacked the money for enough flying hours to get a license. Working as a telephone installer, and drafted at age 18, Johnson met an Army recruiter who told him about the Army’s helicopter fleet.

“I liked helicopters,” Johnson says, “and I wanted to fly those, but the recruiter said, ‘No, you can’t do that, you have to be a mechanic instead.’ ” Johnson arrived in June 1969 and spent his first year in Vietnam at a firebase in the North near Camp Evans, serving as a door gunner on UH-1 Hueys, Bell 47s, and then on the Hughes OH-6 Cayuse, which everyone called the Loach.

An expert mechanic, Johnson had the experience to qualify as a helicopter’s crew chief, and trained men who went on to that role, but months went by without his getting that promotion himself. Nevertheless he held on to his dream of moving up front. “The pilots were all white except one,” he recalls. “I said ‘OK, I’m going to do that one of these days. These guys are not the sharpest knives in the drawer.’ ”

The first step was a skills test, taken in Vietnam. On the second try, Johnson scored high enough to qualify as a warrant officer, the rank for most Army helicopter pilots. After his first tour ended, he returned to the States and received orders for the primary helicopter school at Fort Wolters, Texas.

“A lot of people quit the first day,” he says. “It was like the worst drill sergeant movie you ever saw, [the training, advising, and counseling officer] telling you you may as well quit right now. A lot of them had prior military experience and didn’t want to put up with this. Me, I wanted to fly, so I hung in there.”

Some African-American helicopter pilots felt that the Alabama towns around Fort Rucker, home of the advanced helicopter training course, posed more risks to minorities than the initial course at Wolters. But for Johnson, Wolters proved the bigger hurdle. He recalls being blacklisted along with his two white roommates for a minor infraction during inspection of their quarters. Johnson was put on a track to be washed out of the program, but then found that his roommates had been quietly taken off the blacklist. Johnson brought the evidence to the base’s inspector general’s office; the evidence he presented put him back in the program.

“From then on, everywhere I went,” Johnson says, “they knew who I was and gave me dirty looks. So there were repercussions, but nothing major.”

Johnson graduated with high marks and left for advanced training at Fort Rucker. It was understood that African-Americans off the base on leave were liable to be pulled into arguments or fights that would kill their chances to command a helicopter. “So basically I stayed on the base,” Johnson says.

After having passed all the tests, Johnson faced burnout and was close to quitting the program. “I was quite pissed off and they said ‘Go see the chaplain.’ It turns out he was the first Black Green Beret chaplain. He said, ‘If you don’t finish this, it’ll look like those fools in Texas were right.’ ”

Before leaving Rucker, Johnson heard that a sergeant from his first tour in Vietnam, one who had told him he’d never make it as a pilot, happened to be at the base. “I went to see him,” Johnson says. “I was now a warrant officer, and he’s still a sergeant. He snapped to attention and all those things I wanted to say…I didn’t. I just reached out to shake his hand, I made my point.... Nobody knows your ability, so don’t say to me ‘You can’t do it.’ ”

With his crew chief’s background, and given that Johnson had already seen plenty of combat in his first tour, the Army assigned him to maintenance-officer training at Fort Eustis, Virginia. Upon returning to Vietnam, Johnson was responsible for the upkeep of 18 helicopters including Hueys, Cobras, and Loaches. He flew when the pilot ranks were short, in addition to making maintenance test flights to verify that the work was complete.

The other three African-American pilots were making their first trips to Vietnam at this time. James Casher, the oldest at age 22, was born in Japan to an African-American father and a Japanese mother. His family moved to the United States when he was four years old. Casher graduated from a New York high school in 1966 and relocated to the Pacific Northwest. In 1970, after two years of college, he enlisted in the Army. Casher had entered the Fort Wolters helicopter school simultaneously with Johnson. Those two new arrivals were greeted in their barracks by two other Black men who had just graduated from the primary course: Clyde Romero and Bob Farris.

Romero grew up in the Fort Apache neighborhood of the Bronx and attended the Queens Aviation High School, earning his airframe & powerplant license and a high-paying summer job at Pan Am’s maintenance facility at Idlewild Airport. Romero had the grades to win a spot at the Air Force Academy, but received pushback on his application when interviewing with a lieutenant colonel. “I introduced myself,” Romero recalls, “and he said, ‘So you want to be an Air Force pilot. I said yes, and he said, ‘You’ll never make it.’ And that was that.”

The Air Force would only go as far as offering Romero a slot in an Academy prep school the following year. In the meantime, he heard about the Army Aviation program from a recent graduate of Queens Aviation. He signed up for delayed entry and arrived at Wolters in April 1969.

Romero recalls that he was treated like other Blacks at Wolters. “I was Puerto Rican,” Romero says, “but back then, if you weren’t white you were Black.” He adds that from what he experienced, “there wasn’t that much overt racism at Wolters. All were treated harshly.”

Graduating in the same 70-01 class as Romero was Bob Farris. Like Romero and Johnson, he was captivated by airplanes early. Farris went from his Philadelphia high school to junior college and graduated with an associate degree in engineering. While working as a draftsman on construction plans, he received a draft notice. After the usual battery of tests, the Army guaranteed him a place in radar repair. “I’d be stationed in the States,” Farris recalls. “Vietnam was just some other place the hell away from here.”

Despite the safe choice, Farris wanted to fly. After basic training, his test scores made him eligible for officer candidate school, West Point, and the Army helicopter school. “They showed us movies, and one was a helicopter movie,” he says. “I figured that was for me.” After several months working on radar sets at Fort Monmouth, Farris reminded the personnel office that he was still waiting for helicopter school.

“I was given three days to gather up my stuff, and then I was on an airplane to Fort Wolters,” he says. “That was my first airplane ride.”

Farris and Romero chose to take their advanced training at Hunter Army Airfield in Georgia, given warnings about the treatment of Blacks in towns around Fort Rucker.

Farris’ time in Vietnam would line up so closely with classmate Romero’s that the two had seats on the same flight to Vietnam and would finish their tour as passengers, once again, on the same airplane.

Training happened on the job. Romero and Farris began flying UH-1 Hueys on arrival at the 25th Infantry Division’s base at Cu Chi on April 17, 1970, and just two weeks later, found themselves part of President Nixon’s plan to cut North Vietnamese supply lines across the South Vietnam border. The Cambodia invasion ended 60 nonstop days of flying later.

Soon after its work in Cambodia, the 25th Infantry received orders to leave Vietnam as part of a long withdrawal of American troops. But rather than leaving with the rest of the 25th, Romero and Farris were re-assigned to the 101st Airborne Division. They would finish out their year in-country, Romero says, “while the white guys all went home.”

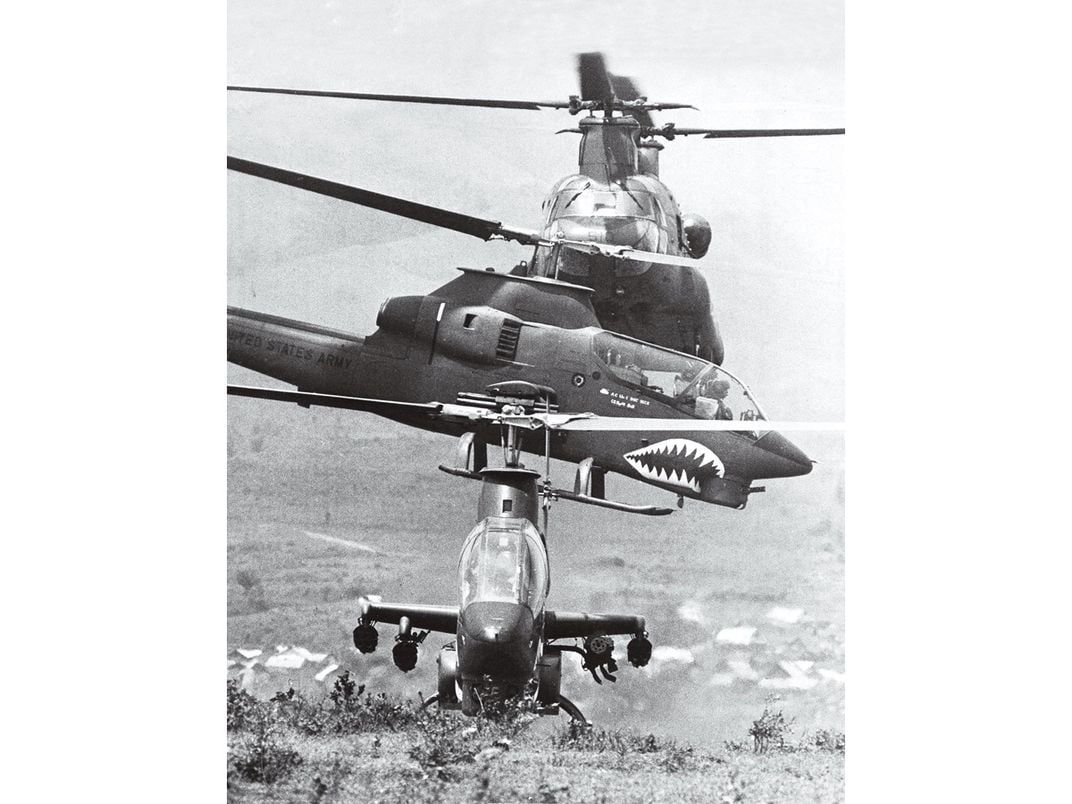

Romero and Farris were sent to different units of the 101st: Romero flying OH-6 Loach scout helicopters for C Troop, 2nd Squadron of the 17th Cavalry, and Farris flying AH-1 Cobras for the 4th Battalion of the 77th Artillery.

“I was the only minority pilot at the time,” Romero recalls of C Troop. “A lot of draftees didn’t want to be there, and there was substantial racial tension in the Army. I was surrounded by a lot of Southerners wearing Confederate symbols—but I wasn’t bothered because nobody else wanted the scout mission but me.” Romero and Farris both painted Black Power fists on their flight helmets. Johnson decorated his with the word “Flap,” a nod to the Black officer in the Beetle Bailey comic strip.

Eldridge Johnson saw the racial tension both as an enlisted man and as a warrant officer. He said it ebbed and flowed with the season. Monsoons saw the most tension, when bad weather halted most helicopter assaults. This left the troops plenty of time to catch up on news of racial and political violence back in the States.

This off-duty stress dropped during the dry-weather combat season. “When everybody’s in the heat of battle, when it’s all of you against the enemy, people don’t have time for racial differences,” Johnson says. “All that goes away and it’s almost like a family.”

Farris arrived in Romero’s unit to fill a Cobra pilot vacancy. Though Romero and Farris were close, Farris told his friend that he didn’t want to escort him on Pink Team hunter-killer missions, which combined Loach and Cobra ships.

“Clyde would fly around anything suspicious, shooting his pistol out the door,” says Farris. “Yeah, that was his style: out there. We flew together once or twice, and then I told him ‘I’m not going to see you shot down.’ ”

Loaches flew low and fast to detect enemy positions, by eye if possible, but often by receiving anti-aircraft fire. Romero’s ship would mark the spot with smoke, shoot back, then make way for the heavier firepower of the Cobra or Air Force fixed-wing bombers.

“If you took fire, you knew you’d found something,” says Romero. His Loach carried two men besides the pilot. The spotter in the left seat had an M16 and two grenade launchers. “The guy in back had an M60 on a bungee cord with a million rounds of ammo.” His ship carried extra hand grenades and what he calls an Army version of the cluster bomb: a Thermite grenade to burn through the roof of an enemy bunker, attached to a slab of “Flex X” high explosive to blow up the contents.

By early 1971, all four men were highly qualified helicopter pilots, and familiar with the peculiar dangers of I Corps’ area of operations in northwestern South Vietnam. The enemy had buried thousands of tons of supplies and ammunition in the heavily forested and mountainous terrain.

The topography limited low-level helicopter missions to daylight hours, dangerously, because that’s when the ships were most vulnerable to North Vietnamese anti-aircraft defenses. These were particularly deadly in the A Shau Valley, which bordered Laos. Though the valley lay in South Vietnam, NVA forces had occupied it since 1966. By 1970 the valley harbored thousands of NVA troops. Enemy commanders had resolved to pay any price to hold it.

The NVA’s deadliest anti-helicopter weapon throughout the Vietnam War was the .51-caliber DShK heavy machine gun. The A Shau Valley had hundreds of them, many cleverly placed at the points of a large triangle so that no single emplacement could be attacked without the American gunship taking fire from two other machine guns. Pilots believed their helicopters could usually handle hits from .30-cal. AK-47 rounds, but the bigger DShK slugs were devastating. Some of the guns protected high-value bunkers; others were placed to fire into clearings that helicopter pilots might see as suitable landing zones.

“A Shau was part and parcel of the Ho Chi Minh Trail,” says Romero. “It was active all the time. There was never a day you wouldn’t take fire.” It was understood among the pilots that if a helicopter went down, death or capture was certain if rescue took longer than 30 minutes. And many rescue attempts failed because the enemy rushed to crash sites in hopes of bringing down still more machines.

Clyde Romero’s Loach crashed onto a slope in A Shau that the pilots dubbed Tiger Mountain for its bomb-scarred face. Given reports of extra enemy activity in the valley that day, Romero says, “We’d decided to come in by Hamburger Hill, west from the Laotian side, instead of from the east, from South Vietnam. But as soon as I let down, I started taking .51-caliber fire—they got me—and I autorotated into elephant grass at the base of the mountain. We knew we’d crashed in the middle of an NVA fortification, because right away I could hear Cobras shooting rockets around me.” The Cobras held enemy troops back long enough for a Huey to pick them up.

One casualty that hit Romero particularly hard was the death of Captain Wilbur Latimer. On January 19, 1971, as Romero prepared to fly a routine mission, Latimer approached, and said he wanted to fly that day. During the flight, the helicopter took ground fire, killing Latimer. “He took my mission and was killed,” says Romero. “I live with that every day.”

Until January 1971, other dangerous strongholds along the Ho Chi Minh Trail network in Laos had been off-limits to U.S. forces—except for small clandestine missions, such as inserting squads of special forces and indigenous fighters. This changed when South Vietnamese ground forces, backed by American air power, launched a major invasion into Laos. Code-named Lam Son 719, it was expected to be as successful as the invasion into Cambodia seven months earlier, which had met most of its objectives at little cost. By targeting enemy camps and supply dumps along Highway 7 as far as the town of Tchepone, Lam Son 719 was supposed to foil future NVA plans for a second, Tet-like wave of attacks in South Vietnam. It would win time for the United States to transfer more responsibilities to the South Vietnamese army, called ARVN. But Lam Son 719 suffered from security leaks and poor preparation, achieving only brief, symbolic gains at terrific cost, as the following weeks would show.

In January Casher, Romero, and Farris found themselves together again at Khe Sanh, a war-torn firebase that had been abandoned to the North Vietnamese, then recaptured long enough to support the Lam Son invasion.

Jim Casher’s longest day started when he and Captain Jim Kane were dispatched to provide cover for a Cobra that had crashed in Laos. Their own Cobra took so many hits from heavy-caliber guns they returned to Khe Sanh to pick up another. They headed back to the fight, and as Kane recalled later, Casher was remarkable for his calmness under pressure. There was reason to worry: As the Cobra moved in to lend support, a DShK gun found their range and sent an incendiary round into the crew compartment. On fire and with damaged controls, the Cobra crashed in a ravine. Casher and Kane climbed out and were rescued by a Huey.

Seasoned pilots who knew the special dangers of I Corps territory were alarmed at some of the Army Aviation reinforcements arriving from the south: flatland pilots in aging “C” model Huey gunships and OH-58 light helicopter scout ships.

“In Lam Son, we had pilots coming up from the south who didn’t know the score,” says Eldridge Johnson. “It’s why you had 10 Hueys shot down in one assault.”

“We knew the area,” says Romero, “and you needed at least a month to train for that.... It’s like a cop going into an alley. You can have all the bullets and radios in the world, but if you don’t have a feel going in, the street smarts, you’re going to be dead.”

The cost of Lam Son was perhaps as many as 8,000 ARVN troops killed in action and 650 helicopters damaged or destroyed. The 101st Airborne alone lost 84 of its aircraft. If Lam Son had any disruptive effect on the NVA, it was hard to tell, because the enemy launched a major offensive a year later featuring 600 medium and light tanks.

“Was that avoidable?” says Romero. “Oh, my God, yes. Our commanders didn’t want to pay attention to the intelligence reports…. [The enemy] had at least five years of experience with our helicopters, and we got our ass handed to us in Lam Son.”

All four men completed their Vietnam tours in 1971.

It was clear to Johnson, Romero, and Farris that if they wanted to make flying a lifetime career, it wouldn’t be in the Army, because the transfer of equipment to the South Vietnamese was leaving Army Aviation with a huge surplus of helicopter pilots. Knowing they’d need experience in fixed-wing aircraft to have a hope of joining the airlines, after finishing with the Army all three transferred into the Air Force and won commissions there. For Blacks to nurture a hope of flying for the airlines took considerable optimism and patience.

Six years after Vietnam, the doors finally opened. Bob Farris joined Allegheny Airlines in January 1978; Romero and Johnson began their airline careers three months later.

“Deregulation had hit, and that led to a lot more minorities hired as pilots and flight attendants,” says Romero, who started with Piedmont. “Airlines had traditionally been all white, but not after 1978 and 1979. Airlines needed people of color, who could speak other languages. That really changed the whole social makeup.”

Casher didn’t go that direction. He stayed in the Army until 1975, followed by Army Reserves through 1983. Then he went into seclusion, knowing a few neighbors in his remote corner of southeast Washington but not telling them about his medals for heroism. Shortly before Casher’s death from illness in 2011, Eldridge Johnson found him living hand-to-mouth in a modular shack. “We talked in the rain for maybe 15 or 20 minutes,” Johnson says. “I looked forward to seeing him again, but unfortunately it didn’t happen.”

Nearing retirement as an international pilot for United, Johnson flew his 747 along a Far Eastern route that had him overnighting at Ho Chi Minh City, the former Saigon. Johnson walked the streets and remembered the year he spent in country. It was surreal, he said, smelling the familiar odors and seeing the same moped-jammed streets, but also passing a Mercedes factory. Romero’s routes as a senior pilot for American didn’t bring him back to postwar Vietnam, but he did take up one last thread from his scout pilot days in I Corps. “After I saw that movie We Were Soldiers,” Romero says, “it hit me that [Wilbur Latimer’s] people needed to know how he got killed, so I picked up the phone. I knew he was from Searcy, Arkansas. There was a lot of racial tension, but Latimer was not that way. He was for equal rights. We had become very close. I called his sister, Dorothy, and I said, ‘I’ve got maps and pictures of your brother alive. I can come to Searcy and I can close the loop.’ So I flew to Little Rock, and met with his mom and dad, his sister, and wife. They really wanted to know, so I told them exactly what happened. Here I’m a person of color and they were white as snow, and we’ve been in touch ever since.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/1a/661ae741-675f-4a41-9def-ce876cf2f5ec/05h_dj2022_4copternampilots-farrisvn_live.jpg)