Crowdsourcing History

Smithsonian volunteers transcribe everything from Apollo stowage lists to reports on early balloon ascensions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/22/ee2228f0-cb85-440a-b948-7a5bff8f4a08/balloon_1_.jpg)

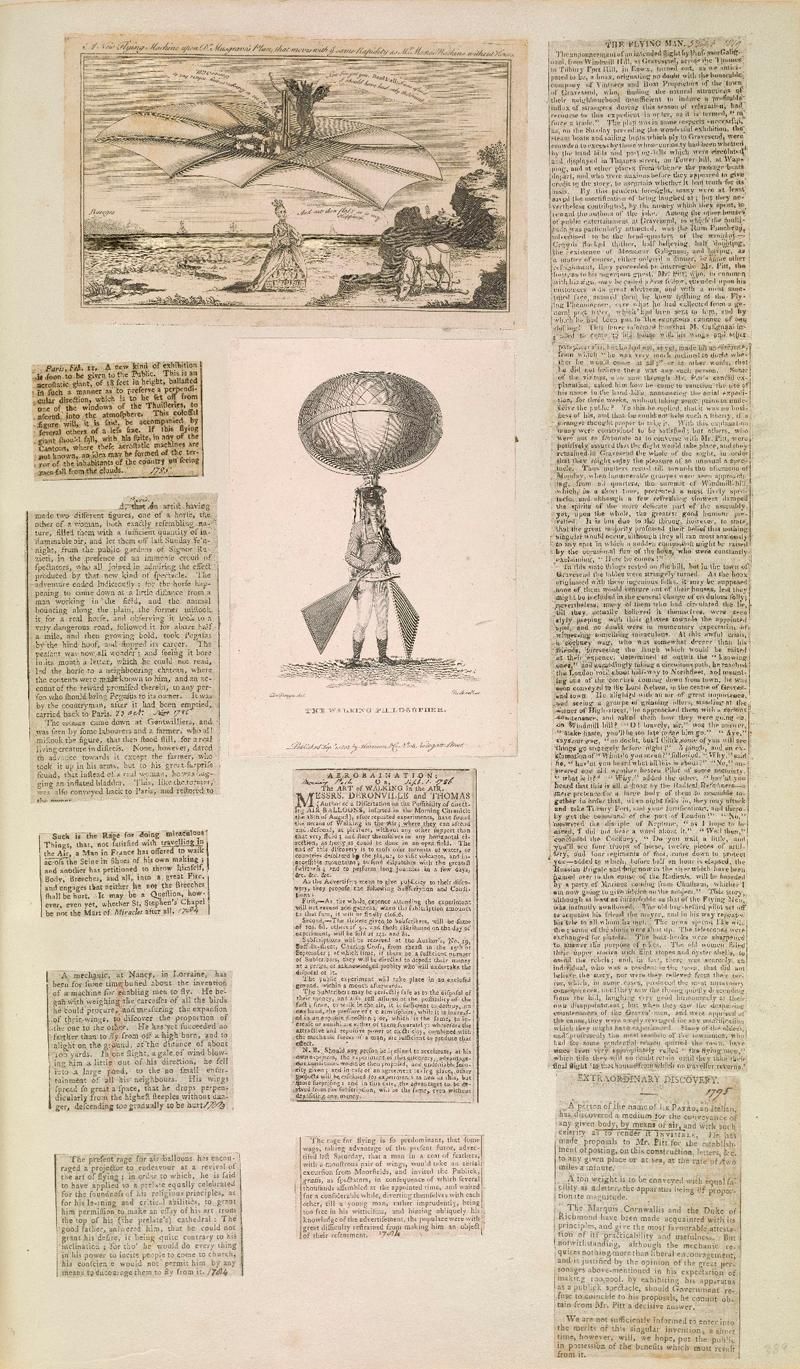

It was utter chaos. For two days in August 1802, immense crowds traveled from London to Greenwich in coaches, on horseback, and on foot hoping to see the aeronaut Francis Barrett ascend in his gas balloon. Those stuck on the roads set up telescopes in order to catch a glimpse of the balloon as it floated past. Gardens were trampled into dust, sheds collapsed when crowds climbed onto their roofs for a better view, and roaming gangs of pickpockets fleeced the crowds. When it became clear the balloon would not ascend (there was a hole in the fabric allowing the gas to escape as rapidly as it was put in), the spectators rioted, destroying everything they could get their hands on.

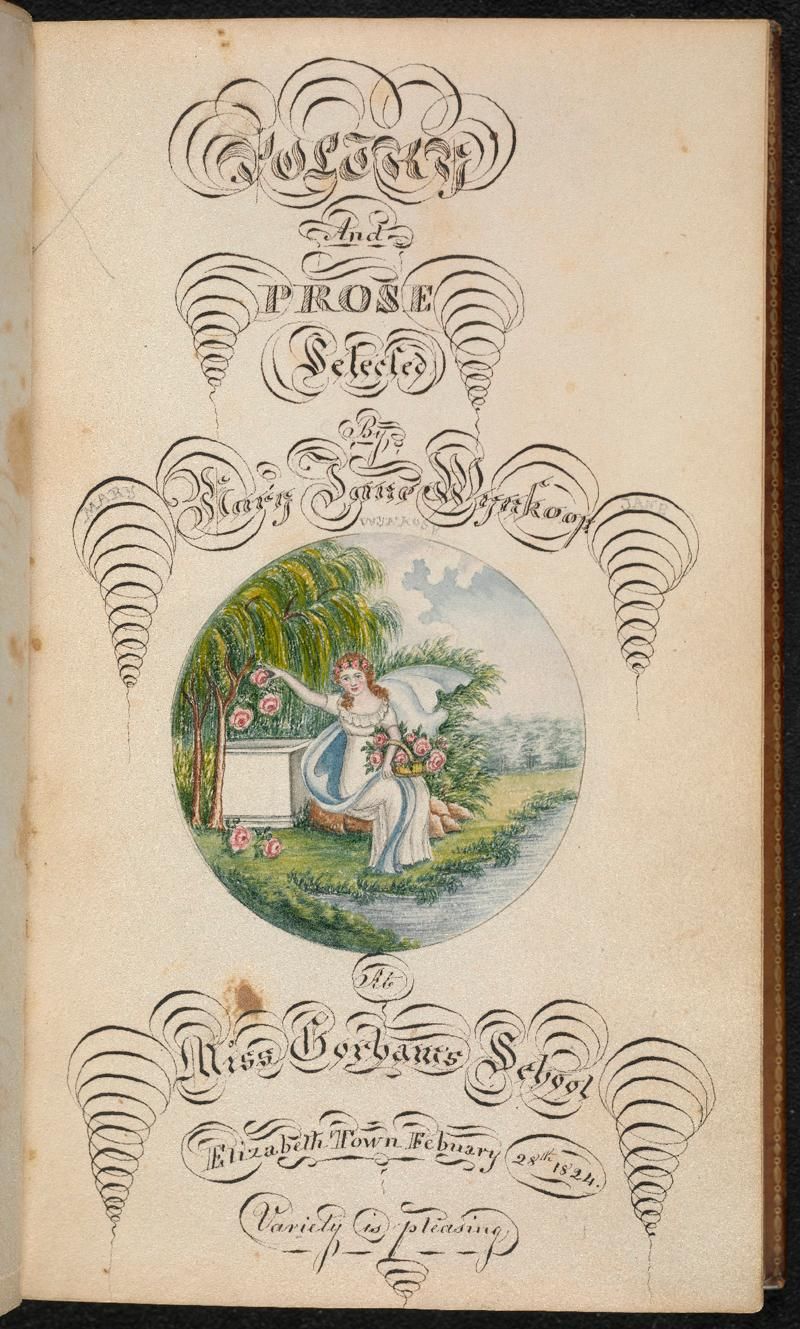

Barrett’s attempt is just one of dozens of such accounts found in a scrapbook of early aeronautica collected by librarian and bookseller William Upcott; the clippings, correspondence, and illustrations date from 1783 to 1840. When the Smithsonian Libraries placed a digital version of the unique scrapbook on the Smithsonian Transcription Center’s site, 87 volunteers logged on and quickly transcribed its 323 pages.

The transcription project was launched in 2014; although the Smithsonian has posted millions of digital images of items in the collections, many handwritten and typed documents aren’t word searchable. Volunteers register online, select a project, and start transcribing; when each page is completed, the work is reviewed by a second volunteer, and then verified by Smithsonian staff. In one popular project, volunteers transcribed more than 1,000 pages of the “as flown” Apollo stowage lists, which can now be sorted by object name, part number, or spacecraft.

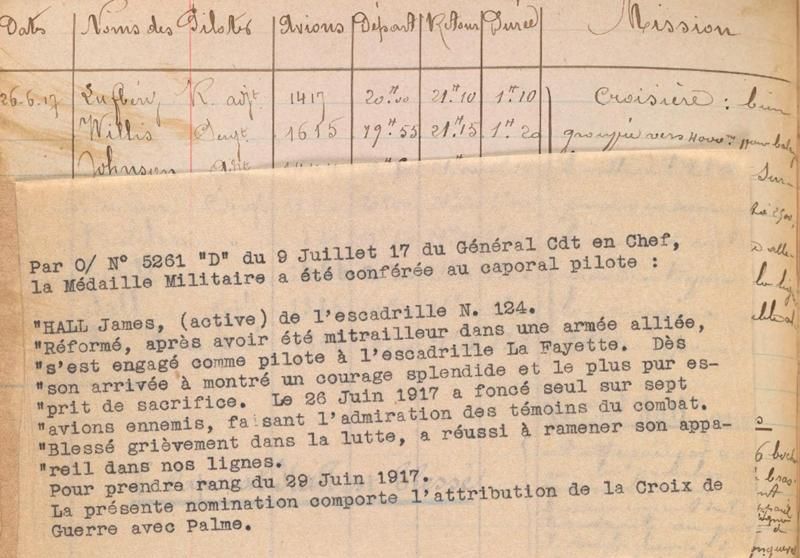

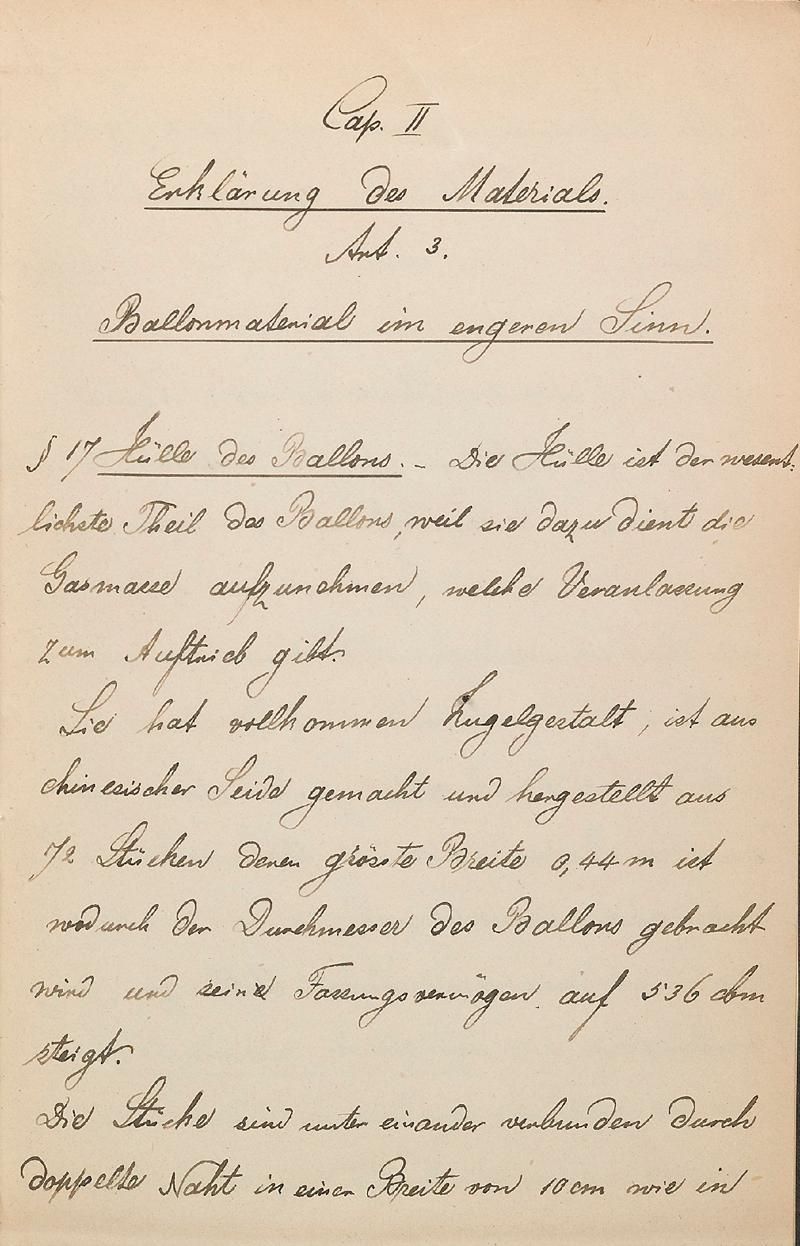

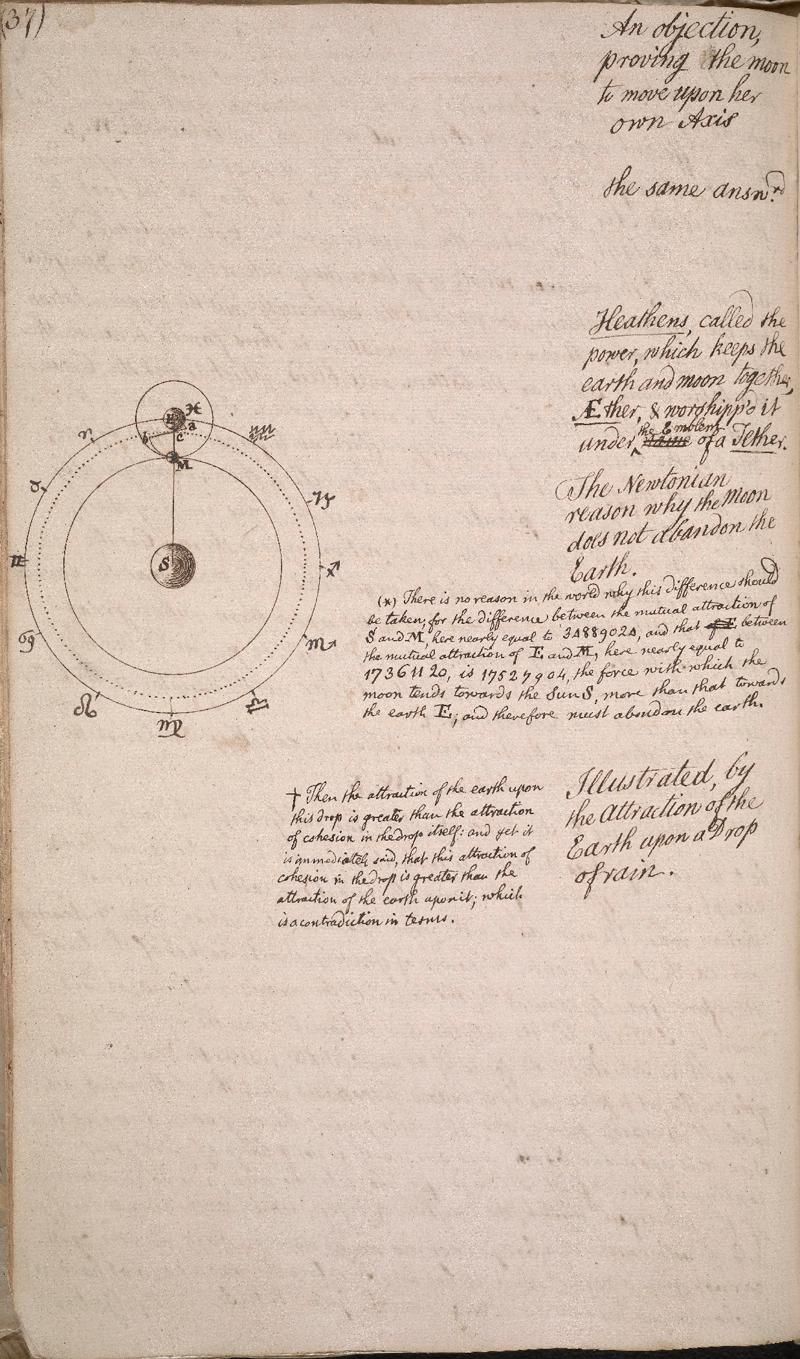

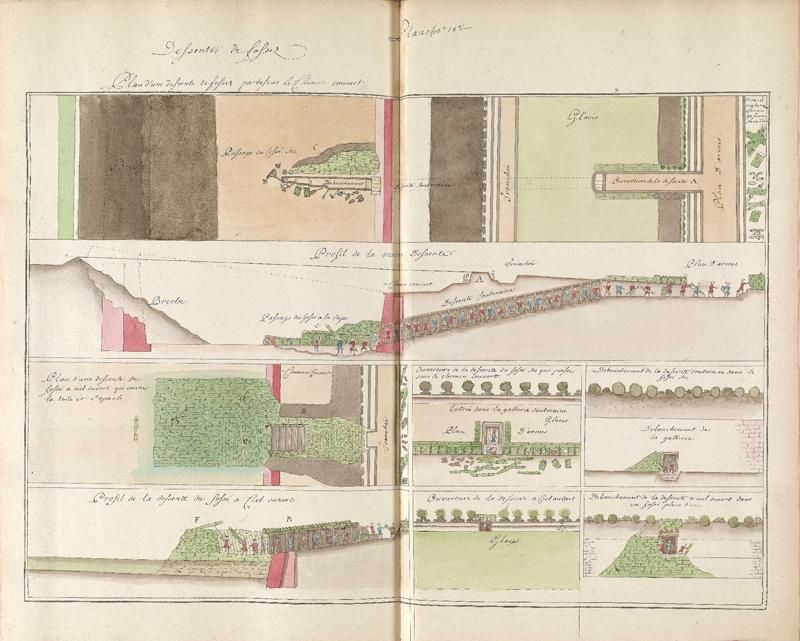

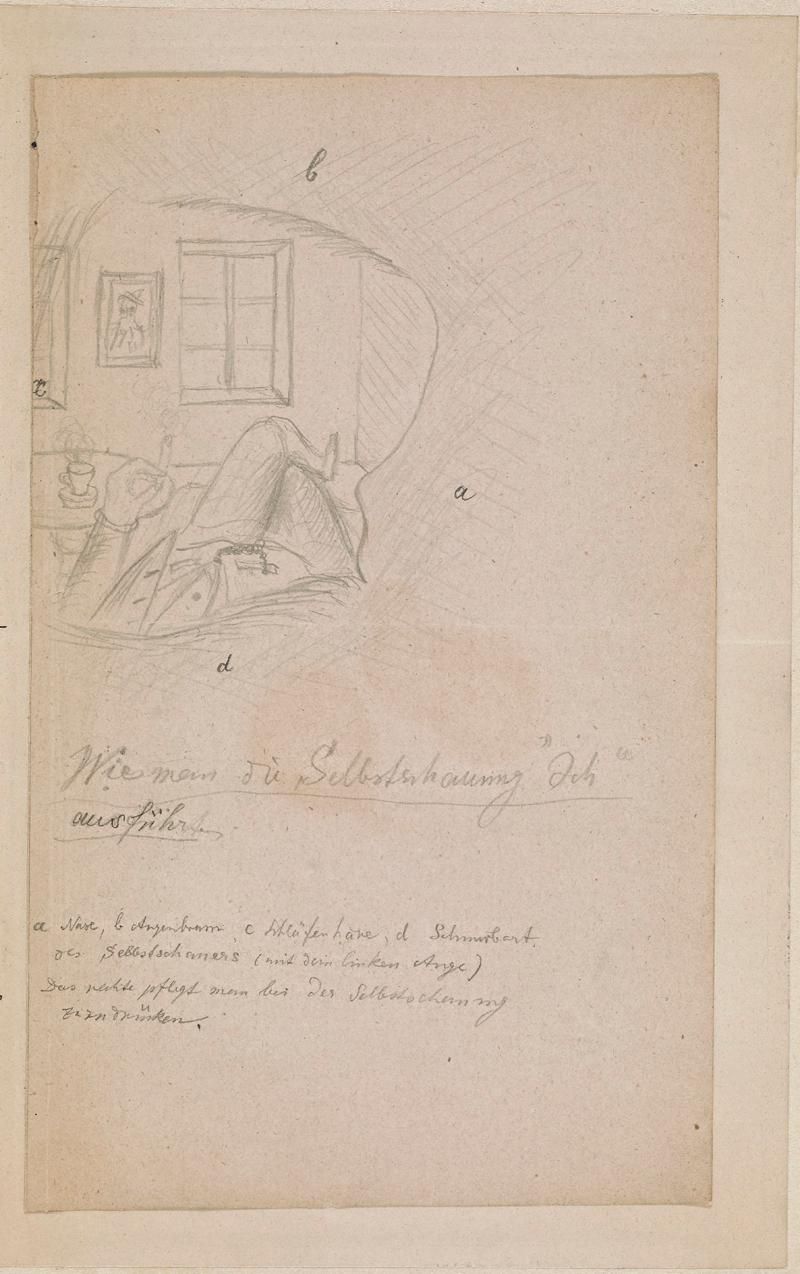

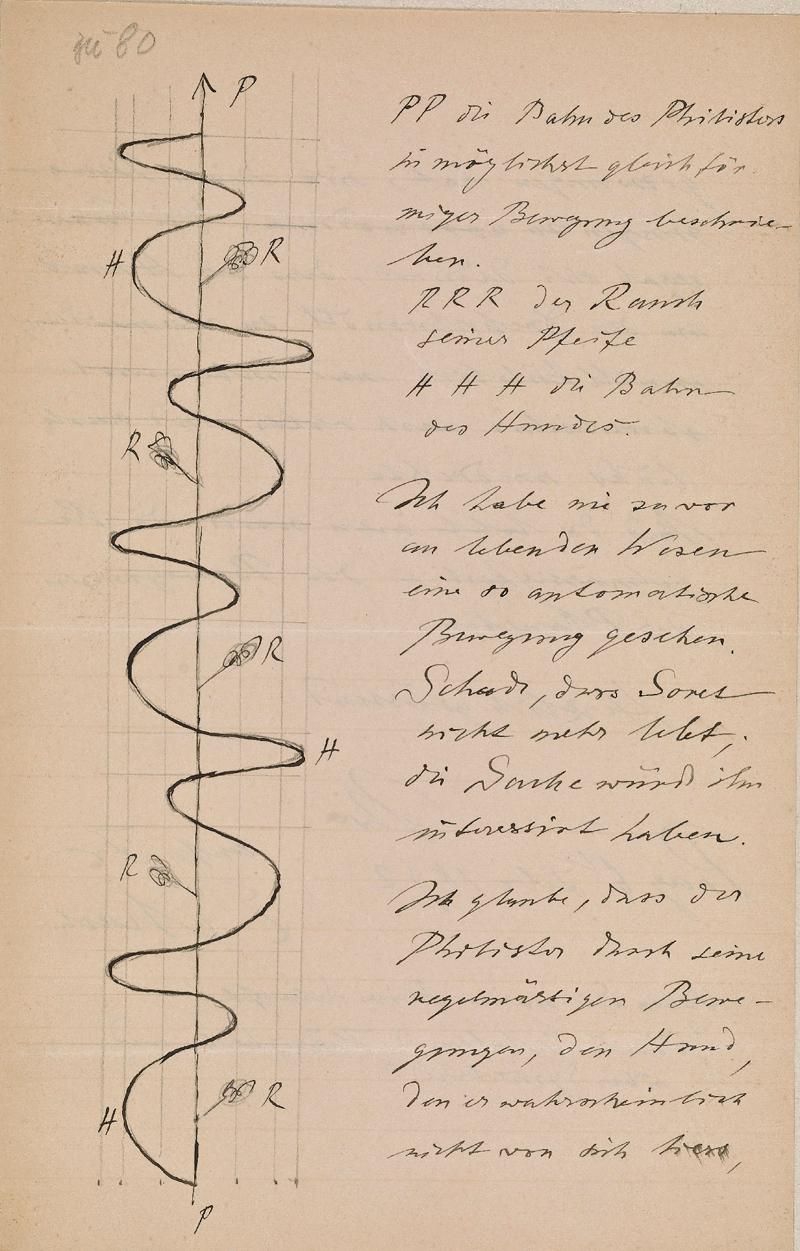

The Smithsonian Libraries has posted several projects with an aeronautical bent: the operations journal of Lafayette Escadrille Capitaine Georges Thenault; items from the Ernst Mach papers; a 19th-century German manuscript on the construction and use of military airships.

Transcription benefits the Smithsonian in several ways, says Smithsonian librarian Doug Dunlop. “It gets our materials out there, and we’re able to engage with the public, and they learn more about our materials. It also increases the accessibility of the materials; sometimes when researchers come into the library, they spend their time transcribing. If those materials are already transcribed, they can go online and download the pdfs. If they still need to come to the library, they can do that. It also helps that certain items—such as large, unwieldy scrapbooks—don’t have to be handled as much.”

View the slideshow to see various transcription projects posted by the Smithsonian Libraries.