Cuba During the Missile Crisis

Fifty years later, Cubans remember preparing to fight the Americans.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Cuba-Missile-Crisis-militiamen-1-flash-631.jpg)

On June 6, 1961, less than two months after the failed U.S.-backed invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, enormous wooden crates arrived at San Antonio de los Baños air base on the western part of the island, along with more than 100 Soviet troops. Inside the crates were MiG-15s and -19s, the first weapons in a buildup in Cuba that included Soviet fighters, bombers, radar, anti-aircraft batteries, and eventually the nuclear missiles that would ignite the 13-day standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union in October 1962. Today, 50 years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, Cubans recall how their government prepared them for what it insisted was the conflict’s inevitable end: all-out war with the United States.

A year after the MiGs arrived, Cuba’s armed forces chief, Raul Castro, younger brother of Cuban leader Fidel Castro, signed a secret agreement in Moscow allowing the Soviets to introduce offensive nuclear weapons to the island, just 90 miles from the Florida Keys. Not long afterward, truckloads of Soviet military equipment began flooding into Cuba.

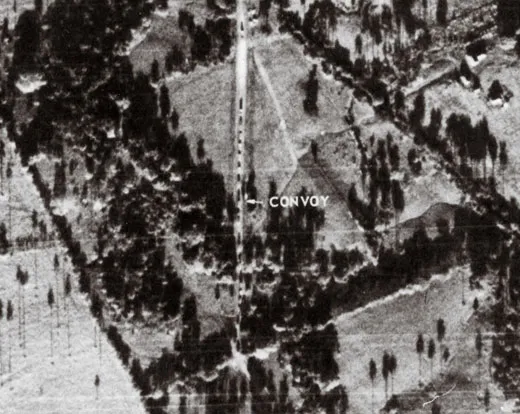

Miami resident Roberto Canas was a 13-year-old schoolboy living at the time near the small town of Moron. (He asked that his real name not be used since he travels regularly to Cuba to visit relatives.) Canas remembers playing in his front yard and seeing the convoys roll past. “We would see big trucks loaded down with all kinds of heavy equipment covered by large tarps traveling the roads around Moron,” he recalls. “We had no idea what was under those tarps. It was only because the trucks were under military guard that we knew that something important was being carried on them.”

For days, the mysterious trucks rumbled through the Cuban streets, highways, and countryside. Enormous 18-wheelers moved in convoys that stretched for hundreds of yards, cutting off traffic. Rumbling through rural villages and narrow paved roads, the convoys would sometimes pause while power lines and mailboxes along the route were removed to make room for their passage. Occasionally, a home, encroaching on the narrow road, was torn down. As the trucks passed through the various towns, they left a trail of downed telephone poles and crushed huts.

I had left Cuba, as a seven-year-old, two years before the missiles came, but I have heard many stories about what it was like on the island for the people who stayed. “Few, if any, Cubans really put two and two together,” Rafael del Pino writes me in an e-mail. Del Pino, a hero of the April 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion, had flown a Lockheed T-33 jet, shooting down two Douglas B-26 Invaders and sinking several CIA ships. “At that time, most Cubans listened to the government line that the U.S. wanted to invade the island. And after the Bay of Pigs, that was [believable]. The [propaganda] coming from our own government made us think we were going to be invaded by U.S. forces and the Soviet Union was defending us.”

Del Pino’s performance in 1961 set him on a course to become Castro’s chief air force adviser and, as such, a key eyewitness to the missile crisis. Today, at 74, the retired general is living in Europe under the U.S. Federal Witness Protection Program. One of the top-ranking defectors from the Cuban government, he fled Cuba in May 1987.

Del Pino recalls dozens of MiG-21F.13 fighters arriving at Santa Clara air base in central Cuba in August 1962, to be assembled by Soviet engineers. “When 44 aircraft were ready to fly, we knew something of great significance was up,” del Pino writes in Inside Castro’s Bunker, a memoir of his life in Cuba, published last July. “There were not enough pilots in Cuba, even including the ones with flight training in the Soviet Union, to complete the MiG-15 and MiG-19 squadrons we now had.” On September 15, about 50 Soviet pilots arrived at the base.

“Any lingering doubt as to what was about to happen disappeared in early October with the arrival of a squadron of Ilyushin Il-28 bombers at the San Julian air base, at Cuba’s extreme western tip,” del Pino recalls in his memoir. “This, plus the speedy installation of 24 SA-2 batteries in western regions and six in the eastern part of the island were unmistakable signals that war was near.”

Weeks before the missiles arrived that September, Soviet troops threw up cinder-block walls around parts of Cuba’s main harbor, Mariel, to shield it from view. Residents within a mile of the port were suddenly ordered to evacuate their homes. After that, all Cubans—even members of the Cuban military—were barred from Mariel, where the first missiles would come ashore.

It didn’t take long before word of the convoys, and the appearance in Havana of uniformed Soviet soldiers along with numerous young Soviet men in checkered cotton shirts and ill-fitting trousers, reached U.S. intelligence analysts. The stories streamed in from returning tourists, diplomats, and newspaper reporters, prompting the CIA in late August to step up its overflights of Cuba with the Lockheed U-2 spyplane. (The Air Force took over the flights two months later.)

“Cubans on the island noted the movement of trucks and materiel, tipping off American intelligence services,” says Brian Latell, a former Latin America specialist at the CIA and author of After Fidel: Raul Castro and the Future of Cuba’s Revolution. “But in the first few days, the missiles being described could not be proven to be offensive. Those reports of truck convoys…were critical to discovering the secret cargo. All human intelligence coming out of Cuba was checked and double-checked.”

In the early hours of Sunday, October 14, a U-2 Air Force pilot, Major Richard Heyser, took photos of the western part of the island. The next morning, fuzzy images of rural Cuba were unfolded on U.S. analysts’ light tables at the National Photographic Interpretation Center in Suitland, Maryland.

As photo interpreters scanned the images, several distinctive shapes caught their attention: 12 missile launch sites were detected near San Cristobal, 60 miles west of Havana, their presence kept secret even from the Cuban military. “The only Cubans on the island that knew of the missiles,” del Pino says, “were Fidel, his brother Raul, and [Argentinean-born confidant] Che Guevara.” The weapons were determined to be R-12 (NATO codename: SS-4) medium-range (600 to 1,000 miles) ballistic missiles. They could reach Washington, D.C., along with 40 percent of the Strategic Air Command’s bomber bases, in less than 20 minutes after being launched.

On Monday, October 22, President John F. Kennedy announced to a stunned world that he knew of the nuclear threat in Cuba. In a radio and TV address to the American people, Kennedy ordered a “quarantine” of the island (his word, since imposing a blockade would be considered an act of war) to intercept any Soviet ships carrying more missiles. The reaction on both sides was immediate.

“American kids on the U.S. side of the crisis were practicing duck-and-cover drills, and their parents were building bomb shelters in the back yards. But the kids in Cuba were joining the communist Young Pioneers and chanting slogans and waving fists in the air, ‘Down with Yanquis!’ ” says Miami resident Diego Gonzales. (He also asked that his real name not be used because he fears for family members still in Cuba.) Gonzales had just earned a business degree at the University of Havana and was living with his parents in Havana.

“Cuban kids never did cover drills for bombing because the secrecy maintained by Castro’s government about the situation kept the people from knowing what was going on,” he says. “The kids wore their brand-new Young Pioneers’ uniforms. We were told the Yanquis were invading us and that the Russians were protecting us. When we discovered [after Kennedy’s address] that Fidel had allowed Russian missiles on the island, we thought that was the end of the story. We would be invaded by the Americans for sure, or we would all die in a huge nuclear blast.”

One of the iconic phrases that sprang up all over Cuba in the days after the Bay of Pigs—on walls, sidewalks, sides of buses, anywhere there was space to write—was Patria o muerte; venceremos: “Fatherland or death; we will prevail.” This call to action reminded the island’s six million people of the showdown’s seriousness. (Fifty years later, the graffiti still adorns Cuban walls and buildings.)

Even as the Cubans prepared to fight the invaders, they feared and mistrusted one another, says historian Jaime Suchlicki, director of the Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies at the University of Miami. Castro had strengthened the police-state he imposed after the Bay of Pigs. Anyone suspected of being a “counter-revolutionary” faced prison or the firing squad, and people were encouraged to report their suspicions about counter-revolutionary activities. The missile crisis “was a period of heightened tension for the government and for the Cuban people,” says Suchlicki. “The regime was scared that their hard-won revolution might be stolen back by the Americans. It was a time everyone was on edge.”

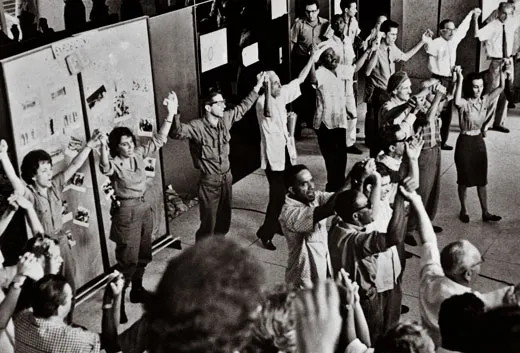

By October 25, Cuban men and women of all ages and professions were taking their place in people’s defense units—civilian “militias” organized by the Cuban military to counter the perceived U.S. threat. These were unarmed civil defense units, and included brigades for health and sanitation, firefighting, and construction. But they were loosely organized; only the firefighters and medical emergency responders conducted drills.

“All over the island, fed by Fidel’s fiery speeches, people were getting ready to fight,” recalls Canas. “We were a small island. The United States was our enemy. Everybody was yelling Patria o muerte! It was crazy. Fidel is up there telling everyone the Yanquis are coming back to finish the job. Everyone was joining defense brigades, even grandmothers.”

Fidel’s anti-American speeches during the crisis were epic, says Suchlicki. “They lasted sometimes six, seven, eight hours and were broadcast on every channel and every radio station. The speeches railed against the United States, and warned of a Yanqui attack at any moment. The Cubans did not realize the danger they were in; it all happened too quickly. People may have seen trucks covered in tarps, or maybe low-flying planes, but they had no idea what was under those tarps or what those planes were looking at. I think most Cubans on the ground at that time knew that they were heading toward a conflict with America.”

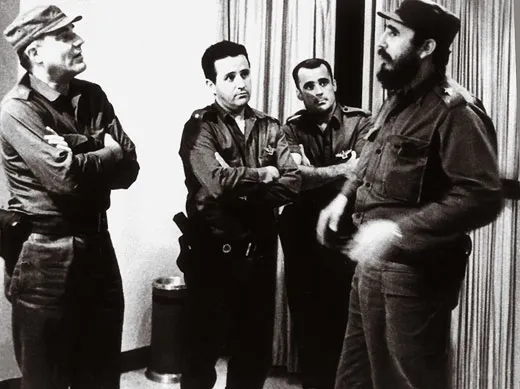

The Cuban government ordered all armed forces units to be ready for combat. Del Pino was told to report to a secret command post at armed forces headquarters on the outskirts of Havana, where Castro urgently needed an air force adviser.

“We were to go to one of the various tunnels under construction along the banks of the Almendares River,” he writes in Inside Castro’s Bunker. “This particular tunnel was not yet finished, but offered protection against the air attacks we were anticipating.” The tunnel was about 13 feet wide, 20 feet high, and 500 feet long. Every 100 feet, on either side, were 32- by 98-feet-deep chambers serving as work stations for various government officials. “The tunnel was strong enough to withstand a nuclear attack, but the engineers had failed to provide any ventilation system, and the resultant lack of oxygen and high humidity was almost intolerable. Nevertheless, with the imminent threat of war, the high command felt this was the safest and most reasonable place for the main command post,” del Pino writes.

On October 25, with the United Nations attempting to resolve the crisis, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev sent a coded message to Kennedy through the Soviet Embassy in Washington proposing to withdraw the missiles in exchange for an end to the naval blockade, and a guarantee that the U.S. would not attack Cuba. That evening, according to del Pino, Castro arrived at the riverside bunker, read the command post reports, and grew livid when he learned the Soviets were negotiating with the Americans behind his back. He called for his Soviet advisers and shouted at them that he was ordering all Cuban military units to fire on any U.S. aircraft in Cuban airspace.

Castro paced back and forth, rolling his cigar between thumb and fingers, del Pino writes. “Then he fixed his gaze on me and, with the cigar still between his fingers, pointed at me asking, ‘What chance do our MiG-15s and MiG-19s have of shooting down the Yanquis’ F-101s and the other planes that make daily reconnaissance flights?’ ”

Del Pino answered that the chances were not very good. He pointed out that the Cuban pilots had no radar and would be able to engage only if they were lucky enough to chance upon a visual sighting of an enemy aircraft. Under the circumstances, he told his president, he was not hopeful of shooting down U.S. aircraft. Castro was undeterred; he wanted both “anti-aircraft artillery and the pilots to open fire on any Yanqui planes they spot!” (The Cubans scrambled only once during the crisis, when a MiG-19 was sent up after an Air Force RF-101 Voodoo, but the MiG didn’t have air-to-air guided missiles.)

At 5:45 a.m. on October 26, del Pino sent a coded message to the air bases at San Antonio de los Baños, Santa Clara, and Holguin: “Fire on the Indians.”

Later that day, Khrushchev sent Kennedy another secret letter, this time delivered by Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin to the president’s brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy. It called for the United States to also withdraw its Jupiter missiles from Turkey in exchange for removal of the missiles in Cuba. President Kennedy, Dobrynin was told, was anxious to get rid of the already obsolete Jupiters, and had ordered their removal some time ago. But since those missiles were installed under the auspices of NATO, it would be difficult for the United States to unilaterally remove them without damaging the structure of the alliance, the younger Kennedy said.

The next morning, October 27, an unarmed U-2F piloted by 35-year-old Air Force Major Rudolf Anderson Jr. took off from McCoy Air Force Base in central Florida and headed for Cuba. On station at 70,000 feet, he could see the curvature of Earth. On the ground stood batteries of Soviet surface-to-air missiles. At noon, three SA-2 anti-aircraft missiles nestled in the tropical foliage of Banés were launched toward Anderson’s airplane; two hit it, killing him.

“Much speculation has surrounded this U-2 incident,” del Pino says. “It has even been said that the missile unit had been taken over by Cubans and that the Cubans had opened fire on the U-2. This is sheer fantasy. Anyone who is knowledgeable in the complexities of these missile systems can understand that it takes at least two years of learning and training for an officer to be capable of operating them with minimum efficiency. At the time of the missile crisis, we didn’t have the slightest idea of the operating principles of an anti-aircraft missile.”

Almost four hours after the U-2 was hit, several U.S. Navy RF-8A Crusader aircraft flying low-level photo-reconnaissance missions over Cuba were also fired on. One was hit by a 37-mm shell but managed to return to base in Key West, Florida. Miami resident Eriberto Diaz, now 82, lived in the Ciego de Avila region of Cuba and remembers such flights: “One or two American observation planes flew very low near our house. My mother and I could hear them but did not see them. Later, I heard that one of the American planes had been shot down. I thought, This can’t be good.”

At 4 p.m. the day of the U-2 shootdown, Kennedy urgently summoned his advisers to the White House. A message was sent to U.N. Secretary General U Thant asking the Soviets to suspend work on the missiles while negotiations were carried out. During Kennedy’s meeting, Army General Maxwell Taylor, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, delivered the news about Anderson and the U-2. Though his advisers urged him to retaliate against Cuba or at least allow U.S. pilots to return fire if attacked, the president resisted.

Late on October 27, Kennedy agreed to a dual strategy: a formal letter to Khrushchev accepting the non-invasion pledge, along with a secret agreement that Washington would remove the Jupiter missiles in Turkey and southern Italy if the Soviets removed their missiles from Cuba. If that secrecy were breached, the American public and NATO allies would see the deal as a concession to blackmail. Though the crisis was over, the full terms of the agreement would not become publicly known until years later.

Whose idea was it to put the missiles in Cuba? Historian and Kennedy adviser Arthur Schlesinger told National Public Radio in October 2002 that he believed Castro did not want the missiles, but that Khrushchev pressured him to take them. Khrushchev seemed to back that up in his memoirs, the first volume of which was published in 1970: “It would have been ridiculous for us to go to war over Cuba—for a country 12,000 miles away. For us, war was unthinkable. We ended up getting what we’d wanted all along: security for Fidel Castro’s regime and American missiles removed from Turkey.”

Crucial to the peaceful resolution of the crisis was that the missiles in Cuba were always under Soviet control. Castro, Khrushchev writes, “was hot-headed” and had pleaded for Moscow to launch a pre-emptive nuclear strike. Castro’s second-in-command, Che Guevara, told the London Daily Worker in November 1962 that had Castro gained control of the missiles, “We would have used them against the very heart of the U.S., including New York.”

In the Cuban-Soviet relationship, the Soviets clearly had the upper hand, says Suchlicki. “The Soviets used Fidel, plain and simple,” he says. “If they had wanted to protect Fidel, they would have made him part of the Warsaw Pact and made the island a protectorate. No, the Soviets brought missiles to Cuba to barter with the U.S., to make the Soviet Union as powerful and influential as the U.S., and to redress the balance of nuclear power.”

But del Pino is certain the missiles were Castro’s idea. “The truth is that Castro proposed the idea to Khrushchev, who, in accepting the offer, fell into the Cuban dictator’s trap,” he says. Both the Bay of Pigs victory and the missile crisis “had paved the way for Fidel to fight the war he had always wanted to wage against the United States, a war that would assure him a place in history.”

Though that war did not come, the crisis led to significant actions on both sides. Washington and Moscow set up the Hotline Agreement, establishing a direct means of communication between the White House and the Kremlin. The body of Anderson, who posthumously became the first recipient of the new Air Force Cross medal, was returned to the United States and buried in November 1962 with full honors in Greenville, South Carolina.

For many Cubans, the crisis marked a turning point in their lives. “I remember looking at the palm trees and the sky and thinking, It is all still here. Havana didn’t go up like a bonfire,” Gonzales says. “It was right there and then that I decided I was leaving Cuba.” He left within a few months.

Rafael Lima is a communications professor at the University of Miami.