Confessions of a Flight Engineer

Flashlights, timers, and breath mints required.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Above_and_Beyond_11-01-11_3_FLASH.jpg)

At last, I looked like the airline pilot I had long planned to be, striding purposefully through the terminal on my way to your next destination: close-cropped hair, navy blue uniform, billowing ankle-length overcoat. It was 1996, and I had just become a Trans World Airlines flight engineer on the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar, based in New York City.

No female airline pilot wants to look too butch, or worse, too feminine. The hardest part was finding shoes. When you’re preflighting an aircraft, you can’t run around a snow-covered ramp in high heels. I had met one female pilot sporting steel-toe boots. I found medium-heel loafers in which I could sprint down the gateway to catch a commuter flight home to the West Coast. The best part about being a flight engineer? I could wear my sunglasses inside. Otherwise, no dangly earrings, wear your hat, and as a courtesy, no perfume. The next quandary was that of a tie. Women’s crossover or men’s clip-on? During a fight with an inebriated passenger, some captain had gotten his head yanked down by his tie. So men’s ties were now clip-on. I went with the women’s crossover, and for jewelry, a TWA logo pin on one side and a Lockheed L-1011 tie tack on the other. We had cell phones hooked to our belts, photo ID cards clipped to our shirts, and money in our pockets, because no self-respecting female pilot would be caught dead carrying a handbag while in uniform.

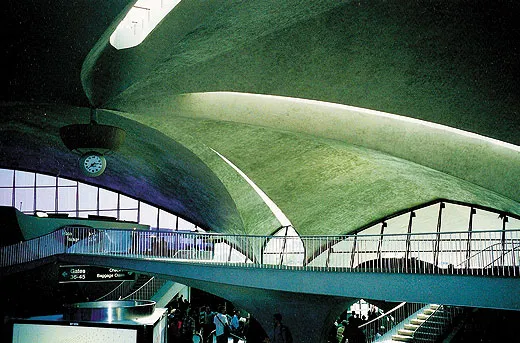

For many of us airport nerds, walking through the TWA terminal at Kennedy International Airport in uniform was the pinnacle experience. The building was all glimmering white, organic shapes, like what the inside of a toothpaste tube might look like. Posters of destinations like Egypt, Spain, and India (and of course Disneyland) lined the walls at passenger check-in counters. Long oval tubes drew you from check-in to departure gates.

Adapting to being on call was in no way glamorous, especially when you had to commute to your working base (you had to be practically ancient, seniority-wise, to be based at Los Angeles; none of us junior pilots would be based there for years to come). When paged by crew scheduling, we had 15 minutes in which to call back and two hours to show up at the airport. Schedulers ruled our world; we brought them candy at Christmas. But no matter what, we got calls to be at the airport ready for aircraft pushback in 30 minutes, or worse, calls informing us that our trip had just been extended for another day or two—cancellations due to weather, mechanical, aircraft swap, or crew rest requirements. And we said Thank you and learned to carry extra undies and uniform shirts.

Before and after working trips, commuting airline employees used a crash pad for sleep. My first crash pad was a long-term rental hotel room in Hempstead, Long Island, with 11 flight attendants, one gay male and 10 women, although the most people I ever stayed with overnight was four. There were two double beds (yes, during the night someone could climb in with you) and two single roll-aways. Maid service changed the sheets and towels, a refrigerator and microwave enabled light snacking, and one bathroom with a sink and shower had to suffice. At night you coordinated with the others about departure times and planned showers accordingly. It was all very civil and a lot cheaper than paying for hotel rooms on an as-needed basis. Another hardcore sleeping option I found ingenious: Pilots had RVs in the employee parking lot.

Being on call did not mean you could spend the day touring the city. Usually it was only during a long New York layover that you went to the theater, ice-skated in Rockefeller Center, skipped through Central Park, or shopped for fake Rolexes on Canal Street. We filled our days with exercise, magazines, or walks past seedy neighborhoods to the Roosevelt Field mall, built on the site from which Charles Lindbergh departed on his 1927 solo transatlantic flight. Often my training partner and I, the two token female pilots in our new-hire class, would pick up face masks, nail polish, emery boards, hair conditioners, and lotions for what we dubbed Day of Beauty. I’m not sure it did much for our appearance, but it passed the time.

Once called in, you reported to the operations building, where you picked up paperwork and usually met the rest of your crew as they signed in. You also had to retrieve your flight bag, which required you to remember precisely where you had put it: there were about 500 others that looked exactly like it. Mine had my name on it along with a little gold engraved TWA logo because I planned to stay with TWA forever. Your flight bag was equivalent to a businessman’s briefcase, with Jeppesen approach charts tailor-made to TWA’s landing specs for the nation’s airports, systems books, and the airline operating handbooks that all three cockpit crew members carried.

Flight engineers were also required to carry flashlights, pens, screwdrivers, navigation logs, and timers for fuel management. A final item—mandatory in my eyes: breath mints. It all amounted to an extra 25 pounds hanging off your “rolly” bag, which held your clothes and toiletries.

The flight engineer’s normal-procedures checklist was only two pages. Some parts you did silently, some you said out loud. I had my own seat, a desk with drawer, and a panel with triple redundancy for each of the L-1011’s engines. I started by testing systems: electrical, pressurization, fire detection, air conditioning, warning lights, and fuel, and confirming quantities of fuel, oil, oxygen, and hydraulic fluids. Usually I was the first one on the flight deck, responsible for setting it up before the pilots arrived, as well as getting power to the airplane via the auxiliary power unit so the flight attendants could begin their own before-start checklists. Most important, the temperature in the cabin had to be regulated and coffee brewed.

During the taxi for takeoff, I called the dispatcher with the final calculated weights of the aircraft, including fuel, passengers, and cargo, and received the takeoff data and performance information the pilots were waiting for. During cruise, I managed the fuel and crossfeeds and searched for leftover girly pictures, which soon, under orders, disappeared altogether, which was a shame. It was like an Easter egg hunt: The better you knew the flight deck, the better your chances of finding a pin-up inside a visor or on the back of a knob cover.

During descent, I monitored cabin pressurization. The temperatures in four zones—cockpit, first class, mid, and aft—were controlled largely by airflow, which pressurization changes during ascent, cruise, and particularly descent kept in constant flux. To minimize passenger discomfort, I had to plan ahead when selecting the rate of pressure change—too high a rate would result in pain in Eustachian tubes and screaming babies; too low a rate and you couldn’t open the doors after landing. On approach and landing, I called for the data to calculate speed settings and get a gate assignment.

We were told that during the one-year probation, you didn’t want anyone to learn your name. That meant: Don’t haggle with the schedulers or crews, wear your hat, don’t drink in the airport bar while in uniform, and don’t bust Federal Aviation Regulations by flying low over Grandma’s house. No one wanted to do the rug dance in the chief pilot’s office: shuffling your feet from side to side while getting hollered at, displaying a contrite expression, and swearing you’d learned your lesson and would never do that again.

After 10 months, we were able to brag that we had served as flight engineers on the L-1011, which TWA retired in 1997. I upgraded to first officer on the McDonnell Douglas MD-80. It all happened in my first year at TWA—a glorious introduction to an aviation career.