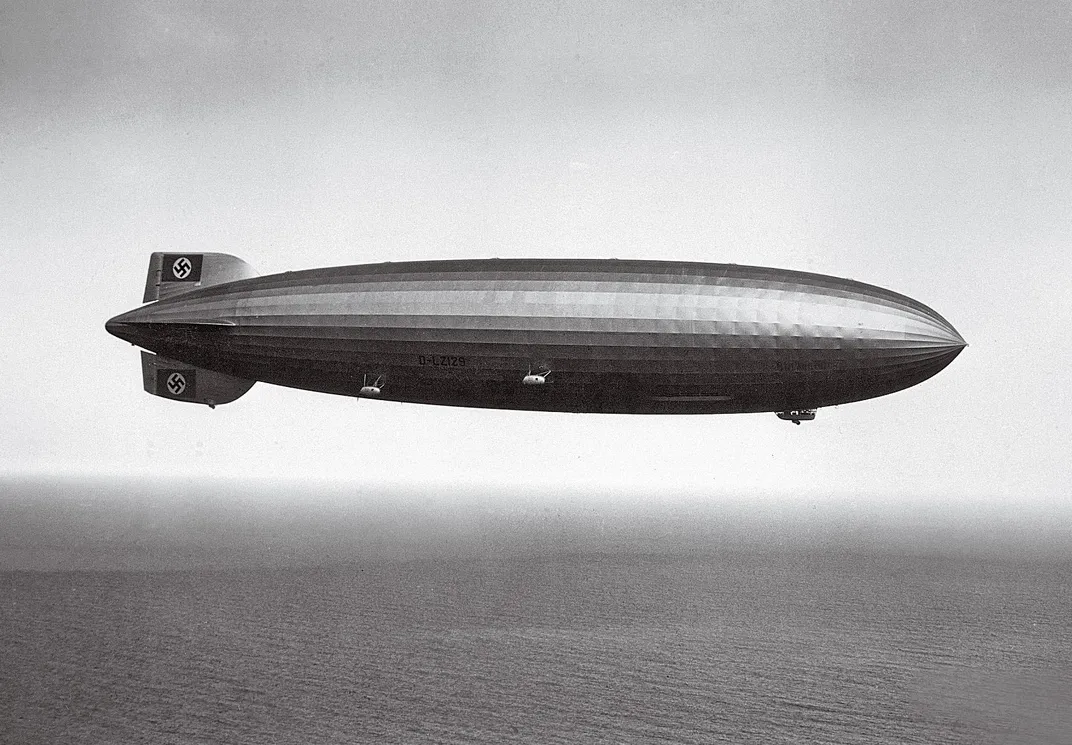

Across the Atlantic on the Hindenburg

“Europe to America in under 60 hours—incredible!”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/10/35/10356c07-8251-48b4-ae19-13c5e867ef55/05-1a_as2021-passengers_hindenburgwindows-2011-64_live.jpg)

It was a matter of Cambridge regulations. In the summer of 1936, my brother was getting married in Canada and I was to be best man. We were both booked on the Queen Mary, but at the last moment I found that I couldn’t go by ship. I had passed my exams, but to get a degree one had to spend 56 consecutive nights on campus. If I took the Queen Mary I would be one night short, and the next ship wouldn’t reach Toronto in time for the wedding. It looked hopeless.

Then my father saw a notice about the German airship Hindenburg. Passenger aircraft of the time could not cross the Atlantic in one hop, but airships could. Hindenburg was to make its third North Atlantic crossing at precisely the right moment to solve my predicament. The fare was £80, twice as much as second-class passage on the ship Normandie, on which I later returned.

I didn’t realize how big Hindenburg was until I saw its nose sticking out of the hangar in Frankfurt am Main, which my father and I had reached by airplane to Paris and train. It was just over 800 feet long, four-fifths the size of Queen Mary. At takeoff, it weighed 240 tons, 20 of it passengers and freight.

Hindenburg carried just over 50 passengers—and a crew of 45! After the ground crew walked the ship from the hangar, we boarded by a stairway in the belly. Then Captain Ernst Lehmann leaned out the window of the gondola and signaled the ground crew foreman, who blew his whistle. Half a ton of water splashed down from the ballast tanks before the 16 hydrogen bags in the hull began to lift us up.

There was absolute silence. Slowly we rose, and the faces of those seeing us off grew smaller. At about 200 feet some hydrogen was released to reduce the lift. Four diesel engines roared to life, and we swung toward the sunset and the Rhine.

Inside the hull were two decks with windows. The upper deck had two 50-foot promenades with a dining salon and a lounge, complete with grand piano. Twenty-five heated cabins with double berths had hot and cold running water. I leaned on a window sill and stared down in fascination at the Rhineland countryside below. Shining down from the nose was a powerful searchlight. I saw woodlands and a bend of the great river where we crossed it. Airship pioneer Hugo Eckener was a passenger on this flight. “You have seen the cathedral of Cologne?” he asked me. I said I had not. “Then I think we take a look at it,” he said. Two hours after we had lifted off we came to the suburbs of the great city. The two spires of the cathedral rushed into the circle of light.

I stayed at the window all night, watching. I saw Rotterdam, with big ships lying alongside the wharves in a haze of smoke, then here and there the flash of a small Dutch vessel in the North Sea. Eventually we reached the English coast over the flames of Middlesbrough’s blast furnaces. It was dawn when the sands of the Solway Firth shone up to us. We cut across the southwest tip of Scotland and over the Atlantic. When the sun rose astern there was no land in sight.

It was not until the third day that we reached Newfoundland. The island was shrouded in cloud, with only a rare parting that revealed the forests. But even above the clouds I could tell how high we were by glancing at my watch. Instead of an altimeter the airship had an echo sounder, which directed a compressed-air whistle earthward. After striking the sea or the ground, the sound bounced back to the hull. The interval between the signal and the return automatically recorded the altitude in the control cabin. Knowing that sound travels roughly 1,100 feet per second, I was able to make the calculation myself. We were at about 1,100 feet.

An airplane uses fuel on its journey and so becomes lighter. Less power is needed to keep it aloft, and the landing is easier when a ship is not fully loaded. But an airship has to maintain weight to prevent it from rising too high. Any weight lost through fuel consumption must be compensated for. You can valve off hydrogen to reduce lift, but this is risky, and the airship would have to refill with hydrogen before the return trip.

To maintain altitude, Hindenburg would brush against clouds and collect rainwater in gutters that fed the ballast tanks. If we passed through a shower every few hours there was no need to release gas. There were occasions when no rain was available, but we were rarely far from a suitable shower.

On our third night, we neared the New England coast. I had told Eckener that my brother was aboard Queen Mary, heading for New York. “I think we visit the bridegroom,” he said, smiling. About two hours out of New York, we caught up with the ship in the dark, and as our searchlight beam ran up on it, the ship’s crew turned on the floodlights.

Just after dawn we came in right over the Statue of Liberty. I gazed across New York harbor at the mass of skyscrapers on Manhattan. Then we turned, slowly losing altitude until we saw the Lakehurst airfield in New Jersey with its mobile mast, to which our nose would be moored. The ship came up into the wind, and the engines slowed until we were hovering at about 200 feet. When we were quite still, some hydrogen was valved off, and the great airship began to descend, slowly at first, then faster. Some 250 men raced across the grass to grab the landing lines. Only when we were perhaps 30 feet from the ground was the fall slowed by the release of a shower of water. We landed on our single wheel with a gentle bump.

Europe to America in under 60 hours—incredible! We had averaged 68 miles per hour on the trip. But Hindenburg would make only another eight crossings. On May 6, 1937, it fell in flames over Lakehurst after waiting for storms to clear the area.

I felt I had lost a friend. And I knew that airships were finished. The next generation would never see that enormous shape in the sky, hear the odd squeak of the echo sounder, see the shaft of light shining down from the nose.

Twenty years later I was flying the Atlantic in a Constellation. The flight attendant pointed out the window at the southern tip of Newfoundland. “That’s Cape Race,” she said. Watching the lighthouse fade away, I recalled how Eckener had stood behind me as I peered through broken clouds. “Kap Rasse, mein Herr. In 16 hours we shall be landing. Perhaps sooner.”

Roger Pilkington, who died in 2003, was the author of more than 20 books. He wrote about his airship voyage in 1992.