Crash Course

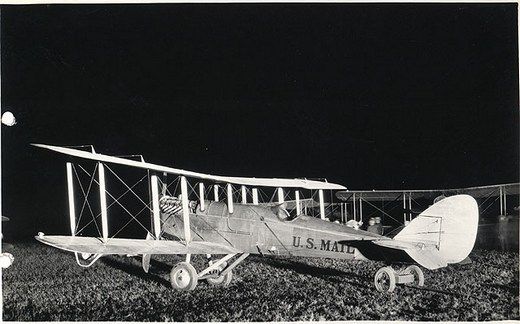

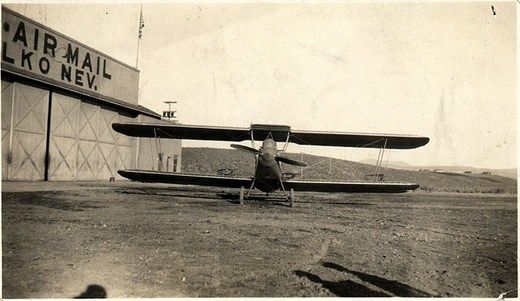

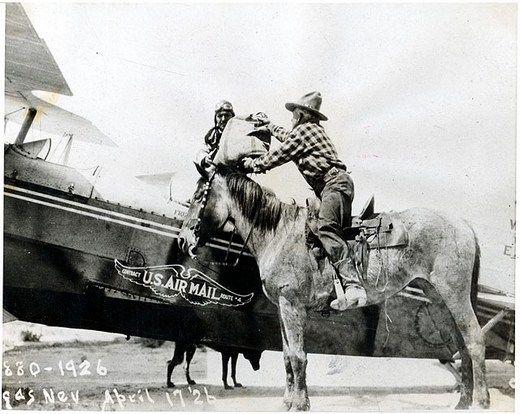

Accidents were everyday occurrences in the early days of airmail. Part of the problem was finding the right airplane.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/7d/237d8cc6-f0a6-4656-a419-6f317f6a6638/gardner_goggles.jpg)

On May 2, 1918, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Damm and Major Oscar Brindley of the U.S. Army Signal Corps (soon to become the Army Air Service) were killed testing a U.S.-built de Havilland DH-4 biplane at South Field in Dayton, Ohio. Major Reuben Fleet, newly assigned to take charge of the airmail, and Lieutenant Colonel Thurman Bane were part of a group of airmen dispatched to determine the cause of the accident, and to evaluate the DH-4 for use in the Aerial Mail Service. The War Department had announced that it would inaugurate airmail service, in part so that military pilots could gain valuable cross-country flying experience. With service scheduled to begin May 15, the proposed route would link Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and New York.

At Wilbur Wright Field in Dayton, Fleet was asked to test fly another DH-4. Bane recounted in his diary, “[Fleet] took off, flew the ship beyond the field’s length, took it to 6,000 feet, banked it with gentle and then steeper banks, looped it four successive loops with the power on, then stalled it deliberately and kicked it into a spin which he came out of 800 feet from the ground. Upon landing we gave him hell for spinning down so low, until he peeled off his shirt and wrung out the perspiration, remarking that he’d pass up lunch.”

The report Fleet submitted noted that “the Air Service [has] no airplanes capable of flying non-stop from Washington to Philadelphia or from Philadelphia to New York,” and requested that the inauguration of airmail service be postponed in order “to obtain Curtiss JN6H airplanes with double fuel capacity.” Fleet later wrote that Postmaster General Albert Burleson “went into a rage over the suggestion for deferment, stating that he had already announced to the Press that an Army Aerial Mail Service would start on 15 May.” Three days before the scheduled inauguration, six Curtiss JN-4Hs were delivered—in crates. In just 72 hours the airplanes had to be assembled, serviced, tuned, and flight-checked. Crews managed to put together two of the airplanes and borrowed a third by the deadline.

But after just one week of service, two of the original six airplanes had been destroyed, having flipped over upon landing. Fortunately, the Curtiss R-4LMs began to arrive. But although the R-4 was faster and had a longer range, it also was prone to flipping over. Plagued with inexperienced pilots, flimsy airplanes, and spiraling expenses, the War Department decided after just three months that fighting one war was enough, and relinquished operations to the Post Office, effective August 12.

The Post Office, which had always expected to run the airmail service, was ecstatic, and told prospective pilots that they would use Standard JR-1 airplanes. In spite of the War Department’s myriad troubles delivering the mail, second assistant postmaster general Otto Praeger decided to expand the route to Chicago immediately. But there was a hitch: While the JR-1B worked well on the New York-Washington, D.C. line, it couldn’t carry the 300-pound loads required for the Chicago leg.

In late 1918, Secretary of War Newton Baker met with Praeger to discuss the transfer of aircraft to the postal service. Since the November 11 Armistice signing, Praeger planned on surplus de Havilland 9s, as well as twin-engine Handley-Page aircraft. Twelve Handley-Page aircraft were to be sent at the rate of one every 10 days. But postal authorities got only one—and that, on the eve of the inauguration of the New York-Chicago route. The War Department stopped delivery and took back the airplane already handed over.

In a confidential letter from Praeger to Baker, dated December 13, 1918, and now in the National Air and Space Museum’s archives, Praeger wrote:

My dear Mr. Secretary,

I am advised that the Handley-Page machine which was completed and delivered to us and receipted for has now been either taken back by the military authorities or will be demanded on the ground, I understand that it is needed by the Army. It is incomprehensible to me how the two Departments can ever cooperate if military officers can pursue a policy of give and take back, release and rescind, from day to day.... Reverting again to the decision to let the Post Office Department have 100 de Havillands, I trust that you will be able to see your way clear to have these planes delivered to us either assembled or unassembled.

The New York-Cleveland-Chicago route was opened on December 18, 1918—and service was suspended just five days later. The DH-4s were partly to blame. With lethal stall characteristics, a high landing speed requirement, and landing gear too frail for the weight of the aircraft on rough fields, the modified de Havillands were almost as big a challenge to the early mail pilots as the weather. Pilot James Edgerton later labeled them “a deadly liability.” In a memo (also in the Museum’s collection) written to the postmaster general, Praeger outlined his frustrations:

Upon the assurances of the War Department officials that, with the close of hostilities, the Post Office Department would be enabled to obtain and utilize in the Aerial Mail Service a large quantity of DeHaviland [sic] and other planes, the Post Office Department announced the opening of the New York-Chicago airpost route December the 15th. The DeHaviland planes which the Department expected to obtain were the type known as DeHaviland No. 9, which is said to be a safe and substantial aeronautical work.... The Secretary of War advised that he could not give us the DeHaviland 9’s...but that it would be easy to furnish the Post Office Department with what DeHaviland 4’s would be needed.

The DeHaviland 4 is a weak piece of construction, the fusilage [sic] breaking and the landing gear crumpling in a great percentage of the instances where landings were affected.... In a majority of cases, where landings have been attempted, they have resulted in crumpled landing gears and complete demolition of the planes. It would seem that these planes were designed for front-line work in battle and not built to withstand normal daily landings, on the theory that a plane that makes a forced landing within the enemy’s lines is a lost ship and might as well crack.

Praeger then detailed the dismal record of the DH-4, noting 10 accidents in just 12 days: everything from crumpled, splintered, and faulty landing gear to “ship broken completely in halves and demolished.” A thorough inspection of the aircraft “revealed not only poor material but faulty design.” Anticipating charges of pilot error, Praeger pointed out that five of the 12 aviators “were ‘aces’ in the war in France.... The other aviators were either old experienced exhibition and army flyers or instructors at the Army flying fields.”

Eventually, the Lowe-Willard-Fowler Company of College Point, New York, would come up with several ways to strengthen the DH-4. The fuselage was rebuilt with steel strips; the landing gear fitted with a heavier axle and larger wheels; the pilot’s cockpit moved to the rear compartment; in all, there were close to 20 major changes that finally made the DH-4 a capable mail carrier. The de Havilland 4 would become the workhorse of the Postal Service, with more than 200 serving the organization over a period of eight years.