The Czech Fighter That Helped Israel Win Its War of Independence

Battling for Israel, volunteers fought in an aircraft that should have been grounded.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/b7/81b7dc4c-cbac-4480-b438-30cd088f58fb/12d_sep2019_6101squadronpilotswithczechknife_live.jpg)

No one loved the Avia S-199 at first sight. Perched on narrow, splayed-out landing gear, the Czech-built fighter had a sinister look that made pilots and potential buyers wary. And when airmen became better acquainted with the long-snouted warplane, the wariness turned to distrust.

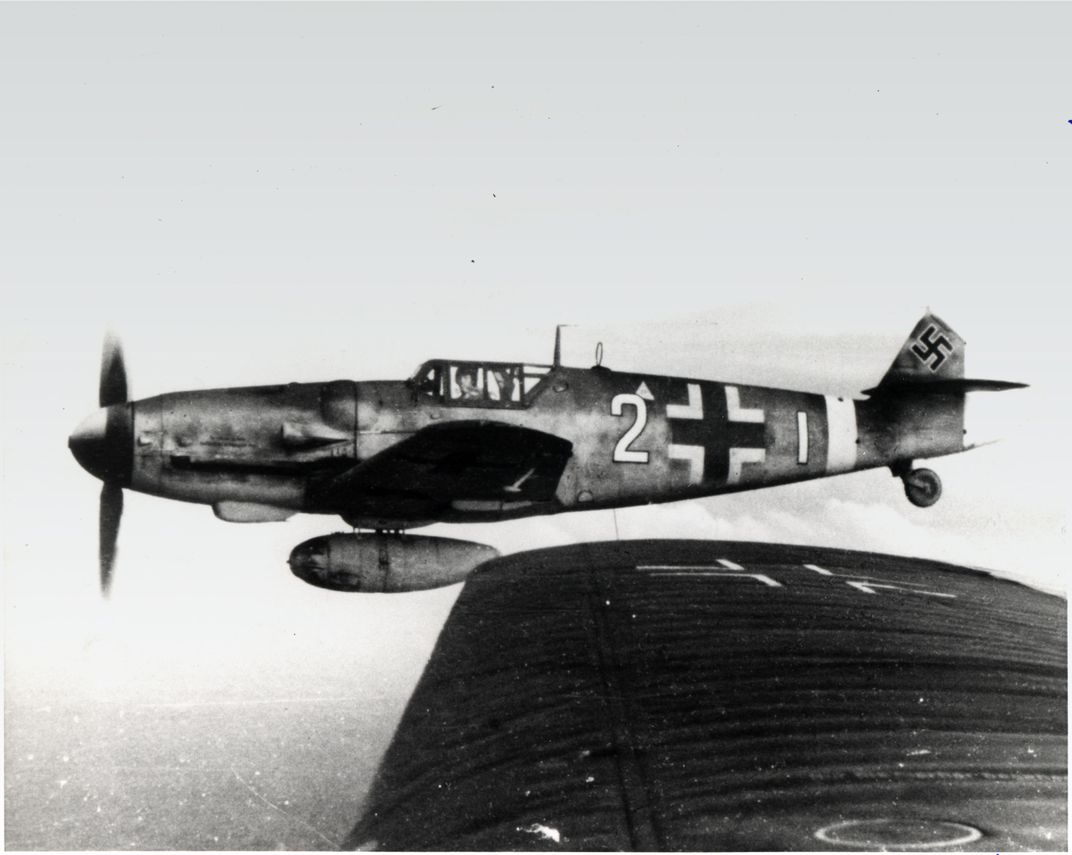

The single-engine S-199 was a product of the Avia Company in Czechoslovakia, which had tooled up to produce Messerschmitt Bf 109s for the German Luftwaffe just as World War II ended. After the war, the company opted to manufacture a version of the Messerschmitt fighter for the Czech air force.

The Daimler-Benz DB 605 V-12 engine, which had propelled the Bf 109, was no longer available, so Avia installed the heavier but less powerful Junkers Jumo 211F, the same engine used in the Luftwaffe’s versatile Heinkel He 111H medium bomber. To match the Jumo engine, Avia mounted the Heinkel’s massive oar-shape propeller, which would turn out to be a dangerous combination for the small airframe of the S-199. For the clunky fighter, Avia, not surprisingly, found no buyers other than the Czech air force.

But in the spring of 1948 another customer appeared. The nascent state of Israel was poised to declare its independence. Looming on Israel’s borders were the armies of five surrounding Arab countries, ready to invade the new nation. Israel urgently needed weapons, armor, munitions, and, especially, military aircraft. Neither of the world’s two largest owners of surplus war assets—the United States or Great Britain—was sympathetic. The U.S. Department of State strictly enforced the Neutrality Act, which banned the sale and shipment of war materials to countries engaged in armed conflict, such as Israel. Britain’s government was even less friendly, not only imposing an embargo on arms to Israel but also supplying aircraft and training to the Arab air forces.

Israel was desperate. Although volunteer airmen had smuggled a handful of surplus transports and training aircraft past the embargo enforcers, they had failed to score any fighters. Israel turned to cash-strapped Czechoslovakia, which was selling arms on the international market. In secret talks, the Czechs let it be known they would sell 25 Avia S-199 fighters to Israel.

No one representing Israel liked the deal—or the ersatz Messerschmitt. The price was outrageous: $180,000 for each fighter, including weaponry, pilot training, and support equipment. Meanwhile, the superior North American P-51 Mustang was selling in the United States for a mere $4,000. But the Mustang—and every other modern fighter—was off limits. Israel’s de facto head of state, David Ben-Gurion, personally gave the order: Buy the Czech fighters. Send pilots to learn to fly them—now.

The first band of volunteers—two Americans, one South African, seven native Israelis—arrived at České Budějovice air base on May 11, 1948. Lou Lenart, a wiry former U.S. Marine Corps pilot, made the group’s first flight in the S-199. It was nearly his last. Recalled Lenart in The Lion’s Gate, a book published in 2014: “The big paddle-bladed propeller produced so much left-pulling torque, that the first time I tried to take off, the plane ran away from me clear off the runway, through a fence, and over a cliff.” Lenart fought to keep control while the fighter grudgingly gained enough speed to fly. When he landed back at the airfield, the pilot noticed his fellow volunteers staring at him. They were amazed he was alive.

Lenart’s inaugural flight was the beginning of a turbulent relationship. To the volunteer pilots, the Czech fighter seemed to have a vicious streak, like an attack dog turning on its handler. The narrow landing gear made the S-199 difficult to keep aligned during takeoff. Directional control was made even worse by the enormous torque of the propeller. The Czechs called the S-199 mezec, meaning “mule.” The Israeli air force gave the fighter a more menacing name: messer, Yiddish for “knife.”

The volunteers had barely begun training when, on May 15, the radio in their Czech quarters broadcast the news that Israel’s war of survival had begun. “We heard that Tel Aviv had been bombed from the air,” remembered Ezer Weizman in the 1976 book On Eagles’ Wings. Weizman, who would later command the Israeli air force and eventually be elected president of Israel, recalled the airmen’s reaction to the broadcast: “ ‘That’s enough,’ we proclaimed. ‘We’re going home.’ ”

While training in Czechoslovakia, only five of the volunteers, those with World War II experience, had qualified in the tricky fighter, and none had flown it more than a few times. The first few S-199s were disassembled and loaded into transports and flown by night to Ekron airfield in Israel.

The war was going badly for Israel. By the evening of May 29, the Egyptian army had advanced northward along the Mediterranean coast to the village of Ashdod, 20 miles from Tel Aviv. Israeli commandos had blown up a bridge, halting the Egyptian forces. By next morning, however, the bridge would be repaired and the Egyptians would be in the city.

The existence of the Czech-built fighters at the Ekron airfield was a closely held secret. The newly assembled S-199s had not been test flown. The guns had never been fired. None of the radios worked. But if the Egyptian army was not stopped, none of these concerns would matter.

Four S-199 pilots took off an hour before dark. Lenart, who led the four-ship flight, had never flown in Israel before. Where was Ashdod? he wondered. All the villages along the coast looked alike. Seconds later, it became stunningly clear. A column of enemy trucks and armor stretched for more than a mile south of the bridge at Ashdod.

“We started coming down, and right away the whole place erupted,” said Lenart to Leonard Slater, author of The Pledge, a book published in 1970. One after the other, the pilots dove on the enemy column. Each dropped his pair of bombs, then swept back down to strafe. After only a few rounds, though, the wing-mounted cannon on each fighter jammed.

The mission ended in calamity. The number four S-199, flown by South African Eddie Cohen, was shot down in flames. Israeli pilot Mordechai “Modi” Alon, flying the number two aircraft, swerved off the runway at Ekron in what would be the first of many S-199 gear-demolishing ground loops.

Darkness fell, and a mood of despair swept over the little band of airmen. They had inflicted little real damage on the enemy, leading them to question the value of their efforts. An hour later, they had an answer. Israeli monitors had intercepted a radio message from the Egyptian commander at Ashdod. Stunned by the appearance of Israeli fighters, the Egyptians were halting their advance. Tel Aviv had been saved—for the moment.

At dawn the next day, the two remaining S-199s, flown by Weizman and American volunteer Milt Rubenfeld, attacked a Jordanian-Iraqi armored column in the north of Israel. Rubenfeld’s fighter was hit by ground fire. He barely made it to the Mediterranean shore before bailing out at low altitude. Though seriously injured, he survived.

It was an inauspicious debut for the Czech Knife. In the first two missions, two fighters had been lost and one severely damaged. Of the first five pilots, one was dead and another too injured to fly again. But the secret was out: Israel had an air force. To make it official, the unit was given a designation: 101 Squadron, a grand-sounding label for a ragtag outfit down to one flyable airplane and three pilots.

A few evenings later, the Czech Knife rose to glory. Flying the lone remaining S-199, Modi Alon intercepted a pair of Egyptian bombers over downtown Tel Aviv. In view of thousands of astonished Israelis, Alon blew one bomber out of the sky, then the second. He instantly became a hero, and the 101 Squadron’s new commander.

But Alon’s targets had been slow-moving C-47 transports configured as bombers, easy prey for any kind of fighter. How, wondered both Israeli and Arab pilots, would the Czech Knife fare against a real fighter, like the British-built Supermarine Spitfire?

The answer came a few days later. On his first mission in the S-199, newly arrived volunteer Gideon Lichtman engaged a flight of Egyptian Spitfires. “I had a total of 35 minutes in the Messerschmitt,” Lichtman told me during an interview in November 2015. “I couldn’t find the switch to arm the guns.” Frustrated, Lichtman kept flipping switches until he found the right one. Tailing in behind one of the Spitfires, he opened fire. “I saw pieces coming off the Spit, then smoke, and he went down in the desert,” said Lichtman.

More kills followed. Alon added to his tally, downing another Spitfire. So did World War II pilot Rudy Augarten, who, while flying a P-47, had destroyed two German Bf 109s over France. Other pilots began to score victories.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/b3/50b341cc-c351-4bf0-ae15-107bfb6bc0f7/12f_sep2019_5israelsfirstacerudyaugarten_live.jpg)

The Knife was proving to be a potent fighter—once it was in the air. Its behavior on the ground was another matter; it still had a tendency to careen off the runway on both takeoff and landing. When the 101 Squadron moved from the concrete runways of Ekron to a newly bulldozed strip at Herzliya in June, the pilots hoped the Knife would behave better. It didn’t. Accidents were so frequent that ground crews assembled a set of long poles to flip upturned fighters right side up.

Not surprisingly, the S-199s were difficult to maintain, and Israeli mechanics labored in the summer heat to keep them flying. “They were never able to get more than four planes in the air,” recalled volunteer Mitchell Flint, whom I interviewed on July 9, 2015.

When the Israelis complained about the S-199’s miserable record, the Czechs blamed the crashes on the pilots’ lack of experience with the type. Their claim had some validity since the volunteers had received only minimal training in Czechoslovakia before being rushed to the harsh environment of the Middle East. Pilots accustomed to the wide-track landing gear of American fighters—P-47s, P-51s, F4Us—were unprepared for the quirky Messerschmitt undercarriage.

The Czech Knife didn’t reveal its deadliest trait until the morning of July 9. Lenart was assigned to lead a four-ship raid on the Egyptian air base at El Arish. The mission got off to a rough start when his number two pilot, Californian Stan Andrews, swerved on takeoff, flipped upside down, then blocked the runway for 15 minutes. Down to three fighters and short on fuel, Lenart opted to strike a closer target, the Egyptian-held seaport at Gaza.

Only two S-199s made it back. The third, flown by another young Californian, Bob Vickman, had vanished. Searchers and radio monitors tried all night but failed to learn the fate of Vickman.

The next day, it happened again. A pair of S-199s jumped two Syrian dive bombers near the sea of Galilee. The lead pilot, Battle of Britain veteran Maury Mann, made short work of the first bomber, shooting it down in a matter of seconds. Mann’s wingman, South African Lionel Bloch, swung in behind the second, chasing him northward toward Syria. That was Mann’s last glimpse of Bloch. A second S-199 had vanished.

The following morning, a South African ex-medical student named Syd Cohen jumped in an S-199 and went looking for his lost countryman. Acting on a hunch, he gave the trigger for his nose-mounted machine guns a short squeeze. He felt the rattle of the two guns—and then something else, a different vibration.

Back on the ground, Cohen’s suspicion was confirmed. All three propeller blades had bullet holes in them. The synchronizer enabling the guns to fire between the blades was flawed. Vickman and Bloch had probably shot off their own propellers.

In October, Israel launched Operation Yoav, an offensive in the Negev desert. Every flyable S-199 was put to use. Alon had returned from a bombing and strafing mission on the coast. In the landing pattern at Herzliya, Alon reported by radio that he had a landing gear problem. That was another S-199 quirk, one or both main gear failing to extend. The remedy was to yank the fighter’s nose up and down to coax the gear out of its well in the wing.

While Alon was sorting out his problem, observers on the ground spotted something more troubling. A trail of gray smoke was streaming from the fighter’s nose. The controller in the makeshift tower radioed for Alon to check his temperatures. They were okay, Alon replied. It was his last transmission. Seconds later, Alon’s fighter nosed down and crashed in flames beside the runway.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b9/0e/b90e57fc-6f3c-426f-8716-861a592abfa4/12g_sep2019_3bengurionvisits101squadron_live.jpg)

That evening the pilots huddled at their makeshift bar and talked about what happened. Alon had become a near-mythical hero in Israel, the charismatic young David who had taken on the Arab Goliath. “Everybody in the squadron was crying,” remembered Augarten in No Margin for Error. “In all the wars I’ve been in, I had never seen anything like that.”

No clear cause for Alon’s crash was determined. There was no time to grieve. The war was reaching a climax. Despite the ongoing embargo, more warplanes were joining the Israeli air force, including three Boeing B-17 bombers smuggled from the United States, four Bristol Beaufighter strike aircraft from Britain, and a pair of disassembled U.S. P-51s in crates marked “farm equipment.” Best of all for the 101 Squadron pilots, Czechoslovakia was providing Israel with World War II-surplus Spitfires.

With its augmented air force, Israel took command of the sky. By the last day of air combat, January 7, 1949, the Spitfires had shot down 15 hostile aircraft. The P-51s destroyed four. And the S-199s, despite their calamitous history, accounted for seven air-to-air kills.

For all its treacherous attributes, the Avia S-199 had played a critical role in Israel’s formation. The mere sight of the fighter in the early days of the war had terrified the invaders and roused the spirits of the outnumbered defenders. “It was all we had,” said Gideon Lichtman. “So we flew it. And we stopped the enemy.”

Without the S-199, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War might have had a different ending.