Crossing the Atlantic in a Mustang, With Mr. Conservative in the Pilot’s Seat

Even when you’re the world’s best, it pays to be prepared.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c5/2f/c52fda14-b543-419f-ab52-c4999697b646/berlin_express_day_006_mag_001_-3.jpg)

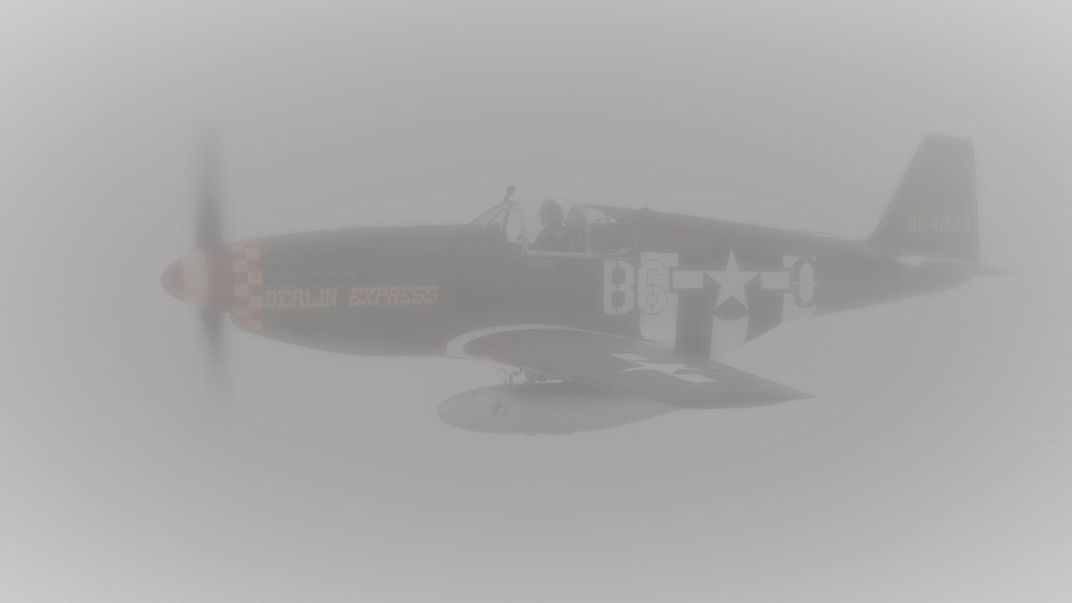

If you’re Dan Friedkin and you’ve just bought one of the most exquisitely restored P-51 Mustangs flying today, and your plan (as the founder of the Air Force Heritage Flight Foundation) is to take it to an airshow in England, who would you choose to ferry your priceless warbird across the nasty North Atlantic? You would choose the world’s highest-time Mustang pilot, who has more than 9,500 hours in the type. And that is how Stallion 51 Corporation’s Lee Lauderback came to be celebrating Independence Day with the British (Happy 4th from your former colony!) at RAF Duxford after a 5,470-mile journey from Friedkin’s ranch just south of San Antonio, Texas. The Mustang, Berlin Express, had been invited to fly with the U.S. Air Combat Command’s F-22 aerial demonstration team at the Royal International Air Tattoo at RAF Fairford, England this weekend (although that plan, for reasons to be explained, eventually fell through).

Two years ago, Berlin Express scooped up every restoration award going, and touched hearts for being painted as the P-51 flown by Bill Overstreet, the World War II pilot so famously determined to shoot down a Messerschmitt Bf 109 that he followed the German right under the Eiffel Tower. And got him. (If you want to see why John Muszala’s Pacific Fighters restoration shop won all those awards, look at Scott Slocum’s photographs.)

“When Dan got the Mustang, he thought how neat it would be to recreate the North Atlantic crossing,” says Lauderback, referring to the hopscotch route flown during Operation Bolero in 1942 to deliver badly needed bombers and fighters to the British. After a few U.S. stops, Lauderback flew the identical route: Bangor, Maine; Goose Bay, Labrador; Narsarsuaq, Greenland; Keflavik, Iceland; and Wick, Scotland. Those are long stretches of ocean to cross in an airplane with a single engine designed more than 80 years ago.

“I just put that out of my mind and focused on the mission,” Lauderback says. “But every time I saw an iceberg, I felt a little bit better. I thought Oh, I could just ditch close to the iceberg and climb up on it, and people were like ‘Yeah, right.’ ”

The time to think about those long stretches of water was beforehand, and Lauderback went prepared. “I asked for a multi-engine escort airplane that could do all the admin, paperwork, and navigation, and could carry mechanics and spares,” says Lauderback. Friedken’s response: Check. A Beechcraft King Air 350i, capable of flying the same speed as a Mustang equipped with drop tanks, flew escort. Lauderback also asked for military water survival gear, and again: Check. Under his flight suit, the pilot wore an exposure suit with rubber seals. He also wore flotation gear, and a standard military harness to which a life raft is attached, plus a vest with pockets for military beacons and com equipment. “If I ditched the airplane and got into the raft, I could communicate with the King Air. Serious professional equipment,” he says.

With those precautions in place, Lauderback could relax and enjoy the scenery, which was magnificent. Looking out over Greenland and glacier, Iceland and ocean, he says, “You realize you’re pretty insignificant in the big scheme of things.”

Lauderback’s Mustang buddies sometimes give him a hard time for his penchant for preparedness. When Louis Horschel, whom Lauderback trained to fly Mustangs and who flew right seat in the King Air on the trip, heard about his decision to make the crossing, he said, “Mr. Conservative finally comes out of his man cave and does something exciting.” But Mr. Conservative’s cautiousness has saved the bacon of more than one wannabe Mustang pilot. The airplane, famous for its powerful torque and abrupt departure from control during high-G maneuvers, demands training. When I first interviewed Lauderback 20 years ago, losses of pilots and Mustangs had been high: In 16 years, 16 pilots had been killed in accidents and 16 P-51s lost. Lauderback founded the company Stallion 51 in part to stem that tide.

In keeping with his “Be prepared” philosophy, Lauderback took the time before his Atlantic crossing to shoot an instrument approach in tight formation with the King Air, a precaution that served him well on the last leg of the trip, from Wick to Duxford. The weather, which had held for the transatlantic hops, was so bad that at times, even in tight formation, Lauderback had a hard time seeing the King Air, which was just feet away. When he thought it couldn’t get much worse, they hit turbulence. He was comfortable in the adverse conditions, mainly, he says, because Horschel was along: “We’ve flown formation and we know each other and are familiar with all the calls.”

Although crossing the Atlantic in a piston-powered aircraft is rare, it’s not unheard of. Ten years ago the P-38 Glacier Girl was going to do it, but was foiled by engine trouble. That didn’t stop airshow pilot Ed Shipley from making the crossing that same year in the TF-51D Miss Velma. (Gotta love those Merlin engines! Shipley and Friedkin fly left and right wing in the world’s only P-51 aerobatic team, The Horsemen, with warbird master Steve Hinton flying lead.)

Among the team of people Lauderback credits with making this summer’s flight a success was a highly experienced “crossing guy”: Kevin St. Germain, who has ferried aircraft on more than 500 transatlantic and transpacific trips. Also a part of the team: Richard Lauderback, Lee’s brother and the maintenance wizard at Stallion 51, and the younger John Muszala—known in warbird circles as Young John, to distinguish him from his dad—who played a big part in the restoration and knows Berlin Express inside and out.

Lauderback also had a bit of luck on his ocean crossing. Besides good weather over the water, the P-51 operated perfectly and the Merlin purred. It performed on its practice runs in England when Friedkin and pilot Rick Grey flew it. But when Grey flew a first pass at the Flying Legends Airshow in Duxford on July 8, the Mustang shed its canopy. Grey landed unharmed, but had the canopy come off a few days earlier, it could have been a more serious mishap. “A convertible over the North Atlantic would have been a little chilly,” Lauderback said.

Besides luck, Lauderback took something else along on his trip. Overstreet, who knew of the Pacific Fighters’ P-51 restoration but died before the work was complete, donated his pipe to the project; when the Mustang was sold, the pipe conveyed, and it crossed the ocean too—in the King Air. Lauderback says he thought, “If I lose that, those guys would say, ‘Yeah he didn’t make it, and worse, he lost the pipe.’ ”

Unfortunately, without a canopy, Berlin Express won’t be flying with an F-22 in Fairford this weekend after all. Another P-51 will take its place. But thanks to Dan Friedkin, the Mustang had its homecoming. Though it’s painted as Overstreet’s P-51, the airplane actually served in England with the U.S. Ninth Air Force 363rd Fighter Group, stationed at RAF Staplehurst. During a training exercise on June 10, 1944, its pilot bailed out and the Mustang crashed. Almost 75 years later, as one of the best known Mustangs flying today, it made it back to British soil.